Update Oct. 11:

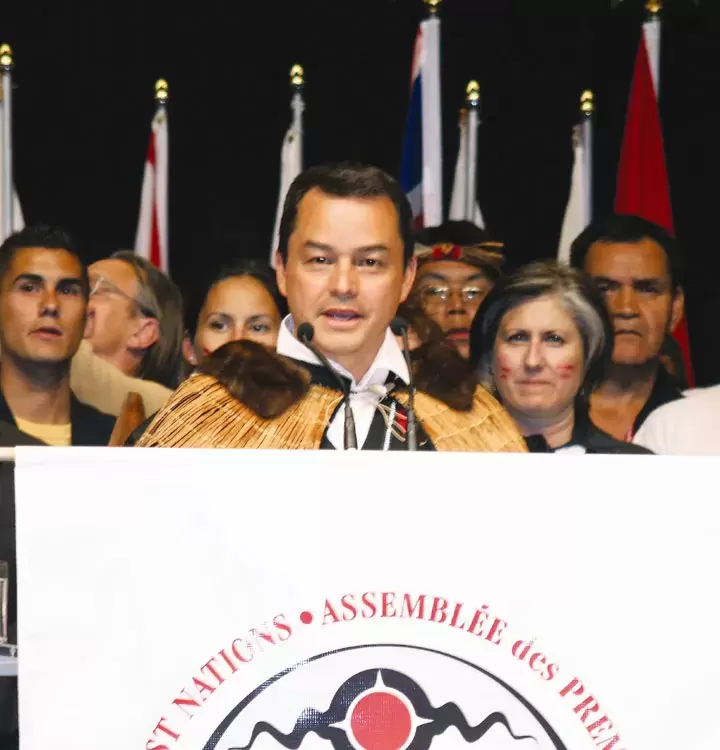

Assembly of First Nations (AFN) National Chief Shawn A-in-chut Atleo announced today the Assembly of First Nations will withdraw from the British Columbia Missing Women’s Commission of Inquiry, citing limitations of the Inquiry itself and an imbalance and inequity in legal resources made available to the parties.

“The Assembly of First Nations is no longer confident the Inquiry will bring justice for the families of missing and murdered women in Canada,” said Atleo, adding that the national First Nation advocacy organization has exhausted every option and appealed for cooperation and conciliation between the parties to better ensure a united and common purpose in finding truth and answers for the families.

“The principle objectives behind AFN’s participation from the beginning have been to support the families, to bring to light systemic issues that gave rise to these tragedies and finally to identify efforts toward resolution of those issues,” said the National Chief. “We hoped the Inquiry would shed light to uncover truths that could help with the healing process for the families as well as to begin to point the way forward so that all women and the most vulnerable have access to justice. Without equity and balance, systemic issues will not be brought forward and will therefore not be reflected in the recommendations of the Inquiry.”

In a joint letter with other parties to the Inquiry, the AFN appealed to the British Columbia Premier, as recently as on Sept. 28, as a last effort requesting a meeting of all parties to salvage a way forward. The B.C. Attorney General sent an unequivocal response indicating that such a meeting would not be convened. The AFN continues to urge the government of British Columbia and the Commission of Inquiry to find remedy and ensure that justice is served.

“The families of the many murdered and missing women fought for this Inquiry as an essential vehicle to uncover the truth behind their personal tragedies,” said Jody Wilson-Raybould, AFN Regional Chief for British Columbia. “The current uneven configuration of the Inquiry seriously limits, if not eliminates, the potential of the Inquiry to achieve this most basic interest.”

Ending violence against Indigenous women is a key priority for the AFN and First Nations across Canada consider the reality of missing and murdered Indigenous a national tragedy that requires immediate attention by all levels of government. First Nation chiefs across Canada are working to raise awareness of this issue and have passed a number of resolutions supporting action to ensure the safety of Indigenous women across Canada and support for the families of missing and murdered Indigenous women.

“The AFN will continue to press for justice and will re-double our efforts to bring focus, attention and, most importantly, action to this issue,” said Atleo. “We will press for action and commitment from all levels of government. First Nations resolved by consensus to press for a national level inquiry and we will continue this struggle for justice through other avenues including through international and multi-jurisdictional forums within Canada.”

The following story was published online Oct. 4.

By Shauna Lewis

The Missing and Murdered Women's Commission Inquiry is set to begin in Vancouver Oct. 11, but many women's and Indigenous rights groups won't be participating. Instead they plan to boycott the proceedings and protest against what they are calling a flawed, broken, and sham inquiry.

Members of the Downtown Eastside Women's Centre and the Women's Memorial March Committee are the latest non-profit groups to back out of the inquiry.

They were granted full standing during the proceedings, but say they are pulling out, in part, due to lack of provincial assistance for legal representation at the hearings.

The province has refused to provide legal council for many of the grassroots groups that had planned to participate.

Diane Wood, a member of the March Committee, said that decision effectively silences the most important voices of the inquiry.

"It is vital to this inquiry that the voices of women and the community be front and centre when determining its recommendations. Without a commitment to the participation of women from the Downtown Eastside, the inquiry is not legitimate and has no credibility,” Wood said.

“This inquiry has a responsibility to highlight those systemic injustices that allowed the unimaginable deaths and disappearances of so many women from the Downtown Eastside," said Carol Martin, victim services worker at the Downtown Eastside Women’s Centre.

"We have been raising awareness on this issue for over 20 years and demanding an inquiry for decades, but this sham inquiry is flawed and unjust. We cannot endorse it,” Martin said.

The centre announced Oct. 3 that it would no longer be participating in the inquiry following a discussion and vote by its members, residents of the Downtown Eastside.

Instead, the group said it plans to rally outside the Federal Court building on the opening day of the inquiry.

The Missing Women Commission of Inquiry was appointed by the provincial government last year to probe the conduct of police investigations of women reported missing from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside between Jan. 23, 1997 and Feb. 5, 2002. The mandate of the inquiry is to analyze police conduct and examine other aspects of the investigation regarding serial murderer Robert Willie Pickton, who was convicted of killing a number of women from the area.

Recommendations regarding safety and the future conduct of police investigations are expected.

But while community groups initially embraced the process, they now say the inquiry has been tainted by the commission’s lack of transparency. They allege the commission is biased and discriminates against those it claims it wants to protect.

"It's a joke," said Aboriginal women's rights advocate Bernie Williams.

"We're not going to get justice," she said. "They have it all sewn up."

The Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs, the Carrier Sekani Tribal Council, the Native Courtworker and Counselling Association of B.C, and WISH, a drop-in centre for sex workers in the Downtown Eastside, have also declined participation, saying that they can't afford to take part in the inquiry without financial help from the province.

Last month, the Pivot Legal Society pulled out because the B.C. government wouldn’t pay lawyers to represent sex-worker organizations.

David Eby, president of the BC Civil Liberties Association, said the issue is about more than a lack of government aid. He claims the hearing process has been muddled from the start.

"From day one there have been problems with this," Eby said. "[The government] has failed to set up a process that is agreeable and that works for the communities. [The inquiry process] has been with almost total disregard for the idea that the community of urban aboriginal people and women matter at all."

While police and senior government have full standing at the hearing, many community organizations were granted only partial standing by the commission, meaning they will have greater limitations placed on their participation.

"Since the beginning, this commission has been set up in a certain way that limits the [investigation] dates, that limits the ability for certain parties to ask questions, that limits the access of people to legal resources that will help them ask questions, and that pretends as if the sole purpose of this is to reconstruct what the police did 20 years ago," Eby said.

He claims that the commission and province are failing to see the bigger picture and that without a proper and fair inquiry nothing will improve.

“We are sick of this. This inquiry was supposed to be about a measure of justice for us and the hope that things would change down here, but it is just more of the same injustices,” said Beatrice Starr, who has resided in the Downtown Eastside for 30 years and whose sister and niece were both murdered.

Anger regarding the lack of community input in the inquiry process came to a head on Sept. 28 when 21 groups and the families of 17 missing and murdered women wrote an appeal letter to Premier Christy Clark, urging her to "intervene in this broken process."

The letter requested that the province assist the commission to make the inquiry more fair.

But in a swift and pointed response, Minister Shirley Bond, the interim Attorney General, told the groups the inquiry would continue as planned.

"Let me be clear. We will not be intervening in the work of the commission," she said in a statement last week.

"The government has called this inquiry to determine what happened and how we can prevent tragedies like this in future. We want to see this inquiry go ahead and we recognize how important its work is.”

Bond said budget challenges for the ministry have made the funding of legal counsel for the families of the murdered and missing women the priority.

“A public inquiry is designed to be an inquisitorial process, rather than adversarial," she explained. "Commission counsel can engage with all participants and witnesses and can lead all of their relevant evidence at any stage in the process," she said.

Bond said she was confident in the inquiry outcome.

"Lead commission counsel advised the ministry two weeks ago that the commission will be able to fulfil the mandate set for it despite the decision by participants with standing before the hearing commission to withdraw from the proceedings. The inquiry will be progressing in spite of these withdrawals and will hear from those parties that have chosen to participate," she said.

But the Civil Liberties Association claims that the province's response points to a shroud of secrecy engulfing the entire inquiry.

"When you have a vote of non-confidence, which I think that letter was, and nobody will step in, then really it's pretty clear what this inquiry was to begin with and that's not an inquiry about the community that asked for it. This is an inquiry for the police and for the government to put this issue to rest," said Eby.

"Unfortunately, all they're doing is opening old wounds as well as opening new ones."

But senior commission council Art Vertlieb, QC, said he thinks the inquiry process has been fair and says he "doesn't understand" community concerns and allegations of non-transparency.

"People applied for standing under the Inquiry Act and there were rules for that and when that was done months ago I don't think anybody complained about the way it was done," he said.

Asked if he thinks the mass boycott of the inquiry by community groups will affect its outcome, Vertlieb said no.

"I don't know why people would be so critical of our work when they haven't seen our work."

Vertlieb said it is business as usual for the commission council regardless of who participates in the hearing.

"[Community groups] have done what they think is in their organization's best interest and they have every right to make that decision and we accept it," he said. However, "I have a job to do and my job is to make sure that all of the relevant evidence is brought forward and the commissioner hears what he needs to hear."

Despite council's confidence, women's and Indigenous rights advocates remain sceptical and say they are bracing for disappointment.

"My foot feels pinned to the floor and I'm pivoting," said Williams. "Where do we go now?”

“[The commission and ministry] don't care about the impact this has on the people who are most vulnerable," said Kat Norris, and aboriginal rights activist and founder of the Indigenous Action Movement.

"They're making it so transparently unfair to the world and society," she added.

Mere due diligence is simply not good enough.

"It's sociopathic in nature," Norris said.

"If these hearings aren’t fixed so that sex-trade workers, poor women in the Downtown Eastside and Indigenous women can participate then there's no point of participating because all it will be is police lawyers talking to each other," Eby said.

"Frankly, it's interesting, but it's not going to make women any safer," he added.

Regardless of the inquiry outcome, the ongoing fight for justice and rights of the marginalized will continue.

"The people that are fighting for the missing and murdered women have hundreds, if not thousands, of women's voices and spirits inside them telling them to keep fighting," Norris said.

"I am going to keep fighting," she promised. "That's what I am here for."