Tseshaht First Nation has filed a suit under the federal Specific Claims Tribunal Act to recover (or to receive compensation for) the loss of the Iwachis Reserve at the mouth of the Franklin River.

According to the claim documents, Iwachis (IR 3), approximately 25 acres, was created in 1882, and was subsequently placed under the Indian Act. The site was an important fishing village, and several Tseshaht families, including the Gallics and Clutesis, had permanent residences.

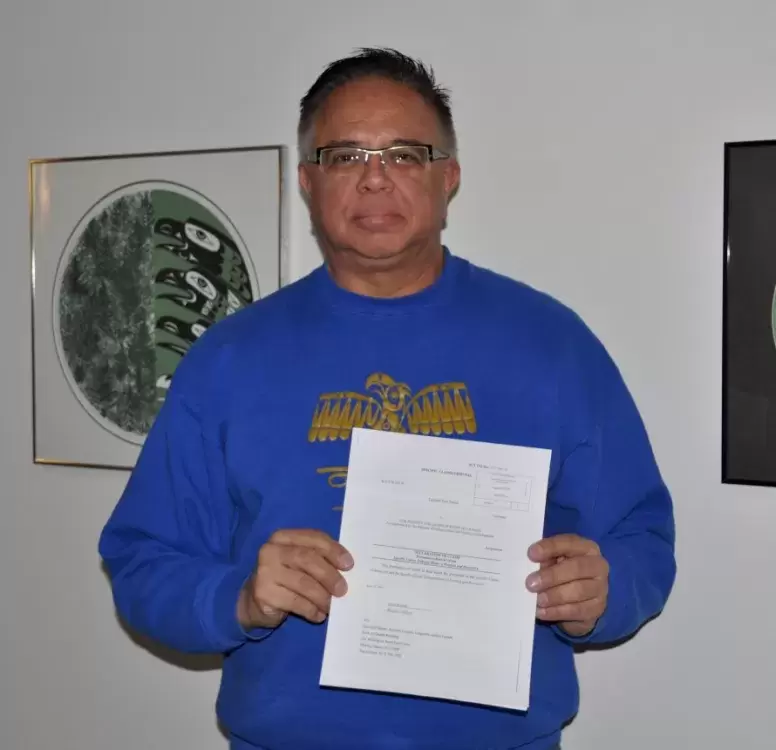

All that changed in 1913, according to Hugh Braker, who chairs the 13-member Comprehensive and Specific Claims Panel tasked with moving the lawsuit forward.

“At that time, the government came to tell the Tseshaht people that the land was needed for a railway,” Braker said. “They say they got us to surrender, but we say the surrender was illegal.”

The Franklin was a prime salmon river, producing chinook, coho and chum.

“Our people liked fishing there. There were also shellfish, as there always are at the mouths of rivers. Also, there was lots of wildlife. Even elk used to go down to the mouth of the Franklin River.”

The claim document spells out the convoluted series of events that led to the “surrender” of the reserve, beginning with the first approach by Green & Burdeck Real Estate Agents to West Coast Indian Agent A.W. Neill. Braker noted that there was some disagreement whether the Canadian National Pacific Railway needed only a small right-of-way or the entire site.

It is worth noting that Neill, who gained notoriety as the founder of the Alberni Indian Residential School, actually recommended that the railway pay a higher price per acre ($300 versus $200). After numerous disagreements back and forth, the Department of Indian Affairs decided to approve the sale, provided the “Reserve is duly surrendered by the Indians.”

Then, according to Article 26 of the claim:

“On February 18, 1923, 27 people allegedly signed the surrender. No records have been found describing the events of that day. Some of the people who signed the surrender did not habitually reside on or near the Reserve nor did they have an interest in the Reserve. Indeed, some of the people who signed the surrender were from other First Nations. Mr. Gallic and Mr. Clutesi resided on the Reserve. Neither of there men signed the surrender.”

On Feb. 25, “Agent Cox” forwarded a cheque for a total of $5,300 to DIA. But the papers weren’t made out correctly, and Cox filed again on March 26. This time, the papers did not meet Indian Act requirements. According to the claim, the final surrender document is “almost illegible.” But the Governor in Council approved the surrender on Sept 12, 1913: “executed as required by s.49 of the Indian Act, RS, c.43.”

“The railway was never built,” Braker said. “Even if they had, they wouldn’t have needed the whole reserve. They were supposed to insure that it was going to be used for what they said it was going to be used for, and they didn’t.”

The railway wasn’t built, nor the dockage facilities or terminal as spelled out in the application. By law, that should have triggered the return of the property to Tseshaht.

“The government broke their own rules,” said Braker. “[The proponents] were only supposed to use what they needed.”

But the property did contain marketable timber. In 1949, the parcel was sold to Bloedel Stewart and Welsh Ltd, and in 1980, to MacMillan Bloedel Ltd. The land has since been divested to Island Timberlands.

Braker said the goal now is to legally disprove the validity of the surrender process and the failure to properly compensate Tseshaht First Nation.

“It deprived us of a place to fish. We would still be fishing there today, if it was our reserve,” he said. “They kicked the people who were living there out. Who knows? There may have still been people living there today.”

Braker explained that, under the Specific Claims Commission, the government cannot be forced to give the land back, especially if the land was ceded to third parties – like MB/Island Timberlands.

“What Tseshaht is going to have to decide is – if the government wants to negotiate – do we want the government to buy the reserve back for us? Do we want the money? Do we want other land added onto one of our other reserves? We’re going to have to think about that.”

The matter is tentatively set for trial in November, and a pre-trial conference has been set for August. The case will be heard by Judge Grist of the Specific Claims Tribunal. A trial venue has yet to be set. Braker said it could be set for Ottawa or Vancouver, but Tseshaht will apply to have the case heard in Port Alberni.

“We will be having a meeting with our lawyer on March 19,” Braker said.

The Comprehensive and Specific Claims Panel is co-chaired by Ken Watts, and includes elders, one youth representative, the three seated Tseshaht Ha’wiith as well as a number of community members.

“That panel has exclusive jurisdiction over our comprehensive claim, and all of our specific claims,” said Braker. “We have a large number of [Specific claims]. We meet at least twice a month.”