It has been 45 years since the infamous Alberni Indian Residential School closed its doors for good, leaving behind a terrible legacy of pain for those that were forced to be there.

Over the years, Tseshaht First Nation, on whose territory the institution was located, has worked hard to erase the negative connotations that AIRS left in its wake.

“This is our homeland, our hahulthi, and we’ve had some successes over the years, like Haahuupayuk School,” said Darrell Ross, Research and Planning Associate for Tseshaht First Nation.

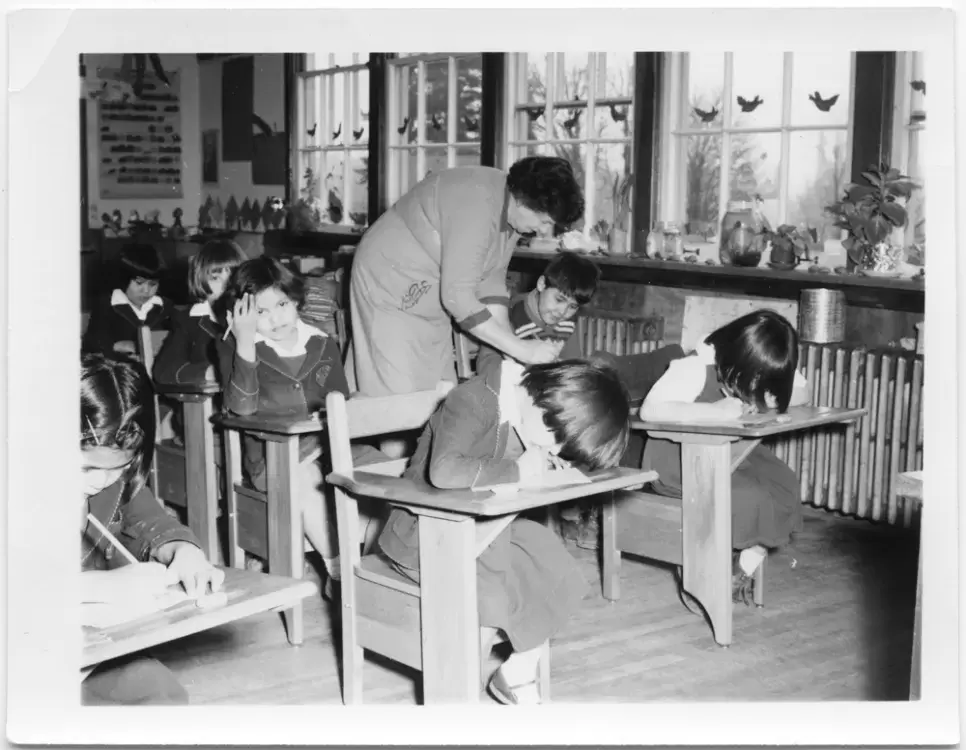

Haahuupayuk School not only delivers academic programs to elementary school children, but it is also revered for its cultural education programing. It is a major step toward rebuilding cultural knowledge while allowing children to live at home with their families, where they belong.

Tseshaht people have over the years worked on other projects in and around the site of the Alberni Indian Residential School, which was torn down not long before the construction of the present-day Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council building in 1989.

They removed the holly tree that stood at the entrance of the AIRS building, replacing it with a beautiful totem pole made by Tseshaht artist Gordon Dick. They tore the Peake Hall dormitory down, inviting survivors to take part in the demolition in February 2009. They installed a beautiful sculpture created by Tseshaht artist Connie Watts. It stands next to the traditional-style long house they constructed.

It is in the longhouse where, on Aug. 2, Tseshaht First Nation will be hosting an event that recognizes the historic day the Alberni Indian Residential School was shut down on Aug. 2, 1973.

“It has been 45 years since the doors closed for good and Tseshaht wants to celebrate this anniversary by looking at it as bringing children home,” said Ross.

He says his nation wishes to make this an annual event and they continue to work on ideas, like giving it an official Tseshaht name. But that is still to be decided on.

Why does Tseshaht want to recognize this day? Because, according to Ross, it was their own people that played a pivotal role in having the institution shut down, claiming it contributed to the breakdown of families.

“The West Coast District Council of Indian Chiefs (now Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council), in announcing it had negotiated the closure of the residence, cited the institution's role in breaking up the family unit as a major reason for the decision; the Council said it feels strongly that ‘with the power to effect change now within reach of Indian people, the thrust towards self- determination will be realized’," read a press release issued by the Tseshaht First Nation.

The event is open to everyone, including residential school survivors. They will be greeted and welcomed by Tseshaht leadership and will be treated to cultural performances.

There will be guest speakers and the microphone will be open for anyone wishing to speak. People are invited to bring flowers, photos, wreaths – anything they wish to commemorate loved ones.

Ross said his nation feels a need to do this, not only to celebrate that we have our children back, but also to remember what happened.

“We strove to rebuild and we still have some work to do,” said Ross. “We need to understand what happened to us over the past 150 years; we need to restore the harmony to our families and return to our culture.”