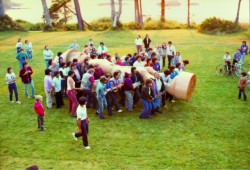

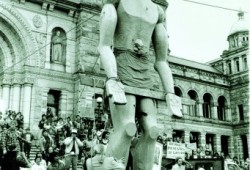

Thirty five years later, the image glows with iconic significance. With their shoulders bathed in the orange of a descending sun, dozens of men struggle to lift an enormous figure. The cedar man had just been erected for the first time by the beach at Tofino’s Tin Wis hotel, and in a symbol of brotherhood, the Nuu-chah-nulth-aht carry the 23-foot carving to begin a journey that will conclude before British Columbia’s legislature.

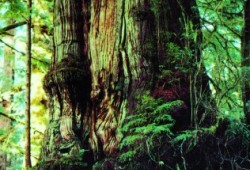

At that building in Victoria the cedar man would be erected again as a gesture of solidarity against plans to log Meares Island. Otherwise known as Wah-nah-jus Hilth-hoo-is, Meares was – and continues to be – home for the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation for countless generations, as well as part of Ahousaht territory along the island’s north. By the early 1980s the island that holds some of the largest cedar trees in the world faced the threat of being harvested under the provincial government’s tree farm licences – until the court halted this action with an injunction.

The cedar man had just been made over 21 days under the direction of Joe David, a Tla-o-qui-aht carver who, like many tied to the Nuu-chah-nulth community at the time, got caught up in the growing opposition to MacMillan Bloedel’s intention to log Meares Island. A short boat ride from Tofino, timber licences were first issued for Meares in 1905, and in these early days of forestry a small sawmill was built in the island’s Mosquito Harbour. By the time clearcutting began in 1955 most of the island’s forest was included within two tree farm licences.

But MacMillan Bloedel’s plans in the early 1980s represented an intensified form of logging, and court records show that within the first year of harvesting more of Meares’ trees would be cut by the forestry giant than in all of the island’s history. Many feared little would be left, including Moses Martin, who was the Tla-o-qui-aht’s elected chief at the time.

“We got news that there was planning that was going on for a number of years, that they were going to harvest 90 per cent of the island. We got really concerned,” said Martin, who again serves as the First Nation’s chief councillor in 2019. “We needed to take a stand and protect it.”

The stand they took was to declare Meares Island a tribal park on April 22, 1984, a designation that brought protection from industrial-style logging. Tla-o-qui-aht member Joe Martin recalls many evenings of elders talking about how to best protect their ancestral land and chiefly territory.

“We call it our hahoulthlee; the closest thing to it is a park,” he said. “We called it a tribal park so people understand there’s somebody in charge.”

The tribal park concept came from the Haida Nation, who were active in protecting South Moresby Island in their territory at the time. In his first year as president of the Council of Haida Nation, Miles Richardson was present when the Tla-o-qui-aht made their tribal declaration on that Easter Weekend in 1984.

“I was really inspired and encouraged at that moment 35 years ago,” he said.

Moses Martin recalls standing on Meares’ beach, thinking over how his nation’s resolve would best be communicated to MacMillan Bloedel’s logging crew.

“I was debating with myself, should I wait out in the water and hold them off, or should I welcome them to come join us for a meal, and I chose the latter,” he recalled. The elected chief would deliver the following words: “You are welcome to come ashore and join us for a meal; but you have to leave your chainsaws in your boats. This is not a tree farm – this is Wah-nah-jus Hilth-hoo-iss. This is our garden, this is a tribal park.”

The loggers would decline this offer, and multiple court actions from those on different sides of the issue would follow.

Responsibilities beyond minority interests

In the mid-1980s, Meares Island dominated the pages of Ha-Shilth-Sa. Among the many who expressed concern was 95-year-old Edith Simon, a member of the Clayoquot Band (Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation), who described using different parts of the island to collect medicine in a letter to the newspaper.

“Any unnatural disturbance would threaten the survival of our park,” she wrote. “I don’t want to see any logging on Meares Island at all.”

But in a published letter to the Friends of Clayoquot Sound, B.C.’s environment minister Anthony J. Brummet explained why the province was declining the environmental group’s request for a public inquiry into the plans to log Meares.

“The report on Meares took two years to prepare and there was ample opportunity for public input,” wrote Brummet. “The responsibilities of the Environment and Land Use Act must extend beyond the representations of minority interests and the decisions are made in such a way as to consider the overall benefits to the citizens throughout British Columbia.”

Dr. David Suzuki recently spoke about the movement to protect Meares Island with Moses Martin and Miles Richardson at an event in Victoria commemorating the 35th anniversary of the tribal park declaration. The scientist, broadcaster and author noted that MacMillan Bloedel’s logging plan came at a time when the province used to claim that 50 cents of every dollar in public services came from the forestry industry. The need to continue resource extraction is still rationalised by economic growth, as was heard during the Alberta provincial election in April, said Suzuki.

“The problem now is that the driving force is the economy, and you heard that in spades in Alberta - it’s jobs, and the economy,” he said. “Nobody talks about the bigger issues. The forest is a living, breathing being. As long as it’s alive and healthy it’s helping make the planet habitable for us. We don’t go in with a sense of gratitude and responsibility for caring for it because we get so much from it, that’s the whole problem.”

As evidenced by the stump of a tree that was cut on Meares Island in 1685 or earlier, forestry existed in the region long before modern industrial logging took hold. But as a carver, Joe Martin was taught a traditional protocol to carefully select a tree to use after several trips into the forest.

“Sit with it for a long time to make sure there’s no eagle’s nest, wolf dens or bear dens around,” he said. “Mother nature will provide for our need, but not our greed.”

Under the current NDP government, old growth logging is still very much a part of the province’s forestry plan. This year the provincial agency BC Timber Sales is set to auction off 1,312 hectares of old growth on Vancouver Island, compared to 1,022 hectares of second growth up for sale that was planted in the last 140 years, according to a study by the Sierra Club of BC. Within Nuu-chah-nulth territory, this is particularly evident in the Nahmint Valley, where the region south of Sproat Lake has seen some of Canada’s largest Douglas fir trees logged in the last year. And this April an area of old growth Crown land near Port Renfrew is being auctioned.

“It’s so sad to me the things that we allow to happen in our traditional territories,” remarked Moses Martin. “We all know about the global warming, we know about the forest fires, we know about the warming of the waters - but we still allow it to happen…I’d rather us find other ways of doing things, and alternative sources of whatever it is that we need.”

“Money grows faster than trees or fish; they drive you to be destructive, that’s the problem,” added Suzuki. “The game is rigged. Places like Meares are just a tiny, tiny hedge against the uncertainty of the future. The big challenge now if that we’ve got to reforest the planet.”

A marvel of an achievement

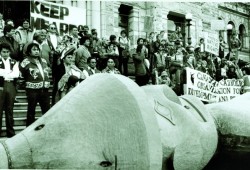

While Nuu-chah-nulth and environmental groups manned a blockade to the island, the different sides were facing off in court. The Tla-o-qui-aht and Ahousaht claimed Aboriginal title over the land, while MacMillan Bloedel argued that its right to harvest and build miles of roads had been unlawfully blocked when protestors prevented the company from surveying and preparing to log Meares.

The first decision ruled in favour of the forestry company when the Supreme Court of B.C. rejected the Nuu-chah-nulth request for an injunction to halt logging. But a few months later this changed when the B.C. Court of Appeal overturned this by granting an injunction on March 27, 1985. In a 3-2 decision, the panel of judges determined that logging should cease until the land claim issue is resolved – possibly through a treaty.

“It has…been suggested that a decision favourable to the Indians will cast a huge doubt on the tenure that is the basis for the huge investment that has been made and is being made,” wrote Justice Seaton in his judgement from 1985. “There is a problem about tenure that has not been attended to in the past. We are being asked to ignore the problem as [the province of British Columbia has] ignored it. I am not willing to do that."

Joe Martin’s father, the late Robert Martin Sr., had spent three uninterrupted months at the Meares blockade. After the court decision was made, an RCMP officer flew to the island by helicopter to deliver a document showing the injunction order.

“He shook my dad’s hand and said ‘You won’,” recalled Joe Martin. “My dad had a copy of that for years.”

The land claim issue was never resolved through a treaty, and the injunction remains in place, years after MacMillan Bloedel has ceased to exist as a corporate entity. This meant that Meares’ forest, which included some trees calculated to be older than 1,500 years, would still stand undisturbed. This victory began a decade of protests in Clayoquot Sound, a battle to preserve old growth that attracted international involvement and culminated in the arrest of 900 people in 1993 – considered the largest act of civil disobedience in Canadian history.

But decades later, Suzuki is at a loss to define how Meares Island changed forestry in Canada.

“It was a great achievement, but whether or not that influenced forest policy, somehow I doubt it,” he said. “But for me as an environmentalist, it stands as a marvel, and we in the non-Indigenous community can look to learn from it.”

“The fight to protect Meares Island is not just a fight for the Indigenous people of that area,” continued the scientist. “It’s a fight to protect a way that we can learn how things work.”

While old growth logging is still very much a part of forestry in British Columbia, Moses Martin is pleased to recall how the Tla-o-qui-aht, Ahousaht and other Nuu-chah-nulth people were able to unite in the face of a formidable industrial threat.

“Having our people come together for a common cause was really important for me,” he reflected.