One hundred and fifty nautical miles west of Vancouver Island, 814 metres beneath the ocean’s surface, lies the apex of an underwater volcano comparable in size to Mount Baker. Emerging approximately 2.5 kilometers up from the surrounding ocean floor, the Explorer Seamount is considered the largest underwater volcano in Canadian waters – yet despite its size, this giant and the life that inhabits it is surrounded in mystery.

“We know more about the moon than we know about the deep sea,” admitted Tammy Norgard, a scientist with Fisheries and Oceans Canada who has led expeditions over the past two summers to explore the deep sea volcanoes off Vancouver Island’s coast.

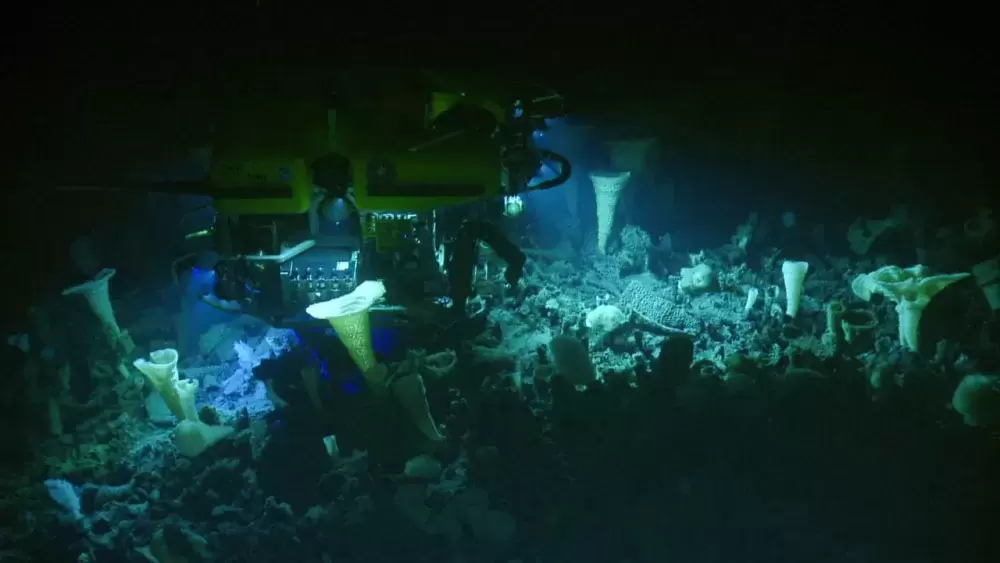

Now Norgard is at the helm of a two-week trip to focus on the Explorer Seamount, where she hopes to open some of the mysteries from the strange collection of images taken from the underwater mountain last year. The 2018 expedition found what appears to be a unique ecosystem on Explorer, including a monoculture of sea sponges.

“We’ve only had half a day of diving there, but our first indications were it looks very different from what we expected,” said Norgard of last year’s trip. “Because it’s so massive down there, it’s probably causing some different oceanography and currents, which would allow for different kinds of biological processes to occur.”

3-day journey to the apex

On July 16 a team of almost a dozen researchers left Victoria aboard the Canadian Coast Guard vessel JP Tully for the Explorer expedition. Besides several specialists from Fisheries and Oceans Canada, two people were invited to join the mission to serve the interests of Nuu-chah-nulth who call the waters west of Vancouver Island their home.

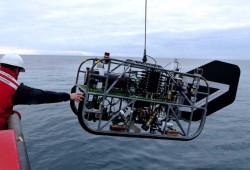

Aline Carrier is the capacity building coordinator with Uu-a-thluk, the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council’s fisheries program. When the coast guard vessel reaches its destination over Explorer’s apex on July 19, Carrier will be available to answer questions during a live online feed of video footage from BOOTS, the Bathyal Ocean Observation and Televideo System that will be lowered over the deep water volcano via a two-kilometre cable. Light does not reach past 200 metres below the ocean’s surface, so BOOTS is equipped with flood lights for its high-definition cameras.

Despite the distance from Vancouver Island’s shore, Carrier sees an important connection between the sea mount’s life and the environment that directly affects coastal communities.

“What will happen there in the next few years will influence a lot of what will happen on the coast,” she said. “These sea mounts could be really important for the biodiversity here.”

Tseshaht member Joshua Watts also joined the expedition after answering a notice posted by Uu-a-thluk for a Nuu-chah-nulth participant. A student in biology as well as earth, ocean and atmospheric science at the University of Victoria, Watts plans to be the “voice and ear” for Nuu-chah-nulth-aht during the DFO mission, where he will be sharing duties with Carrier to answer questions during the live video feed broadcast from BOOTS.

“Literally, our people come from this water. We’ve hunted, we’ve fished, we’ve whaled and we have that connection,” said Watts. “This is their territory that we’re going into. It’s just an opportunity to, in the present day, communicate and understand [seamounts]. I just think it’s super relevant to our people.”

Stories from ‘Old Buffalo’

Traditionally, Nuu-chah-nulth territory extends as far out into the ocean as the eye can see from shore. It’s not widely known if people ventured out as far as the Explorer or other seamounts, but elder Harry Lucas said indications can be found in a story told to him by Moses Smith of Ehattesaht, who was also known as “Old Buffalo”. As he recounted in Nuu-chah-nulth, Lucas spoke of offshore locations where people once saw bubbles emerging on the surface.

“There was always action somewhere in certain parts of the ocean. It would let out a steaming bubble,” translated Lucas into English. “They knew that there was something out there - that it used to boil now and then.”

This could allude to hydrothermal vents, emitting heated water, which characterize the underwater volcanoes.

“The Indians a long time ago were always afraid to dive to the deep when they seen something like that, because they didn’t know what it was. So it’s a known history,” added Lucas.

Watts considers the Nuu-chah-nulth tradition of whaling, and the long offshore excursions these hunts would require. Whales are known to congregate around sea mounts.

“I believe that our people were sometimes following the whales for so long that maybe they could have reached this far out,” Watts speculated. “I have read that our people would leave for days and sometimes weeks to hunt for these whales.”

An underwater mountain range

Explorer and other sea mountains west of Vancouver Island are caused by shifting continental plates, explained Norgard. These offshore volcanoes have not been active for a long time.

“It is multiple volcanoes that evolved, erupted, merged together to make a very large, I call it a mountain range,” said the expedition’s lead scientist.

Like other parts of the ocean, Explorer could be affected by climate change trends. The expedition aimss to look into how the volcano’s ecosystem is changing, while analysing the various depths of water that lead down to Explorer’s slopes. Carrier is tasked with this chemical and biological experimentation by lowering bottles over the mountain.

“More than 12 bottles go down to the bottom,” she explained. “On the way back up the bottles close at different depths, so you can have samples of water coming from different depths.”

Scientists have found a “naturally occurring oxygen minimum zone” in parts of the ocean, where the levels decrease in certain sections, said Norgard.

“You drop it past 500 or 600 metres and the oxygen drops…and then around 1,500 metres it comes back up again,” she described. “With climate change there’s potential that could expand. If that gets bigger, then animals used to having oxygen will have it taken away from them.”

Political interests

The federal government’s interest in these offshore mountain ranges have intensified in recent years, since the Trudeau government set the goal of a 10 per cent increase in Canada’s protected marine areas by 2020. In 2017 the government identified a massive offshore block west of Vancouver Island as an Area of Interest, thereby opening up the process of designating this region a Marine Protected Area. This would legally protect the 139,700-square-kilometre area from oil and gas exploration, fish bottom trawling and dumping, according to Canadian law.

More than twice the size of Vancouver Island, this Area of Interest includes the Explorer Seamount, plus another 45 known underwater mountains – comprising most of the 60 identified by the DFO in Canadian waters.

“We wanted to know what was there so we could know what kind of protections to put in place,” said Norgard.

Comprising 2.43 per cent of the ocean territory under Canada’s jurisdiction, the AOI west of Vancouver Island represents an important region on the federal political scene for multiple reasons. Besides being an area that could potentially help the federal government meet its marine protection target, the AOI would see a steady stream of increased tanker traffic if Ottawa’s investment in expanding the Trans Mountain pipeline is successful. According to a study by Kinder Morgan, Trans Mountain’s previous owner, expanding the pipeline’s capacity would increase tanker traffic from its export terminal from five vessels a month to 34.

Norgard expects that the current expedition will benefit conservation initiatives for Explorer and other seamounts.

“The more we can learn about them, the more we can understand them and the more we can protect them,” she said. “It’s informing the decisions about where we would allow different activities within an area.”

Watts expects that this month’s journey will bring discoveries from the distant underwater mountain, as well as more questions.

“The more that we study, the more that we understand that we really don’t know anything,” he said. “We build more knowledge, we build more facts, but we also build more questions. I think that’s just expanding our consciousness and expanding our belief system.”

Starting on Friday, July 19, see the live video here: https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/science/atsea-enmer/missions/2019/seamounts-s…