“The children were drinking water from toilet bowls,” said former school nurse Phyllis Ursel in letter written to Ellen Fairchild, then federal minister of Indian Affairs in 1960. At the time she had been working at the residential school in Alert Bay and was fired shortly afterward.

Phyllis Ursel was married with a family of her own. She worked in residential schools and was known for her kindness towards the little girls she was in charge of.

Ursel moved on to Alberni Indian Residential School, where she worked as a matron for more than 30 years.

While at Alert Bay, Ursel witnessed disturbing incidents. In her letter to the minister she wrote, “the older boys came to the dispensary at night for Aspirins because they had hunger-induced headaches. Because of a shortage of drinking fountains throughout the building, children were drinking water from toilet bowls.”

She went on to complain that there were only three bathtubs for 110 girls and that 57 staff members left the school in just over two years. Shortly afterward, she was fired, “for not being loyal to the school” according to Ursel.

Anglican official Henry Cook said Ursel was let go because she misrepresented her qualifications and had been disruptive.

Manila folder discovered

After a 30-year career as matron, or house mother, as granddaughter Rhonda Ursel called it, Phyllis passed away in a senior’s home in Port Alberni in 1998 at the age of 86. Phyllis’ husband Frederick had passed away years before; their belongings went to their son Frank

Frank Ursel, founder of the Clam Bucket restaurant in Port Alberni, stored his parents’ belongings in boxes in his basement until his passing in late 2019. A few months later, Frank’s daughter Rhonda took on the daunting task of sorting through two generations of items.

As she looked through boxes of her late grandmother’s effects, Rhonda came across a manila folder containing children’s poetry and drawings. They were the works of former Alberni Indian Residential School students dating back to 1958.

Rhonda said that she was told that her grandmother Phyllis felt compassion toward her young charges. She saved some of the works, which are now coming out of storage.

So far, only one manila folder of work has been found. Rhonda turned it over to her co-worker Rowena Cootes, who, in turn, contacted Ha-Shilth-Sa.

Rhonda was at first reluctant to make the find public, fearing that the negative connotations associated with Indian residential schools might bring pain and anxiety for people.

“I was afraid dragging up memories may be hurtful,” she told Ha-Shilth-Sa.

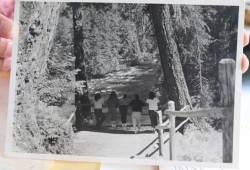

The folder contains a black and white photograph of a group of AIRS girls taken in 1959 at Cathedral Grove. Although beautiful, the photograph only shows the backs of the girls who are leaning over a railing looking into a creek. The back of the photo reads, “Some of our girls on a bridge. Cathedral Grove. Alberni Indian Residential School. Summer /59.”

The folder also contained signed drawings, along with a collection of poetry and other artwork. According to Cootes, Rhonda believed that her grandmother Phyllis felt sorry for the children who suffered from depression and loneliness. She would pay them a little money for their art and writings.

Writing under the holly tree

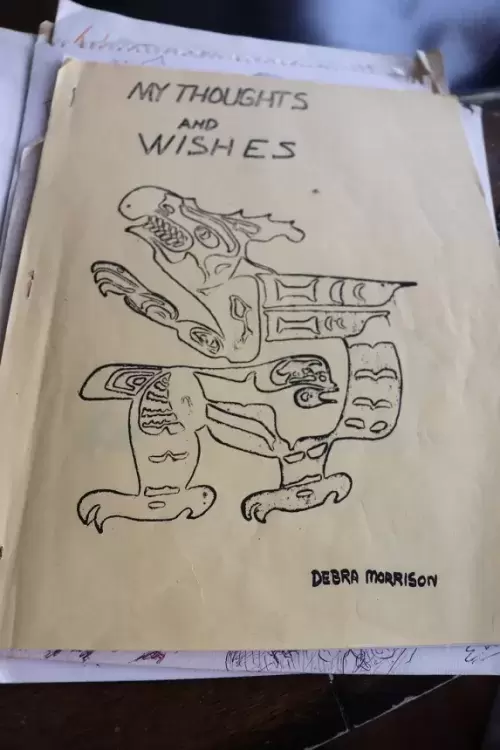

The booklet of poetry is signed by Deborah Morrison of Kitamaat Village. The poems, compiled in June, 1972, speak to the loneliness she felt and her views on racism. Others are reflections of what she was dealing with in the moment, like her final days in Port Alberni or her feelings about her family and her culture.

There are other poems in the booklet that were not written by Deborah, but they are unsigned.

Ha-Shilth-Sa located Deborah, now married and going by the last name Hayward. She shared her memories of Phyllis Ursel.

“I remember her fondly,” said Deborah. “I could go to her room anytime and tell her when I was afraid and she would sit down and listen.”

“We felt so comfortable around her, she was nice, she was fair to us,” she shared

Of her poetry, Deborah said she started writing because of the loneliness caused by being away from family. AIRS survivors were given chores to do, but even then, there was still a lot of time on their hands.

“I would go for walks and find time alone. I’d take a book, find a trail nearby and write, or I’d go under the holly tree to write,” she said.

Deborah didn’t quite understand why she was sent away to AIRS and, as children will do, blamed her weak grades as the cause. She was determined to do better so she could go back home.

“I tried really hard in school because I thought that’s why I was sent away; I worked on projects, committees, played basketball and other sports, I would be called out of class to teach other kids how to make fried bread,” she recalled.

A positive voice during a dark time

Deborah believes she was at AIRS from 1969-72. The booklet of poetry was a class project and about 100 copies were made. Deborah gave a few copies away to very special people, including Phyllis Ursel. She didn’t save one for herself.

Deborah said that Ursel was known to give and receive little gifts from some of the girls. She gave Deborah a cross necklace.

“I treasured it and took good care of it,” she said.

But with all her hard work, Deborah never did return to the family that she was so lonesome for.

“By then, the family had broken up, everyone was blaming each other for the kids being taken away to residential school,” said Hayward.

She went into foster care in Duncan and then another one in Kitamaat. She graduated with excellent grades in 1974 at her home village. Now age 64, Hayward is living back home in Kitamaat Village.

“I’ve done a lot of healing, counselling and working on our native language,” she shared.

She remembered other AIRS workers who were kind to the children. There was Hortense the cook who found out kids were breaking into the kitchen at night because they were so hungry. According to Hayward, Hortense got permission to come to AIRS on the weekends to teach the kids how to make small snacks for themselves.

And then there was Penny. She would take the girls on field trips and picnics.

“I don’t remember her last name but she was young and had a boyfriend, so she’s probably married,” said Hayward.

Penny was so well-liked that Hayward named her daughter after her.

Rhonda Ursel is delighted to know that her grandmother left a positive impression of the children of AIRS. She has given the collection of work to Ha-Shilth-Sa in the hopes that they can be returned to the original artists or kept in archives.