Following an alleged racist attack over a parking altercation in Campbell River, a Kyuquot woman was sent to hospital with non-threatening injuries last Thursday, Dec. 10.

All parties have been identified and the incident is still under investigation.

“At this point the details we can share are extremely limited,” said Campbell River RCMP Const. Maury Tyre. “In situations like this, we try and maintain contact with [all parties] and see if we can find a resolve.”

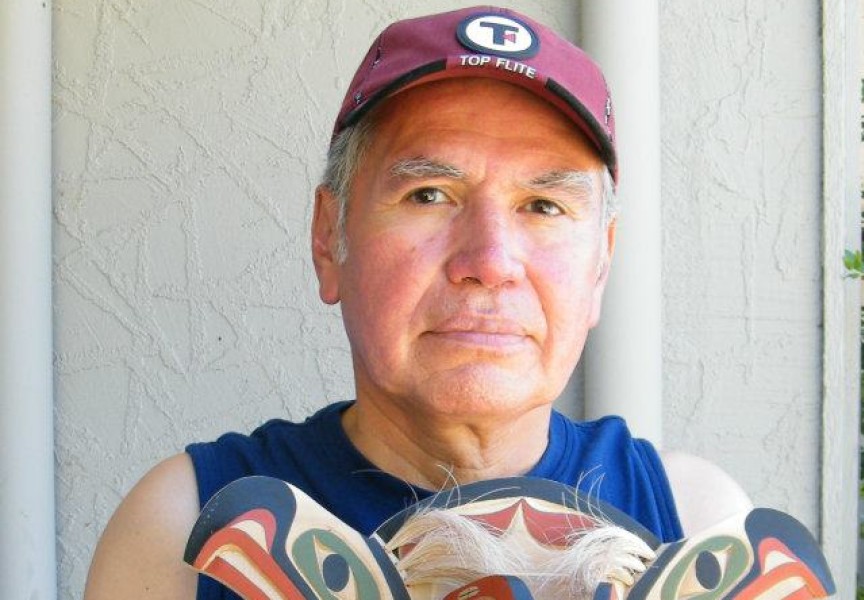

A member of the Ka:'yu:'k't'h'/Che:k'tles7et'h' First Nations and her daughter had travelled to Port Hardy from their home in Kyuquot to attend a medical appointment. They continued on to Campbell River for groceries before returning to their remote community.

At around 6:30 p.m., she parked outside of Boston Pizza to pick up dinner. When she returned to her vehicle, a woman was yelling racial slurs at her teenage daughter, and a man had pulled up behind their truck, blocking them in, said the woman.

“Everything started over parking,” said Tyre. “And it kind of went from there.”

“We spent three days in our hotel room freaked out (afterwards] – we didn’t know what was going on. I had to help my daughter out of bed – it was so heartbreaking to see her going through that,” she said. “I had a long stressful day waiting on results for cancer for God's sake. We didn’t do anything to this couple. We did not initiate contact with them. They wouldn’t let us leave.”

Different options are being looked at in trying to deal with the situation, explained Tyre.

One of those options is restorative justice, which can be an alternative to incarceration. This approach holds the offender responsible for a crime, but seeks a resolution between those affected by addressing the harm caused to the victim.

Restorative justice is gaining more attention as the province seeks to integrate the First Nations justice strategy into how it deals with crimes, but as she deals with her injuries and the harm caused to her daughter, the woman said it is not an outcome she is comfortable with.

“I absolutely do not agree with restorative justice [as an option],” she said. “It’s not for something that’s violent like this.”

Before joining the RCMP, Tyre worked as a restorative justice facilitator and said that the variety of cases the model deals with is “huge.”

“For the most part, when people think about [restorative justice] they immediately think that it is only used for property crimes,” he said. “But it can be used for so much more.”

From sexual assault to aggravated assault, Kristine Atkinson, program coordinator for the Campbell River RCMP restorative justice program, said that it can be a good alternative to the punitive court process.

“You can address the matter in a more timely fashion – while the party is still feeling the harm,” she said. “It’s focusing on the harm caused in the situation and resolving that harm.”

Not only does the restorative justice model lower recidivism rates, but the satisfaction level is higher for the victims, said Atkinson.

Based on a circle process, a facilitator tries to elicit conversation between both parties involved in a crime. By coming to a mutual understanding of what happened, what harm was felt and how the participants best see that harm repaired, the end result is a resolution agreement of how the offender is going to make amends.

Fundamentally, restorative justice tackles crime through healing.

However, its other vital benefit is addressing what correctional investigator Ivan Zinger describes as “one of Canada’s most persistent and pressing human rights issues” – the overrepresentation of Indigenous people being incarcerated.

As the proportion of Indigenous peoples behind bars surpassed 30 per cent this year, “the pace is now set for Indigenous people to comprise 33 per cent of the total federal inmate population in the next three years,” Zinger said in a release.

“It is not acceptable that Indigenous people in this country experience incarceration rates that are six to seven times higher than the national average,” he said.

In effort to address these historic heights, The BC First Nations Justice Strategy was developed over the span of two years by First Nations communities, the BC First Nations Justice Council and the province.

One of its aims was create a pathway for the re-emergence of First Nations self-determination and jurisdiction in the justice sector.

Indigenous women make up nearly half of new admissions to adult corrections in B.C., despite accounting for less than six per cent of the general population, according to the strategy.

“Indigenous women and girls are over policed and under protected,” said Don Tom, vice-president of the BC Union of Indian Chiefs, in the strategy. “Indigenous women who are survivors of crime often don’t trust the police enough to report it and face criminalization when they do. When involved in the criminal justice system, Indigenous women and girls are more likely to plead guilty, receive longer sentences and less likely to have adequate legal representation. This strategy brings justice system attention and resources to creating better justice system outcomes for women and girls.”

As the Kyuquot resident’s case is still under investigation, restorative justice is not off the table. However, it can only function if both parties are willing participants.

“It’s dependent on if it’s acceptable by the parties and if it’s suitable for the matter,” said Atkinson. “Each matter has to be looked at individually.”

For the time being, the incident will remain a disturbing confrontation for the Kyuquot resident that didn’t need to escalate as it did.

“It didn’t need to go that far,” she said. “We’re both quite sore – I keep going over 'what did I miss? What did I miss?'”