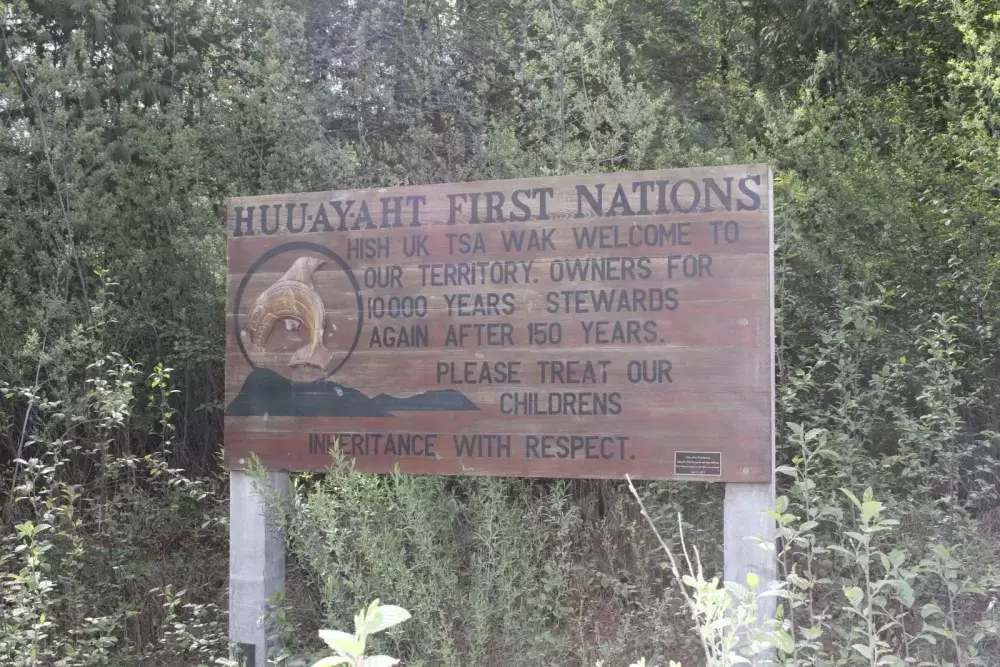

In a move to prevent dangerous clashes from forestry protest activity in it’s territory, the Huu-ay-aht First Nations have introduced a checkpoint halfway down the road to Bamfield.

The checkpoint went up today on Bamfield Main. If a driver isn’t recognizable, personnel will inform the visitor that while in it’s ḥahuułi, Huu-ay-aht’s three sacred must be followed: ʔiisaak (Utmost Respect), ʔuuʔałuk (Taking Care of), and Hišuk ma c̕awak (Everything is Connected).

“People who violate our sacred principles are no longer welcome on our ḥahuułi,” reads a notice given to visitors at the checkpoint. “Violations will be dealt with to the full extent of the traditional laws of the Huu-ay-aht Ḥaw̓iih and the laws of the Huu-ay-aht Government and Canada.”

The checkpoint was announced on Friday, May 7, one day after the First Nation reported that a logging protestor had driven through a safety barrier onto an active cutblock to remove signs.

“They’re endangering their lives and endangering the workers there - for us that’s unacceptable because we have to be concerned about the safety of our workers,” said Chief Councillor Robert Dennis Sr., noting the Huu-ay-aht’s growing stake in Tree Farm Licence 44, which extends across much of the First Nation’s territory. “With us being on the other side of the ledger now that where we’re 35 per cent owners we have to be concerned about our workers.”

After the May 6 incident TFL 44 LP, a partnership co-owned by the Huu-ay-aht and Western Forest Products, engaged conflict resolution specialist Dan Johnston. He is assigned to prepare a report and recommendations on how to ensure safe forestry practices while allowing people to exercise their right to peaceful, legal protest.

Dennis said that the First Nation is not against protesting, but it must be done in a respectful way that doesn’t endanger forestry workers.

“Some of those people are our people,” he said. “We now have 16 Huu-ay-aht people working in forestry operations.”

Tensions have been rising recently across southern Vancouver Island, as a growing number of blockades and protest camps are being established by the Rainforest Flying Squad, a loosely affiliated collective of activists taking a stand against old-growth logging. Their first blockades were set up in August last year to prevent road building into the Fairy Creek watershed, an area near Port Renfrew that is believed to be one of Vancouver Island’s few valleys still untouched by industrial logging.

The Huu-ay-aht have heard of loggers finding spikes in trees in the Fairy Creek area, an old technique used to disrupt harvesting that became common during the large-scale protests in Clayoquot Sound in the 1990s. Tayii Ḥaw̓ił ƛiišin, Derek Peters, doesn’t want the same hazardous measures undertaken in his territory.

“We don’t agree with that approach,” said ƛiišin. “We’d much rather have people come and ask permission, and say what they’re here for, and get information from us.”

While standing at the checkpoint, which lies at the entrance to his nation’s territory, ƛiišin pointed to the historical impacts of logging evident in the surrounding area. Not far from the checkpoint the enormous Camp B was located, which at its peak house as many as 400 forestry workers. As the Huu-ay-aht claim a growing stake in the industry, ƛiišin noted that his nation has had to work with some of its own members opposed to logging.

“We have people in Huu-ay-aht too that are against what we do as well,” he said. “When you look around here and you see how much devastation has occurred through forestry practices since forestry started, it takes time for change to happen.”

Dennis added that logging intensified in Huu-ay-aht territory after much of Clayoquot Sound became protected a generation ago.

“The other thing that people don’t realise is that when Clayoquot Sound was successful in their protests and they quit cutting over there, well guess what? They had to cut somewhere else,” he said. “B.C. declared Huu-ay-aht territory a forest enhancement zone.”

But since then the annual timber harvest has declined from approximately 1 million to 500,000 cubic metres, and now the Huu-ay-aht are placing a greater emphasis on planting western red cedar, after Douglas fir was the mainstay for replanting before the 1970s. For each cubic metre harvested $5 is reinvested into salmon habitat renewal work, adding to the $375,000 Western Forest Products has already committed in watershed enhancement projects.

“We’re in a good position to start influencing management in a way that incorporates our values as Huu-ay-aht people,” said ƛiišin. “What you take out you must put back in is the philosophy we go by in our value system.”

In any given year forestry accounts for 60-80 per cent of the Huu-ay-aht’s revenue as a First Nation with a modern-day treaty. Meanwhile tourism accounts to about 1 per cent of what the First Nation takes in, said Dennis, who noted that providing employment opportunities needs to be considered while managing the Huu-ay-aht’s natural resources.

“We’ve got to balance the two: we need an economy, but we also need a healthy environment,” he said. “If you can find an alternative way that we can have an economy, bring it to us. Nobody is coming forward.”

Meanwhile, 7,000 hectares of old growth in Huu-ay-aht territory remain protected, as this is part of the Pacific Rim National Park Reserve. The nation is planning 150 years ahead, and now ƛiišin has the authority to decide which second growth will become old growth over a century from now.

“He now has the ability to say, ‘I want to set that aside for future generations’,” said Dennis.