As the arrest toll grows at blockades around the Fairy Creek watershed, some wonder if police enforcement in the area is going beyond stipulations of a court order, while interfering with civil liberties.

RCMP have so far arrested 127 people in the area near Port Renfrew, including nine who have been taken away more than once. In mid May police moved into the area to enforce a court injunction against protestors who have been blocking forestry access into the Fairy Creek watershed since August, which is considered one of Vancouver Island’s few remaining old growth valleys untouched by industrial logging.

On April 1 the B.C. Supreme Court gave an injunction to Teal-Cedar Products, prohibiting the interference of its harvesting or access to the watershed, an order which lasts until Sept. 26.

The injunction covers a large area, extending from north of Port Renfrew to the Nitinaht River, covering both Pacheedaht and Ditidaht territory. When the order was issued eight blockades were identified, resistance held by the Rainforest Flying Squad, a loosely affiliated group of old-growth activists, for over nine months.

“The purpose is to prevent a further escalation of efforts to block access contrary to the Supreme Court order, and to allow the RCMP to be accountable for the safety of all persons accessing this area given the remoteness and conditions,” reads an RCMP press release.

The court order makes multiple mentions prohibiting the “obstructing, impeding or otherwise interfering” with Teal-Cedar Products’ forestry operations in the area. While the injunction does not bar access to the area, it does give RCMP authority to arrest anyone “who the police have reasonable and probable grounds to believe is contravening or has contravened any provision of this order.”

As a result, entry into the injunction area has been tightly controlled, with checkpoints and a temporary access control area along the McClure Forest Service Road, which is located north of the Fairy Creek watershed. Since then protestors have been given the option to “abide by the terms of the injunction and leave the area, or relocate to the designated protest/observation area set up by the enforcement team, or face arrest,” according to an RCMP release.

Sgt. Chris Manseau of RCMP media relations said the police’s major concern is maintaining public safety.

“A lot of these protestors have put themselves in situations that are extremely dangerous, climbing very high trees, chaining themselves to large objects that are unstable and staying out in the bush without proper food or medication for quite some time,” he said. “We understand that people in the area have the right to protest if they’re going to do it lawfully and safely. We just want to make sure that nobody gets injured in any of this.”

While a growing audience is looking to Fairy Creek as an indication of how old growth is being managed in the province, journalists appear to be depending on police to be taken to places where they can observe and report on developments. The Ha-Shilth-Sa relied on police escort to be taken into the enforcement area, once waiting for hours to get a closer look at the unfolding scene.

Manseau said the escorts are needed to ensure public safety while industrial logging operations are underway.

“I’ve been inviting journalists where enforcement is planned to take place,” he said. “There has been the odd time when somebody wasn’t allowed, however we have tried to remedy that as best we can with the resources that we have. There is no intention to not allow journalists access.”

Such limits on freedom of the press go against the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, says Brent Jolly, president of the Canadian Association of Journalists.

“Journalists have the right to report information freely. When you have an injunction like this that prevents people from doing that, I would argue that’s limitation of freedom of the press.”

Jolly believes enforcement would be different in less remote setting with more people observing.

“It seems like if this were going on in Stanley Park, or somewhere, the police reaction would be far different than what we’re seeing here,” said Jolly. “In this case, I really don’t see how restricting access in the way that they have is fair or reasonable. This is not a combat zone where journalists need to be sure that they’re off to the side.”

Manseau admits that is has been a challenge to verify who is a journalist working for a reputable media outlet. He said the RCMP is exploring an accreditation process similar to what the BC Supreme Court uses to allow reporters into the courtroom.

“Unfortunately, we have come across a couple of times so far where people have claimed to be journalists and then have been escorted in, granted access, and then have joined the protest,” said Manseau.

In a letter to Minister of Public Safety Mike Farnworth and top RCMP officials, the BC Civil Liberties Association argues that restricting access to the enforcement area, which is on Crown land, is unconstitutional according to Canadian law.

“This situation is alarmingly reminiscent of what occurred in Wet’suwet’en territories last year,” wrote the association.

The BCCLA also referenced the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which states that “Indigenous peoples have the right to the lands, territories and resources, which they have traditionally owned, occupied or otherwise used or required.”

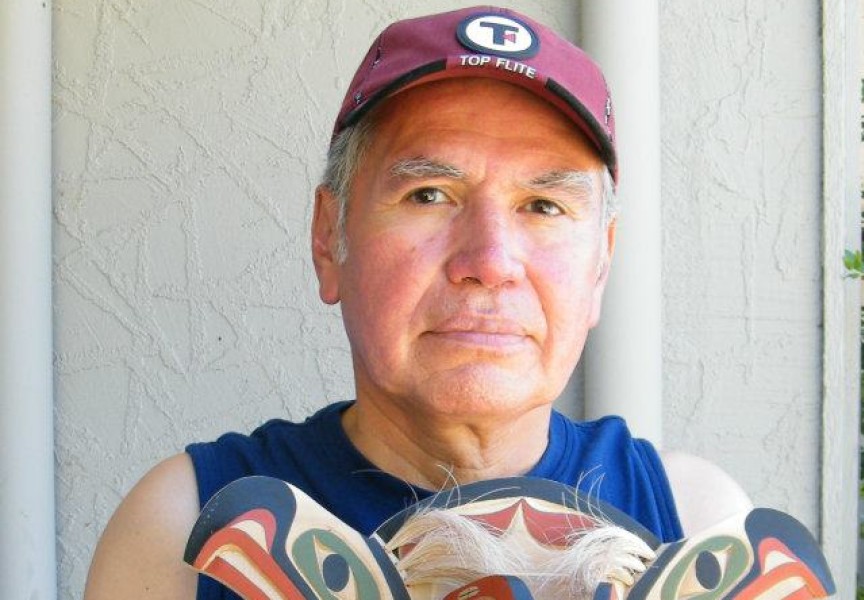

Pacheedaht elder Bill Jones didn’t feel that these rights were being upheld when he was denied access into the Fairy Creek valley in mid May. Although the Pacheedaht First Nation has formally opposed the presence of protestors in the area, Jones is among his community’s most vocal supporters of the old-growth movement.

“The road that they’re on that the police are blocking is actually a public thoroughfare,” said Jones. “I couldn’t proceed past them. They blocked me off and sent us all away. So that means that I’m affronted and denied of my rights and freedoms of access to my own territory.”

-With files from Melissa Renwick