During art class at the Wickaninnish Community School in Tofino, Dominic Hansen eagerly volunteered to introduce himself to his class.

Despite having already been in school together for nearly three months, Hansen’s classmates listened to him attentively, as if they were hearing him for the first time. In Nuu-chah-nulth, he shared his name, his parent’s names and where he comes from.

Nuu-chah-nulth peoples commonly introduce themselves by sharing more than just their name, said Dani Stone, the school’s vice-principal and fine arts teacher. They describe where they have roots, the names of their parents and grandparents, as well as the territory they currently occupy.

The formality is one Stone encourages the children to regularly practice.

“It’s a way to make connections,” she said. “Identity is so important. Ultimately, we're trying to help kids to be able to advocate for themselves – to know who they are.”

Nuu-chah-nulth language and cultural teachings are woven into the school’s everyday curriculum.

You’ll often hear Stone reminding her students to show “iisaak,” meaning respect, to each other. And instead of saying, “thank you,” at the end of the class, Stone will say its Nuu-chah-nulth translation, “kleco-kleco.”

“It’s so important for kids to see themselves [and to] understand that we’re on Tla-o-qui-aht territory,” she said.

Even the student’s art projects are entirely inspired by Nuu-chah-nulth culture.

Under the guidance of Grace George, First Nations support worker for School District 70, Darlene Frank, the school’s Nuu-chah-nulth education worker, and Corinne Ortiz-Castro, Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation homeschool coordinator, the art classes integrate First Nations symbols and traditional sewing practices.

Before COVID-19, Stone said the fine arts program consisted of more performance-based classes, such as music and drama. But when lockdowns and social distancing measures made it difficult for some children to regularly attend class, Stone said they needed to switch gears.

“We were trying to build school community without being allowed to be together last year,” said Stone.

By transitioning the focus to visual arts, Stone said it gave students a “place to enter wherever we were with our learning.”

For students like Payton Black, the shift felt natural. The 10-year-old has been sewing for years after being taught by her grandmother.

“When I’m nervous, I sew,” she said. “It’s fun.”

The emphasis on visual arts has allowed students, like Black, to step into the spotlight and share their skills with friends, said Stone.

Through a progression of increasingly more intricate art projects, Stone is trying to develop the student’s confidence. They are building up to create a design that will be sewn onto the school’s regalia and left behind as a legacy piece.

Many years ago, George told Stone that she dreamed of seeing the entire school dressed in regalia designed in the school’s colours while performing Nuu-chah-nulth dances for the entire community.

This year, Stone said, the school is working towards that goal.

Community members and school staff have been sewing vests and shawls so that there is one for every student.

While the gathering hinges on the situation surrounding COVID-19, Stone said she remains hopeful.

“One day when we return back to a more normal time and we're able to gather safely together, we hope to have our community come together to celebrate with us,” she said.

Over the 28 years that George has been working as a First Nations support worker, she said she’s seen a big shift in the way the community and Nuu-chah-nulth peoples have embraced their culture.

As recently as 10 years ago, George said that students wouldn’t identify themselves as being from Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation.

“They just weren’t told,” she said.

Now, even the most quiet and shy First Nations children say who they are “loud and proud,” George said.

The 67-year-old never went to residential school, but her older brother, Billy, did.

“He was really, really badly beaten,” she said. “But he never forgot the language.”

Billy became her mentor when she began studying Indigenous language revitalization and proficiency at the University of Victoria, where she recently graduated with a diploma.

“When I started taking the language course, he couldn't believe that he went from being beaten to being paid to teach me the language,” she said. “It's really evolved and it's so nice to see. Tofino and this school have been really accepting of our language.”

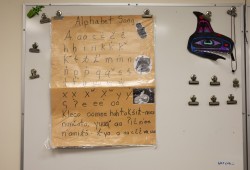

The Nuu-chah-nulth alphabet, which contains 46 letters, hangs on the white board at the front of the classroom.

It’s not easy to learn, but George said some students picked up on the language “right away.”

Eddie Dyrchs moved to Tofino from Germany with his family three years ago. Because Nuu-chah-nulth and German share some of the same guttural sounds, George said the language has come to him easily.

The nine-year-old said that Nuu-chah-nulth reminds him of German and has been “really fun” to learn.

“Land-based learning is so important,” said Stone. “That’s the stuff that really resonates with the kids.”

Stone said she laments that she didn’t receive Nuu-chah-nulth teachings when she was in school.

“I feel like I’m catching up as an adult,” she said.

The vice-principal said she’s “blessed” to have received so many different teachings from Nuu-chah-nulth members and education workers. It’s a gift she wants to share with her students.

“I see the joy and pride on parents’ faces and kids’ faces when they learn those [cultural] pieces,” she said. “It helps to build connections within the students.”