As a student at the Christie Indian Residential School, Ray Williams recalls the excitement of getting his monthly chocolate bar. He also remembers the joy of a film night in the institution. From the darkness of the girls’ gym, the flickering image acted as an introduction to the modern world for a child who had never seen a movie before.

Such pleasures brought a critical light to the five-year-old’s world, after he had been taken from his Mowachaht village of Yuquot with other children. In 1946 hundreds still lived at the ancient settlement on Nootka Island, but when a steamship arrived one day to pick up the young ones an irreversible process was underway for the young boy and his people.

“While we were on that steamship, we didn’t know where we were going to,” recalls Williams. “The children were playing around on the deck, having fun, laughing, playing tag.”

No. 37

At the end of the journey lay Christie, a Catholic-run residential school on the shore of Meares Island, near Tofino. Williams’ boyhood Mowachaht name was discarded, as was his native tongue, and he became known as No. 37, learning to answer the brothers’ role-call each morning in Christie’s basement.

To this day Williams dislikes the number.

“It brings back terrible memories,” says Williams. “I knew it right away, because they told us it’s important to remember that number, we’ll be calling you by the number, not your name.”

Within Christie’s walls the world took on a peculiar meaning. Williams recalls being led to believe the behaviour of the adults who ran the institution was normal – even if abuse went so far as sexual assault in the boys’ bathroom at the hands of two priests.

“We all thought that was a normal thing for them to do to us,” he says. “I had actually seen one of the brothers doing that to a boy about my age in the bathroom. The bathroom was open…it had no door.”

A bizarre series of other measures were imposed on the children, including some that still leave Williams wondering.

“I got 30 shots on each arm, and 60 on the base of my spine. The needle holes are still there,” he recalls. “To this day, no one ever, ever told me what they were for.”

‘I feel the pain there again’

As it was the school’s responsibility to manage the grounds around Christie, children were often engaged in labour, like building roads. One accident at the age of 6 or 7 left a lifelong mark on Williams, when he was helping to move a trailer full of boulders up a hill. The rickety thing was being pulled by a tractor with the school’s maintenance worker at the wheel.

“We just couldn’t get up the hill far enough to go over to the flat ground. He ordered some of us to help turn the wheel on the trailer,” Williams remembers. “Some of us were pushing from the back of the trailer, some of us were helping to turn the wheel to go up.”

In the struggle the young boy stumbled, causing the back wheel of the trailer to run over his body.

“I don’t remember when it rolled over, I was already in shock,” says Williams. “It broke open two big cuts behind my knee, halfway up my ankle to my knee at the back of the leg, and it broke my right foot.”

Two older boys, Earl Smith and Ralph Amos, carried the injured Williams to the school’s dormitory, where he would remain to heal. Medical treatment consisted of wrapping the broken limb in cloth.

Despite never going to a hospital or seeing a doctor, the young boy healed, although he had to wear a shoe one size larger than the other to accommodate for the lump that resulted from his injury. As an adult while working as a logger he even stuffed one of his cork boots with cotton to accommodate.

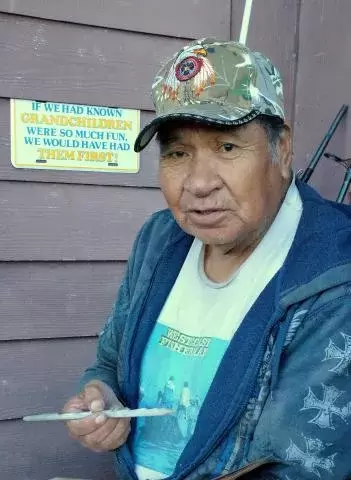

Now at the age of 80, Williams reflects on an active life. Yet as he looks over the bay from his Yuquot home, the elder has recently noticed the distinct pain from his early childhood return.

“That lump that was on that broken foot, it slowly went down over time because of my age,” says Williams. “Now today I feel the pain there again.”

A change in trajectory

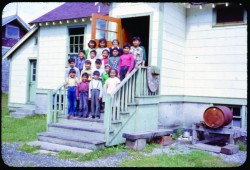

The trajectory of his life was altered in 1950, when Williams and other children were sent back to their Yuquot home to attend an Indian day school that was to be run in the remote community.

“Our school desks were the benches that were lined up in the church,” he says of this happy period. “We always looked forward to going to the lake over here. When I came home I was so happy, I wanted to run and jump into the lake, because that was our favourite playing grounds.”

But as the nine-year-old reintegrated into his home, the mark of the residential school period remained evident. Williams was adept at handwriting, which he continues to use to this day, and spoke English to the other children. He recalls one boy laughing when Williams responded to Mowachaht in English.

“I got kind of upset why he was laughing at me, talking English,” he says.

But fluency in his ancestral language returned, as connection to his birthplace fortified. At the age of 21 Ray married Terri, who had lived on Nootka Island for her whole life, thanks to her family hiding her in the woods as a child when the Indian agent arrived for a residential school collection.

The memories from his early years at Christie festered for years, turning into disdain for the race of his oppressors that lasted well into adulthood.

“For many, many, many years I just hated white people,” admits Williams.

But over time this changed, thanks in a large part to an unexpected friendship with Bill Conconi, a Victoria-area teacher who started visiting Yuquot in 1975.

“He came to me, about 40 years ago in a sailboat, and started talking to me about how I treated other white people,” says Williams. “He didn’t preach to me, he just talked to me. We talked about fishing, talked about hunting, about the things I wanted to talk about. A few years later it changed my thoughts about the white people. ‘Oh, they’re not all that bad,’ I said to myself after I met this man here.”

The friendship matured, and two of Williams’ sons even lived with Conconi’s family for two years to attend Mount Douglas Secondary, where Conconi taught. Williams’ daughter stayed with the Conconi’s for five years for her secondary schooling.

“When the kids were staying here lots of times they were hiding in the driveway and they would surprise me,” recalls Conconi of coming home to the Williams teenagers. “I would go up there for the summer. Ray and I would go fishing, I’d make the coffee and he would drive the boat. We had a lot of fun with that.”

Ghoo-Noom-Tuk-Tomlth

Although the Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation’s reserve community was moved to Gold River in 1967, the lure of new houses did not dissuade Ray and Terri, who kept their home in Yuquot for the nearly 60 years they were together. By the time Terri passed in September 2020, the family had been the only remaining household in the ancient village for many years.

“We always told each other, ‘We belong here, we don’t belong elsewhere’,” says Ray.

As a man, Ray took the name Ghoo-Noom-Tuk-Tomlth. A far cry from No. 37, it means “Spirit of the Wolf” in Mowachaht. He even has it on his fishing licence.

“It makes me proud of myself.”