This month the Royal B.C. Museum began construction of a 164,000-square-foot building to house its collections that aren’t on display, but the institution doesn’t plan to include its First Nations pieces in this new facility.

Instead, as the RBCM aims to be “more proactive rather than reactive” in returning certain Indigenous artifacts to their home communities, it intends to keep the First Nations pieces at the main downtown location to facilitate more repatriation opportunities in the future, according to the museum’s communications department.

“Through conversation with community, the intention has been to continue to keep Indigenous collections at the downtown location,” stated the museum in an email to Ha-Shilth-Sa. “This is to maintain accessibility for Indigenous communities throughout the province to visit with belongings and allow space for people to be with them in privacy. There are upcoming sessions this fall with the First Nations Summit and with tribal councils to continue conversations about how best care for the belongings in our care.”

Currently only about one per cent of the museum’s collection is on display. With over seven million artifacts in its care, the construction of a new facility is intended to house the RBCM’s extensive archive, while offering additional space for research and public engagement. With a total estimated cost of $270 million, the collections and research building in Colwood is expected to be open to the public in 2026.

“Visitors will also have the opportunity to see the team working with specimens and artifacts more easily - work that at present, is predominantly behind closed doors,” stated the RBCM.

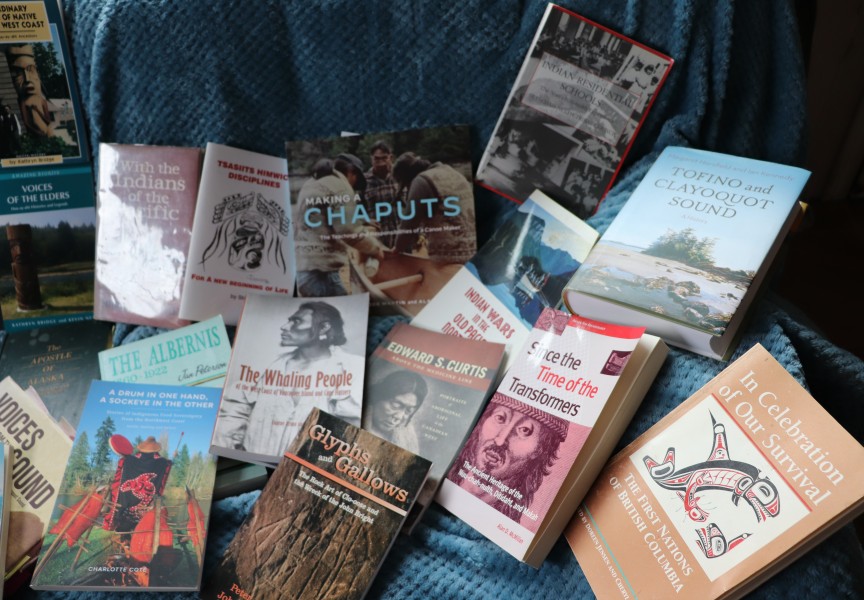

The museum’s Ethnology collection includes over 14,000 objects, spanning from the early 1800s to the present. Much of this is Indigenous to British Columbia, with tools, regalia, basketry, bead work, weaving and wood carving. Sizes range from full-scale canoes and totem poles to miniscule jewelry.

Two of the larger pieces in this collection are a pair of welcome figures that originate from the front of a big house in Kiixin, an ancient Huu-ay-aht fortress and village site in Barkley Sound. The welcome figures can be seen at the museum’s main lobby, while replicas stand on either side of the entrance to the House of Huu-ay-aht in Anacla.

In many cases, the Indigenous artifacts were taken from their original places without permission of the people who lived there, a historical dilemma that has led the RBCM to repatriate pieces to their home communities since the 1970s.

In 2018 the remains of six whalers were returned to Ahousaht, along with bones from two other individuals that were taken from the northern part of Flores Island. For many years, all of the remains were mixed together in a plastic tote container in the RBCM’s storage. The whaler’s remains were originally taken from an Ahousaht whaling shrine in the 1930s by Rev. George Kinney, a missionary stationed in Bamfield who travelled the west coast of Vancouver Island. This collection ended up at the museum after Kinney’s death in 1958, which had the remains of two other people added to it during the following years after bones were found on northern Flores Island protruding from the ground.

The remains were transferred into a cedar box made by Ahousaht artist Wally Thomas for transport and burial in a graveyard on Flores Island, with Ha’wiih and witwaak accompanying the journey back to Ahousaht for security.

“In some repatriation cases, communities have wished for us to retain their belongings but to transfer the ownership back to them, while others have wished for their belongings to be physically returned home,” wrote the museum. “Through ongoing communication, community visits, and open dialog we are working with communities to ensure that their wishes for their belongings are being honoured whether that is through repatriation or other aspects of museum work.”

Another element of the RBCM’s repository is the Indigenous Audiovisual collection, with approximately 65,000 images documenting the province’s First Nations from the 1850s to the present, plus about 200 videotapes of potlatches and other ceremonies.

Also included in this collection are at least 3,700 sound recordings of First Nations people. The orally recorded history of tribes and communities are preserved in these tapes, with traditional dialects spoken by fluent speakers.

“Some of the sound recordings and video tapes can be accessed by appointment; those that document family histories and ceremonies can be accessed only with the permission of the rights holder of the hereditary privileges,” stated the RBCM on its website.

These recordings have recently been discussed during the Nuchatlaht case in the B.C. Supreme Court, where the First Nation is claiming Aboriginal title over the northern half of Nootka Island. The province is disputing that there was a continued history of inland habitation in this area, but the RBCM tapes could be presented as evidence, as the Nuchatlaht’s legal team is prepared to invest in translating and transcribing the recordings if needed.