With the hope of reversing the effects of a “broken system” that has resulted in a growing wave of incarcerations for B.C.’s Indigenous people, two justice centres will soon be opening on Vancouver Island.

Equipped with eight or nine lawyers each as well as other support staff, in the coming weeks the B.C. First Nations Justice Council will be opening regional centres in Victoria and Nanaimo. The justice centres are designed to help Aboriginal clients with criminal and child protection matters through legal advice as well as offering assistance in housing, employment, addictions and mental health.

Besides the Vancouver Island locations, justice centres are also opening this winter in Vancouver, Surrey, and Kelowna.

“The [Indigenous Justice Centres] aim to help Indigenous people involved in the justice system address the causes of their involvement and offer supports to help prevent future interactions with police and the justice system,” stated the BCFNJC in a press release issued Jan. 11.

Four other justice centres have already been opened by the BCFNJC in Chilliwack, Prince Rupert, Prince George and Merritt, with an online centre for all the province that opened during the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to Kory Wilson, chair of the First Nations Justice Council, the centres address “the dire need to correct the harms inflicted by a broken system”.

The burning issue within law enforcement and the courts is the vast overrepresentation of Indigenous people who continue to be charged and incarcerated. Despite comprising 5.9 per cent of British Columbia’s population, Aboriginal people make up 35 per cent of those who are incarcerated provincially, according to BC Corrections.

Released in March 2020 by the justice council and the province, the B.C. First Nations Justice Strategy aimed to change this trend with a list of 43 recommendations. Among the first orders of business were the establishment of 15 justice centres across the province by 2025.

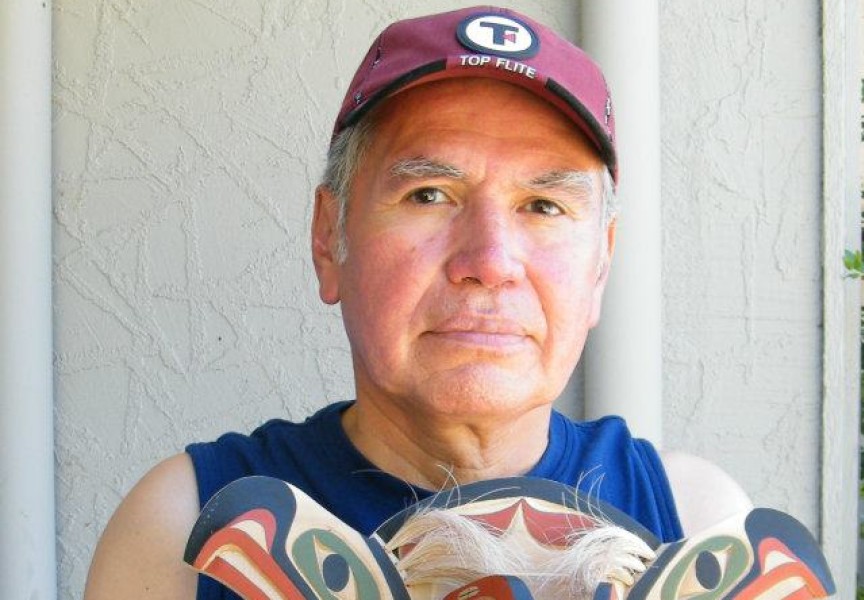

Judith Sayers is president of the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council and serves on the BCFNJC board of directors. She hopes that the new Vancouver Island justice centres will help Nuu-chah-nulth-aht navigate through a system that - for many - has worked against them.

“We’re trying to make them a wraparound kind of service where Nuu-chah-nulth can go and seek legal advice,” said Sayers. “We’re trying to build a police accountability unit, so if someone has a complaint against the police, there’s certain staff that can deal with that.”

“The number of people incarcerated in B.C. is one of the driving forces of the justice council,” she added.

When the justice strategy was released nearly four years ago, it cited that Aboriginal people comprised 32 per cent of B.C.’s custody admissions in 2018 - with youth making up 43 per cent of those in custody or under community supervision. This indicated an increasingly severe trend from the previous decade, when Indigenous people accounted for 22 per cent of those in custody.

Amanda Carling, CEO of the B.C. First Nations Justice Council, sees the cause stretching back to the introduction of Canada’s Indian Act in 1876. This resulted in a host of assimilationist policies that bred a system that fosters “racism, poverty, homelessness, dislocation from community, loss of language and culture, and the disruption of traditional family roles and customs,” she said.

“Until true rights recognition becomes the gold standard and First Nations are empowered to revitalize their inherent legal system and reclaim their languages and cultures, we will continue to face these challenges,” continued Carling.

“There’s still so much healing that needs to take place with people. There’s obviously racism and discrimination with the RCMP,” added Sayers. “We really need a lot more cultural training with the RCMP, getting them to understand better the issues and problems.”

In recent years a handful of interactions between Nuu-chah-nulth people and the police have grabbed headlines, including the case of Jocelyn George, who died in the summer of 2016 after spending most of the previous day and night in a Port Alberni jail cell. The 18-year-old Hesquiaht women was initially picked up by police early morning on June 23, 2016, when she was found barefoot, behaving erratically and delusional, according to RCMP testimony from a coroner’s inquest into her death. George was kept in a cell for most of that day and returned there for the night after it appeared there was nowhere else for her to safely go. But early in the morning on June 24 it appeared that George’s condition had not improved, and was transported to hospital before dying that evening from “drug induced myocarditis” caused by cocaine and methamphetamine, according to the inquest.

The coroner’s inquest concluded with a list of recommendations after assessing the circumstances surrounding George’s death, including the establishment of a “justice centre in Nuu-chah-nulth territory to address the overrepresentation of First Nations people in custody”.

Although Nuu-chah-nulth members were consulted while planning the new regional centres, larger population areas appeared to be more appropriate for the justice council.

“The new regional IJCs that we are just opening were placed in locations where Indigenous people navigate pre-trial and trial processes,” explained Carling. “The factors that played into the decision for each regional IJC location include court catchment area, concentration of crisis and concentration of Indigenous people.”

Over the second half of 2023 the justice council held an open invitation for expressions of interest into where the next five centres will be set up. None were received by Nuu-chah-nulth, said Carling, who is looking farther north on Vancouver Island.

“I think there’s room for cases to be made to have them in smaller centres, as long as it serves a large area,” said Sayers of the next group of justice centres.

“BCFNJC is currently exploring the needs on the north island, recognizing that many Indigenous people are appearing in court in Port Hardy and Campbell River and that more services may be needed further north,” she said, adding that the justice council is exploring how to support programs run by First Nations that deal with sentencing diversion, healing and post-incarceration support.