If you want to save Pacific salmon from extinction, stop logging the forests they rely on for habitat.

This is the approach taken by the Mowachaht/Muchalaht’s Salmon Parks, an initiative that is quickly gaining steam in Nootka Sound, where the First Nation plans to have a significant portion of its territory protected from industrial logging in the coming years. Since getting word of over $15 million in federal funding at the end of October, the project has formed a society led by a seven-member board, including representation from the First Nation’s Council of Chiefs, the Mowachaht/Muchalaht community, band administration as well as three directors from conservation and economic development sectors in the region. The initiative now has five permanent staff, two of whom are Mowachaht/Muchalaht members. Other funding has been secured from a number of conservation groups.

The Salmon Parks project application says that if the status quo continued, all old growth in Mowachaht/Muchalaht territory would be logged in the next 15 years. Without serious intervention, this puts Nootka Sound’s salmon stocks at risk of facing extinction over the next two decades, after 90 per cent of the region’s salmon population has declined since industrial forestry took hold over the past century.

Hereditary Chief Jerry Jack has seen the rivers in his territory dry up over his lifetime, but the full extent of how much the area has been transformed became clear during a flight he took over the past year.

“I never realized how much devastation there was by logging. It’s really sad,” said Jack, noting that although he’s not against forestry harvesting altogether, sustainable practices are needed. “We’re slowly losing everything, and things have to change. The logging practices have to change, because they’re eating our rivers.”

Although he’s just in his 40s, Jamie James recalls a time from his youth when salmon filled a stream running through Ahaminaquus Creek, by a reserve on Muchalaht Inlet where the First Nation once had a village.

“That back river used to be just loaded with chum, all year round,” said James, who is now Mowachaht/Muchalaht’s field logistics coordinator. “Now you don’t see them at all anymore.”

Salmon Parks are now recognized under Mowachaht/Muchalaht law, but they have yet to receive any designation by the Province of British Columbia. Even so, the recently awarded funding will protect almost 39,000 hectares of old growth in the First Nation’s territory, ancient forest that contains “critical salmon ecosystems”, according to the project description. This will halt industrial-scale logging in the Salmon Parks, but smaller operations can continue, such as hunting, fishing and the harvesting of trees for cultural purposes. The Salmon Parks are intended to eventually encompass 66,595 hectares by 2030 – the same year that the province has pledged to have 30 per cent of its land protected.

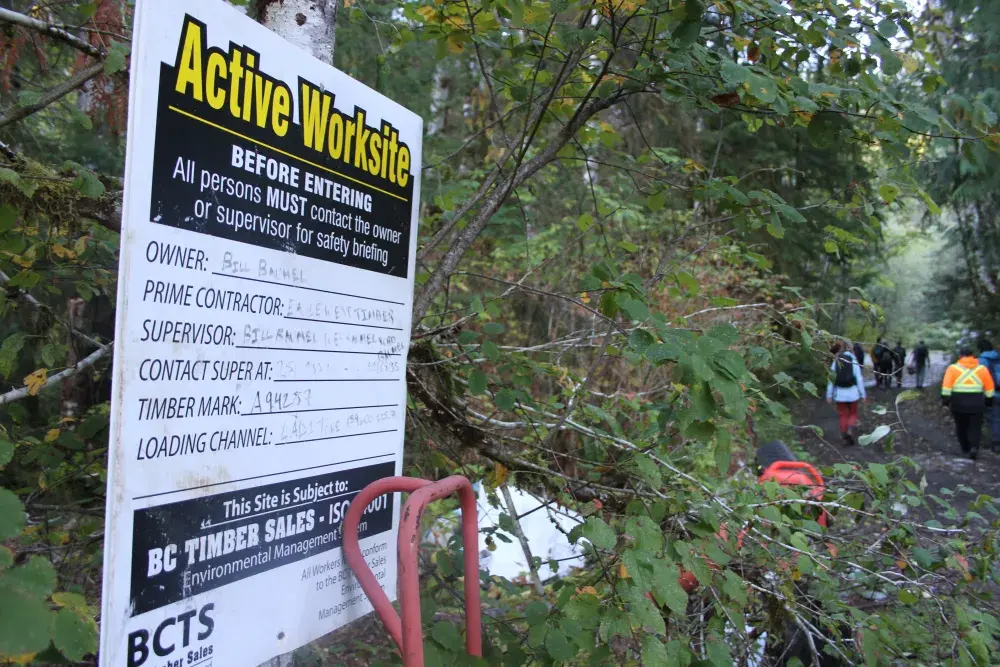

Logging tenures on Crown land in the region are currently held by Western Forest Products and BC Timber Sales. Of the over $15 million recently granted by Environment and Climate Change Canada, almost $12.5 million is allocated for land acquisition costs, notably buying out tenures that are currently held by forestry companies.

“It’s the single most important intervention we can take to help salmon,” said Eric Angel, general manager of the Salmon Parks Stewardship Society. “We can’t really do much about ocean warming, we can’t do much about the climate change impacts…in the big picture, climate change is just something we have to adapt to. But we can absolutely stop cutting down the old growth around those key habitats for salmon spawn, and that will make a huge difference.”

The ’neglected’ importance of old growth

In recent years concerns have intensified about the future of Pacific salmon. In February 2023 the First Nations Fisheries Council of B.C. raised the alarm by announcing a coalition formed to halt the path to extinction, citing that 90 per cent of Pacific salmon stocks have declined since the 1970s.

“I cannot imagine the cultures of the West Coast people without salmon, it would be difficult,” said Hugh Braker, president of the First Nations Fisheries Council, during the coalition announcement a year ago. “We believe that the choices made by British Columbians today will have an effect on the future for the returns of salmon.”

On the west coast of Vancouver Island, several stocks of chinook are listed as “under threat” by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Meanwhile the Tla-o-qui-aht have not allowed their members to harvest sockeye from the Kennedy Lake system since 1992, hoping that the prolonged closure will one day allow salmon to return to a river that once supported commercial fishing.

In June 2021 Fisheries and Oceans Canada announced the Pacific Salmon Strategy Initiative, a $647 million plan to protect and rebuild stocks through improved scientific monitoring, habitat rehabilitation and boosting breeding from hatcheries.

A portion of the PSSI bank is going toward payments to retire commercial fishing licences, thereby thinning the fleet to lessen salmon population losses from harvesting. Licence buyouts are nothing new in B.C., and the commercial fleet has been reduced to roughly half of what it was in the 1970s.

But despite fewer commercial boats on the water and more fishery restrictions, salmon have continued to decline, leading some to wonder if more voluntary retirements will help with the threats that the species continues to face.

“I would have blamed it on overfishing earlier, absolutely, but because hatcheries have increased the fish in the system, you would think there would be more fish,” said James, noting that a major threat to salmon would become more evident if hatcheries ceased to breed fish. “You’d see the fish stocks decline really fast because of logging. There’s no spawning habitat. People think that it’s because of overfishing - it’s the habitat that’s the issue.”

According to the Pacific Salmon Foundation, approximately half of B.C.’s 9,000 wild populations of the species are in some sort of decline. Salmon that spend more time in rivers and lakes appear to be particularly threatened.

“Pretty key parts of the salmon lifecycle are tied to these terrene aquatic landscapes, everything from spawning to the initiation of juveniles really depends on the state of trees surrounding salmon streams,” said Katrina Connors, program director for the PSF’s Salmon Watersheds Program. “Generally, the bigger and older the forest, the better salmon will fare.”

Connors noted that old growth trees are “critical” for healthy salmon ecosystems, including the shade they provide for spawning habitat.

“This is really important for keeping salmon eggs cool. The shade also reduces algae and other plants in the stream, which reduces the amount of oxygen for salmon,” she explained. “These riparian ecosystems, they provide so much for young salmon. The leaves, the needles of plants, they have insects, which fall into the water…the roots from the trees help to stabilize stream banks and slow erosion, which reduces the amount of sediment.”

The State of Canadian Pacific Salmon, which was published by DFO in 2019, details the complex factors that have contributed to the species’ decline, including the effects from a warming climate, ocean heat waves that alter food sources when the salmon migrate out to sea, and rising air temperatures. The department also acknowledges that historic logging has damaged riparian zines next to streams, warming water in the summer, while contemporary forestry can also “contribute to landslides if significant portions of watersheds are cleared or roads are built with poor drainage.”

“Wood and debris from old growth trees plays an important role in shaping the character of smaller coastal stream systems and provides places for fish to live and hide from predators,” wrote the DFO in an email to Ha-Shilth-Sa. “Shade from trees regulates stream temperature during hot weather, providing cooler water that salmon need to reproduce and grow. And mature forests act as sponges that soak up rainwater and feed it back into streams during drier seasons and drought.”

The federal department is involved in a number of projects to help salmon in Nootka Sound, such as exploring restoration strategies like artificial beaver dams that “help moderate water flows in drought-prone systems, promote water storage, and increase water availability through periods of water scarcity.”

But an obvious factor has yet to be attacked, said Angel.

“For quite some time now DFO has really neglected the importance of old growth forest habitat as essential to survival of salmon populations,” he said. “The reason it hasn’t been tackled until now is politically it’s challenging to make it happen, but that’s changing.”

B.C.’s great mistake

In early October 2023 Vancouver Island was still parched from a particularly long, dry summer. Roger Dunlop walked through a park in Gold River, pointing to a moss-covered old growth tree towering over the path.

“When you look at these hemlock trees, like that one, it’s pretty much water. It’s a column of water stretching up into the sky,” said Dunlop, who is the Lands and Natural Resource manager for the Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation. “Every piece of wood that you see laying on the ground here is storing water.”

But this natural system has been disturbed by what the province’s Vancouver Island Land Use Plan calls ‘tree farm licences’, resulting in a patchwork of forest that fails to provide the cohesive ecosystem that salmon need. The Mowachaht/Muchalaht have decided that the wide-ranging protection of Salmon Parks is the necessary solution to British Columbia’s great mistake, said Dunlop.

“We have come to the conclusion that those little band aids on the landscape don’t conserve ecological function,” he said, stressing that what’s needed is “whole watershed preservation to allow those functions to heal. These rivers are like Humpty Dumpty; all the king’s horses and all the king’s men are never going to put these rivers back together again. The only thing that will heal it is the forest.”

Crown land that gets logged is required to be reforested, but the demands of these young trees can create issues by absorbing an unbalanced volume of water.

“There is literature to suggest that once a system has been clearcut or logged, replanted forests are not capable of providing the same sort of hydrologic function as these mature old growth forests for decades,” explained Connors. “Not having clearcutting - or thinning or selecting individual trees for harvest - this can help to minimize the impacts, as well as having a buffer around salmon streams. That’s not always something we see.”

“We’ve created these massive plantations across British Columbia of Douglas fir super trees that are designed to grow faster,” added Dunlop. “But nobody thought that was going to create a water demand and dry up the coho creeks across British Columbia.”

Forestry is often considered the industry that for generations powered development in B.C., sometimes establishing towns overnight around mills located by the deep waters of an inlet - as was the case with Gold River’s establishment in the 1960s.

“In the 50, 60 years since this timber farm licence came into existence in the 1950s there’s been upwards of $6 billion value of trees that have been harvested here. A tiny fraction of that has stayed in the community,” said Angel, adding that most of the area’s forestry jobs go to people who commute into Gold River. “It’s a profoundly extractive economy. It’s an economy that comes in and takes and leaves very little behind.”

According to B.C.’s Ministry of Forests, old growth logging has slowed down in recent years.

“Between 2019 and 2021, an average of 2,707 hectares of old growth was harvested annually from publicly managed lands on Vancouver Island – that’s only 0.3 per cent of the total estimated amount of old growth on Vancouver Island,” stated the ministry in an email to Ha-Shilth-Sa. “By prioritizing sustainability, we will ensure that our oldest and rarest forests are protected, while supporting local, sustainable jobs.”

Furthermore, 2.42 hectares of B.C.’s old growth has been deferred from harvesting since November 2021. That’s in addition to the 3.8 million hectares that were already protected from being logged.

But Angel believes that a more permanent solution is needed, one that Dunlop estimates could take hundreds of years.

“What we’re trying to do with Salmon Parks is lock in those protections so we’ve got that long-term assurance of protection for that habitat,” said Angel. “Old growth ecosystems are salmon ecosystems. They evolved together.”

This story was made possible in part by an award from the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.