Momentum is building to have the Whalers’ Washing House returned to its original site at Yuquot, after the contents of the shrine have sat in a New York museum’s storage for over a century.

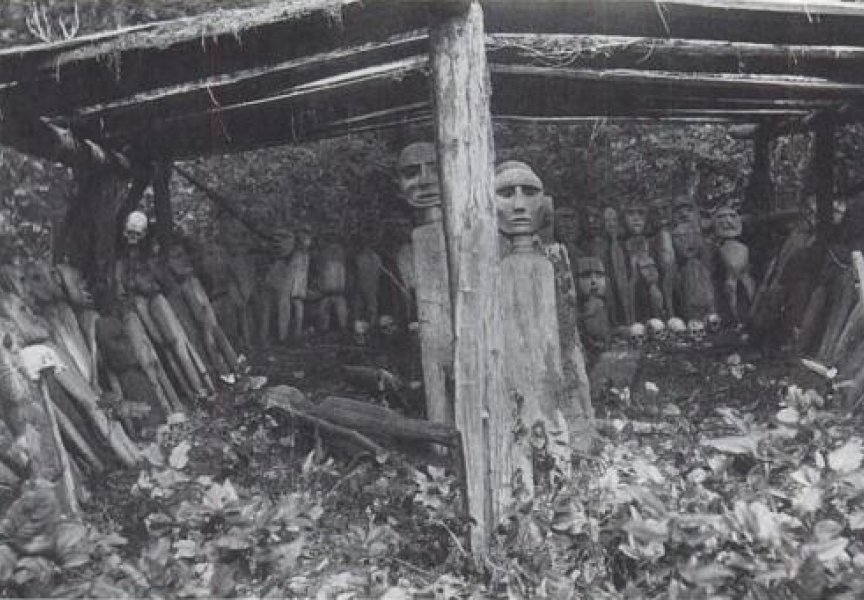

Originally situated in a heavily wooded, unnamed island on Jewitt Lake by the ancient Mowachaht village site of Yuquot, the shrine has been called “the most significant monument associated with Nuu-chah-nulth whaling” in the location’s designation as a National Historic Site of Canada. That national recognition has been in place since 1983, but the Whalers’ Washing House has been absent from its sacred home since 1904, when it was brought to the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

The shrine was purchased – or stolen – depending on one’s interpretation of historical accounts. George Hunt, a Tlingit-Scottish ethnographer, learned about the shrine in the winter of 1900-01. He managed to photograph the site, attracting the interest of anthropologist Franz Boas, who arranged a purchase on behalf of his employer, the AMNH. The deal was made for $500 with two Mowachaht elders – but on the condition that the shrine be removed after the tribe had left Yuquot to hunt seals.

“It was the best thing I ever bought from the Indians,” wrote Hunt to Boas, who both collected many cultural pieces from Indigenous peoples of the B.C. coast.

The shrine’s location could soon change if efforts from a newly formed committee are successful. On July 24 members of the Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation Whaler’s Shrine Repatriation Committee are set to head to New York to meet with the museum’s Cultural Resource Office for a private viewing, when a “ceremonial blessing” will be given for the contents of the shrine.

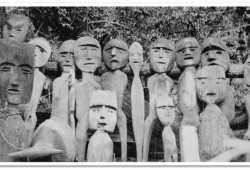

“That’s to just do a chant and a prayer over the human remains,” said committee member Margaretta James, referencing the 16 human skulls that are part of the Whaler’s Washing House. “We formed this committee to actively work on the shrine’s return.”

The shrine also consists of 88 carved human figures and four whale carvings that were once housed in a structure where whalers purified themselves before the hunt by absorbing the power of their ancestors.

“The shrine was where our whalers prayed and practiced ritual oosemich (bathing) to prepare for the physical and spiritual challenges they faced when hunting the world’s largest animals,” states the Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation on its website.

“Such shrines were the sites of purification rituals,” states a submission report sent to the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada in 1983. “These shrines were buildings resembling houses and containing figures of animals and spirits, as well as corpses and skeletons.”

But the location of these sacred places were only known to whaling families, and if a shrine was owned by a chief, no one was permitted to enter or even approach it. This was the case regarding the Whalers’ Washing House.

Mystery around the shrine was still apparent in the late 1980s, when the New York museum approached the Mowachaht/Muchalaht about replicating the Washing House for display.

“A couple of the elders, who have since passed, knew nothing about it because it was such a secret,” said James, who is also president of the Land of Maquinna Cultural Society.

The shrine was a subject in the Washing of Tears, a film about the Mowachaht/Muchalaht people produced by the National Film Board in 1994. In the film members of the First Nation are seen at the AMNH looking over contents of the Whalers’ Washing House, and since then a consistent desire has been present in the Mowachaht/Muchalaht community to have the shrine returned to its original place.

James first saw the shrine’s contents in 1988, something she describes as a “life-changing” experience.

“You just know that you’re in the presence of something far beyond you,” she said. “You could just feel the power of it. We just want to honour that next week.”

Albert Lara will also be heading to New York to see the shrine on July 24. An American veteran who lives in southern California, the 73-year-old recently discovered indications that he could be related to the Mowachaht Tyee through genealogical research.

“He traced his bloodline to a woman that could have been a child that Chief Maquinna sent to California during the fur trade era on one of the ships,” said James. “After he discovered that line he did a lot of reading and research about us, including the shrine issue.”

Lara contacted the First Nation, and his interest reignited the desire to repatriate the shrine, explained James. A formal request to have the shrine returned was sent to the museum by the Mowachaht/Muchalaht, and further discussion ensued between the two parties over the spring.

In the United States the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act actually requires that Indigenous cultural items be returned to their “lineal descendants” by federally funded institutions like museums, although this legislation does not apply to artifacts and remains taken from First Nations north of the border. The AMNH did not respond to Ha-Shilth-Sa’s request for comment about plans to repatriate the Whalers’ Washing House.

James is optimistic that the shrine could be returned as early as the end of this year. Amid its history of being a sacred site only accessible to a select few, no plans for public display have been announced.

“It will be back on the island, but it will be protected somehow,” said James.