Canada’s Indian residential school system existed. The horror stories have been in the news across the nation for decades. Former students, now elders, have publicly shared their painful, intensely personal and often graphic stories.

Yet, there remains a segment of the Canadian population questioning whether Indian residential schools and their legacies are as bad as they are being portrayed. It is called Indian residential school denialism, and a Vancouver Island politician working to shine a light on the issue.

Former Canadian senator Lynn Beyak delivered a controversial speech in the Senate that illustrates what Indian Residential School denialism is. In her speech, she characterised the Canadian Indian residential school system as being “well-intentioned”.

“The Conservative Senator argued that instead of dwelling on the mistreatment and abuse experienced by many of the 150,000 Indigenous children and youth who attended residential schools in Canada between 1883 and 1996, people should focus on all the ‘good’ the schools accomplished in terms of assimilating Indigenous peoples into Canadian society,” according to an article by Sean Carleton published in 2021 on Taylor and Francis Online.

Beyak said it was her intent to speak “in memory” of the “kindly” residential school staff whose “remarkable works” and “good deeds” have gone unrecognized because they are too often “overshadowed by negative reports.”

Initially, Beyak refused to apologize for her position and went on to post racist letters on her official Senate website, letters that describe Indigenous people as lazy and inept and use racial epithets to describe First Nations.

In February 2020, Beyak made an official apology and agreed to take prescribed education and sensitivity training.

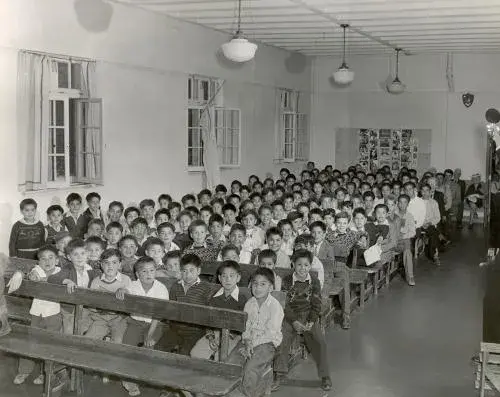

The Indian residential school system was established in the late 19th century as part of the Canadian government's policy of assimilation. The primary goal was to ‘kill the Indian in the child’, eradicating Indigenous languages, cultures, and identities. Over 150,000 Indigenous children were taken from their families and placed in these schools, which were often run by religious organizations.

There are elder Nuu-chah-nulth Indian residential school survivors that know first-hand what abuses were doled out at the institutions, where parents were not allowed to be around to protect their children.

With both federal and provincial governments - and even some municipal governments - making moves to acknowledge its racist past and reconcile with Canada’s First Nations, there remains a segment of the population that deny that damages done are as bad as they are being portrayed.

Indian residential school denialism refers to the discounting or downplaying of the historical and ongoing impacts of the institutional system in Canada.

There is an article about the issue on the website Active History. According to bloggers and historians Sean Carleton, Alan Lester, Adele Perry, and Omeasoo Wahpasiw, Indian residential school deniers do not dispute that the institutions existed and did harm to the children that were there. Instead, “they employ a discourse that twists, distorts, and misrepresents basic facts about residential schooling to shake public confidence in truth and reconciliation efforts, defend guilty and culpable parties, and protect Canada’s colonial status quo.”

The City of Powell River, named after Isreal Wood Powell, is considering changing its name as part of its commitment to reconcile with the local Tla’amin First Nation.

Born 1836 in Port Colborne, Ontario, Israel Wood Powell served as superintendent of the newly formed Department of Indian Affairs for the Province of British Columbia, where he remained until 1889.

During his tenure, Powell pursued policies aimed at assimilating Indigenous Peoples in British Columbia into Euro-Canadian society. One of those policies was the establishment of Indian residential schools, which he viewed as the imperative to educate and “civilize” Indigenous children.

“He supported residential schools to turn Indigenous children into ‘useful members of society’ (Powell’s words). In his annual report in 1882 he wrote to the provincial government encouraging them to establish residential schools in B.C.,” states Know History Historical Services in their report to Tla’amin. “One of Powell’s first actions in office in 1872 was to condemn the Indigenous cultural practice of the potlatch, which he viewed as a major obstacle to the assimilation of Indigenous groups into settler Canadian society.”

In 1884 the federal Indian Act was amended to ban the potlatch. An important instrument of First Nations governance and societal culture, the potlatch ban wasn’t lifted until 1951, directly impacting three generations of Indigenous peoples.

On May 12, 2021 the Tla’amin Executive Council requested the City of Powell River consider a name change in light of the devastating legacy the actions of Israel Powell have had and continues to have on the Tla’amin people. Because of the city’s commitment to reconciliation, the municipality and the Tla’amin Nation have entered into a conversation to explore a possible renaming of the city.

But there has been resistance to the idea of changing the name of the City of Powell River.

Rachel Blaney, NDP MP for North Island-Powell River, invited community members to a gathering in Powell River on Jan. 20, where an estimated 400 attendees discussed the harms of Indian residential school denialism. Joining Blaney is NDP MP Leah Gazan, an educator and human rights advocate.

“The discussion will focus on the ongoing harms caused by Indian residential school denialism, explore its impact on survivors and communities, and discuss actionable ways to advance truth, justice, and reconciliation,” Blaney’s office said in a statement.

“This discussion is about honouring the fact that Indigenous people who have lived through residential schools or are related to survivors of residential schools should not be put in a position where they have to defend that those experiences happened,” said Blaney.

Leah Gazan is a member of Wood Mountain Lakota Nation, located in Saskatchewan, Treaty 4 territory. In 2022 her motion recognizing residential schools as an act of genocide received unanimous consent in the House of Commons.

In September 2024 Gazan introduced Bill C-413, an Act to amend the Criminal Code to criminalize the wilful promotion of hatred against Indigenous peoples by condoning, denying, downplaying or justifying the Indian residential school system in Canada through statements communicated other than in private conversation.

“Residential school denialism jeopardizes the safety and wellbeing of survivors, their families and Indigenous communities,” said Gazan. “It is simply and incitement of hate against Indigenous people, which undermines any progress made towards reconciliation. We need to protect the stories of survivors and ensure denialism is stopped.”

Blaney says that misinformation is getting out to the public and is causing a rise in hate and discrimination towards the Indigenous community. Much of the misinformation comes through social media, self-published books and other means.

“About 400 people attended, which I think really speaks to the interest, and they were a respectful crowd,” said Blaney.

She went on to say that Leah Gazan spoke for about 40 minutes about Bill C-413 and why it is important to protect the stories of Indian residential school survivors.

The proposed bill went through its first reading in the House of Commons on September 26, 2024. With a federal election on the horizon, Blaney cannot say what will happened with it.

“I guess it depends on the outcome of the election,” she told Ha-Shilth-Sa.

Blaney says the meeting was recorded and will be uploaded on her YouTube channel as well as the City of Powell River’s pages.