It became disturbingly clear that even remote First Nation communities can be hit by the rapid spread of COVID-19 when an Alert Bay woman succumbed to the respiratory illness on April 24.

This is the first person in an Aboriginal community to die from coronavirus infection in British Columbia, and the outbreak on Cormorant Island, located east of Port McNeill, has fuelled warnings over the last week from Nuu-chah-nulth leaders on the west coast of Vancouver Island.

In a letter to Huu-ay-aht citizens on April 27, Chief Councillor Robert Dennis Sr. noted that the First Nations Health Authority reported that 57 cases have been tracked in Indigenous communities in B.C., and almost half of these infections are on Vancouver Island. The FNHA would not confirm these numbers, but across the province cases continue to grow in every health region, totalling 2,145 with 33 new infections on Friday, May 1. One hundred and twelve of B.C.’s cases have ended in fatality, while 1,357 of those who were infected are deemed fully recovered.

In his letter to citizens Dennis stressed the need to stay at home and not interact with anyone outside your household, heeding the alarm from the Alert Bay outbreak.

“This is upsetting because it could just as easily happen in Anacla. We are isolated from much of the risk, but if people come in and out of our community there is still a risk,” wrote Dennis. “Our isolation keeps us safe, to some degree, but it also means the risk is far greater if the virus arrives because we do not have the health care services of other communities.”

Ahousaht leaders have been updating members of how the First Nation is responding to the pandemic with daily online addresses. To stress the urgency of practicing measures to limit the spread of COVID-19, on April 28 Ahousaht included ‘Namgis Elected Chief Don Svanvik in the live update via video feed. Since April 18 Alert Bay has been under a local state of emergency, after the village’s mayor Dennis Buchanan contracted the coronavirus despite staying on Cormorant Island during the pandemic.

“We had 26 confirmed cases this morning. Out of that 14 are being recovered,” said Svanvik of his community on Cormorant Island.

“I think that there may have been a feeling that because we are remote that it wouldn’t touch us, but it has come to touch us - we don’t know how, we don’t know when - but what we know is that it’s here,” he added. “There’s only one way to get rid of it, there’s only one way to prevent it, and that’s following the directives of the health experts.”

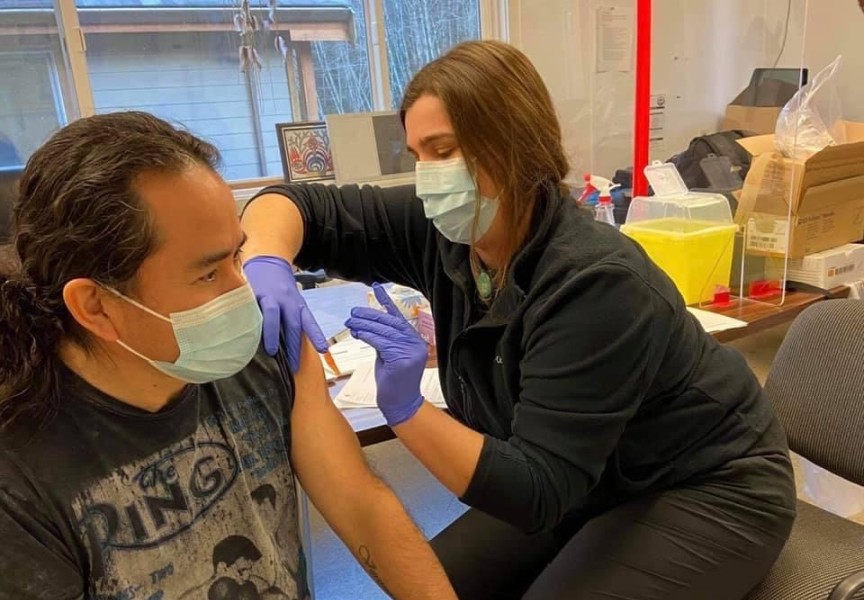

A fundamental part of the directions coming from health authorities has been to avoid contact between people, thereby removing the chance of the coronavirus spreading. This has led health professionals to limit visits to remote communities, instead relying on virtual methods of helping patients.

Dr. Ian Warbrick is currently helping to find ways for Nuu-chah-nulth communities to access health services during the pandemic.

“Even things like wound care that were happening have been held back a bit - but immunizations, home health checks, that can’t be done virtually,” he said. “We’re trying to do everything we can virtually. If we can’t meet a person’s needs virtually, then oftentimes what ends up happening is they’re brought to Tofino or Campbell River or wherever it may be.”

While remote communities have the possible advantage of being affected by COVID-19 later than urban centres, Warbrick cautions that limited local services brings a significant risk of the disease overwhelming whatever medical support is available.

“If a lot of people get sick at once, there’s only so much capacity to transport people,” he said of remote West Coast communities. “There may be a false sense of security, that if we isolate from the outside world, then we don’t necessarily need to self isolate within our community. I wish that was true, but unfortunately it’s just not the case.”

It can take up to two weeks for COVID-19 symptoms to become apparent, but a growing number of studies suggest that transmission is possible before someone begins coughing or shows a fever.

“The horrible thing about this COVID is that it’s asymptomatic for so long, so you just don’t know who’s got it, who’s carrying it,” noted Warbrick, adding that remote communities should prepare to see cases sooner or later as the virus continues to spread. “The way that we’re thinking about it is it will inevitably get to those communities in some point or another. We just hope that when it does that they’re practicing self isolation enough that it spreads slowly.”

Ahousaht has been working to limit the 45-minute boat trips to Tofino by taking grocery orders from households in the Flores Island village. Curtis Dick, manager of Ahousaht’s Emergency Operations Centre, stressed that more can be done to cut back on travel.

“As a province we’re doing really well, but as a community we can do better,” he said during the First Nation’s online address to members. “Stay home when you can, don’t travel. A message to our boat drivers: Don’t overload your boat, don’t load up your boat.”

Meanwhile, a 9:30 p.m. curfew remains in Alert Bay to avoid any possible transmission between households.

“You need to stay home absolutely as much as you can. It’s critical in my house, my children can’t even come to my house,” stressed Svanvik. “We have to absolutely minimize any interaction with all people, because if it’s not in your community now, and nobody leaves and nobody goes there, it’s probably not going to get there. But we don’t even know how it got here.”