Friendship centres, tested as never before, are expecting 2021 will be no less challenging than 2020.

“We’re planning to be in this for the long haul,” said Lesley Varley, executive director of B.C. Association of Aboriginal Friendship Centres (BCAABC). “We expect to be in this pandemic for some time yet.”

One-time COVID-19 funds totalling $7.8 million, announced Dec. 11 by the provincial government, bring an added measure of relief.

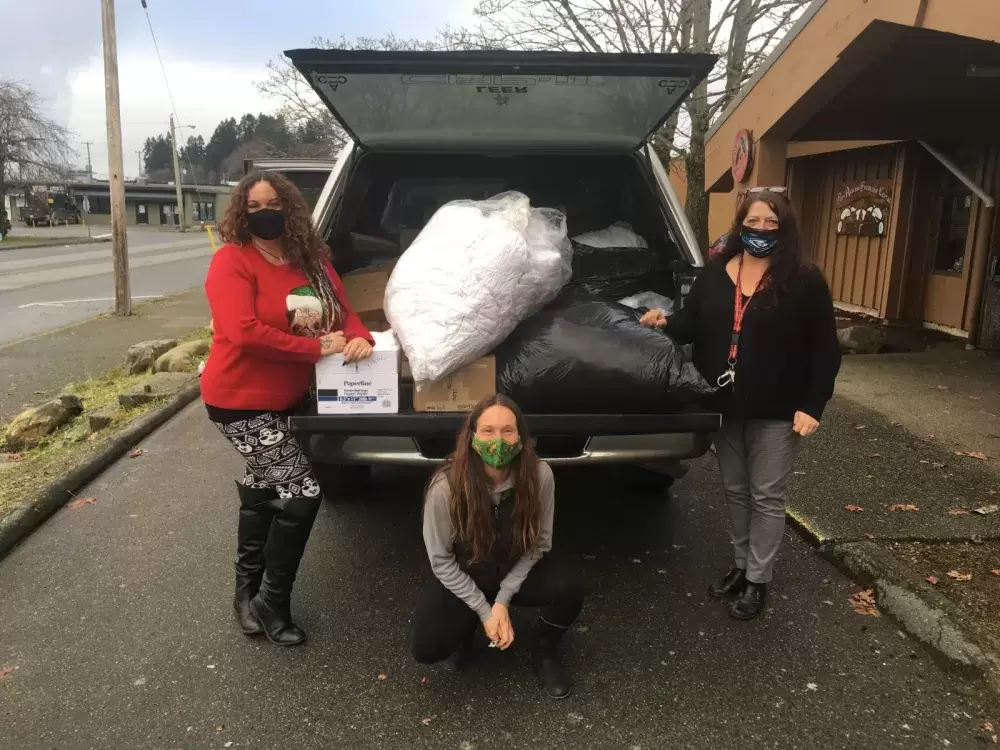

“We are addressing three priorities as a result of COVID-19 — food security, personal protective equipment and sanitation, and equipment and supplies,” Varley said. “The allotted funding will help ensure that those who are most vulnerable to the virus have access to food, and that our staff have the equipment and supplies they need to provide these services safely.”

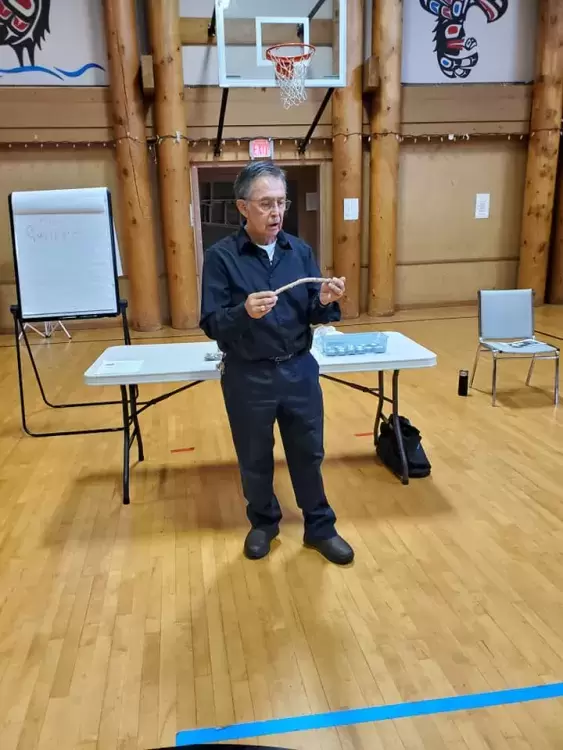

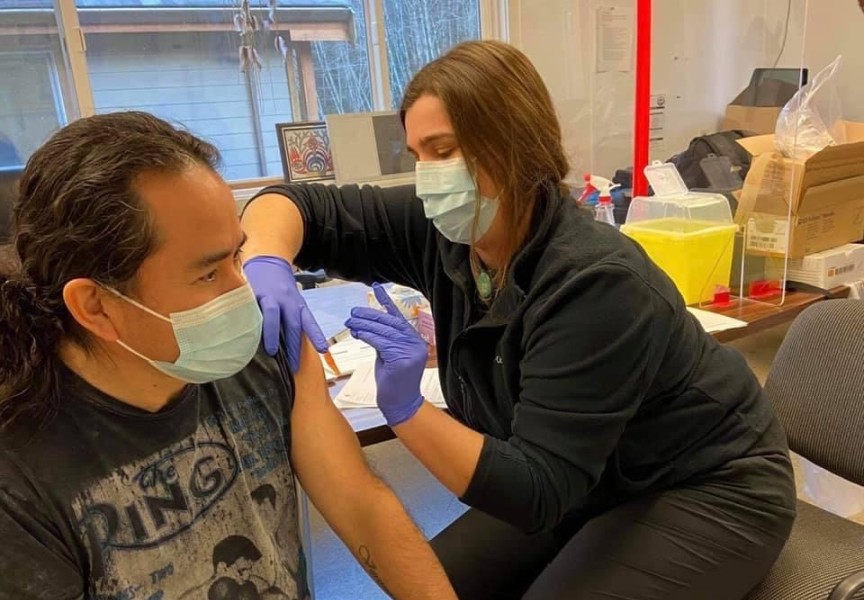

In recent weeks a new role has emerged for the centres, providing clients and elders in particular with information and support for friendship centres as the COVID vaccine rollout expands, Varley said.

The latest funding should help put centres — part of a supportive network of community-based social service organizations — on a firmer footing for a journey that may be far from over.

“Some centres are burning through funding far more quickly than others,” Varley added.

Port Alberni Friendship Centre (PAFC), like so many other social organizations, was confronted with a surge in client needs and additional service demands last spring when the pandemic struck. The centre is a busy hub, normally serving about 80 clients a day on average, and had to respond in a vacuum when other local services were forced to shut down.

“When COVID first happened, everything shut down,” said Cyndi Stevens, executive director of the PAFC. That included the Bread of Life community kitchen, a life line for people already subsisting on little, she added: “Even if they’re not living on couches and they’re at the shelter, it is tough for them. They were possibly the hardest hit when COVID hit. They may have no family.”

People struggling with homelessness and minimal means — between 100 and 140 at any given time in the Alberni Valley — had nowhere to turn. Elders and people with disabilities, who often deal with loneliness on a regular basis, faced greater isolation in the absence of many community supports. Programs requiring personal interaction had to be put on hold temporarily. Uncertainty surrounding the pandemic made it all the more stressful.

PAFC reduced opening hours but didn’t close. Instead, staff looked for ways to adapt, adding online services while maintaining only essential in-person visits. Cultural gatherings and special events as well as parenting, family and youth groups had to be suspended, but staff looked for other means of connecting by phone or social media.

Meanwhile, an even greater and more urgent need as well.

“At the end of March, we started doing hampers and helping the homeless because everything had shut down,” Stevens said.

The centre partners with the Salvation Army to provide 80 food and personal care hampers, enough for 350 people. To comply with pandemic health protocol and reduce risks, particularly for elders, they organized delivery of the hampers as well, ramping up to five days a week.

An immediate hurdle for the centre was funding, especially in the early stages of the pandemic when federal funds were late in arriving. The $30,000 that eventually came through turned out to be a drop in the bucket relative to needs, Stevens said.

Since those difficult early stages of the pandemic, friendship centres have received additional support from a variety of sources, Varley said. Vancouver Foundation donated $1 million and the online commerce platform Shopify gave $450,000 and contacted every friendship centre to identify and fund priority needs.

Using earlier COVID response funds, friendship centres invested in computer tablets. Port Alberni’s purchased 25 and set up its Elder Zoom Camp, Stevens said.

“We’re hoping to get more because it has been really successful,” she said.

Though it can take a while for some to get accustomed to technology, the investment has allowed elders to maintain social contact in the safety of their homes.

“Some of them had tears coming from their eyes when they were first getting onto the system and being able to see other elders,” Stevens said.

Another source of relief, a heat pump to replace the centre’s aging HVAC system — is nearing completion, Stevens said. The new system should make the centre’s gym more comfortable once elders are able to gather again.

PAFC doesn’t have details on the latest COVID funding, but Stevens expects fewer restrictions this time because they are “COVID dollars” expressly for dealing with the pandemic. The grant is directed at supports such as meals and hampers, care packages for seniors and education kits for children. They can also be used to keep staff and clients safe with handwashing stations, sanitization and personal protective equipment.

PAFC’s day care program managed to stay open all along, operating with safe practices in place and on a reduced scale to support essential-service workers.

“Staff have done an amazing job at a point in time when it’s been pretty challenging,” Stevens said. “They’ve supported the children in every way they can.”

A new course at the centre, training early childhood educators, is set to begin in January 2021. The eight-month program will work hand-in-hand with the centre’s day care, allowing participants to obtain their infant/toddler certificate in house.