Those behind a kidney monitoring program for remote communities are hoping First Nations and the province will be ready to ease travel restrictions in the coming months, before more people go undetected in developing a chronic illness.

Early last year the First Nations Health Authority, Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council and Can-Solve CKD Network began a wide-reaching initiative to assess the kidney health of people living in Indigenous communities through blood pressure tests, urine samples, height and weight measurements as well as blood sampling.

“Our goal is to screen communities so that we actually understand both disease and health, because having healthy kidneys and keeping them healthy is just as important as identifying disease early,” said Dr. Adeera Levin, a specialist who heads the Division of Nephrology (kidney studies) at the University of British Columbia.

The intention was to catch those at risk of chronic kidney disease before their condition worsened, but the program was put on hold in March when the COVID-19 pandemic took hold.

Located near the back just below the ribs, kidneys serve a critical function in the body by filtering waste and excess fluid from the blood, converting this to urine for excretion. Chronic kidney disease causes the loss of this function, allowing dangerous levels of fluid, electrolytes and waste to build up in the body. In its final stage the condition can only be treated by transplant or dialysis – but the challenging dynamic of the disease is that it can progress without showing symptoms until the late stages.

“The kidneys are pretty resilient,” explained Dr. Levin. “These organs are really good at adapting. You can get a fair amount of scarring and a fair amount of loss of kidney function before you have symptoms.”

Ten months into the pandemic and its associated restrictions on personal contact and travel, a concern is growing that people could be developing chronic kidney disease without getting the medical attention they need. One in 10 Canadians are at risk, but this rises to 25-30 per cent for Indigenous people – with higher rates in remote communities.

Up to half of diabetics will have signs of kidney damage in their lifetime, but age, smoking, elevated blood pressure, a high salt diet and consumption of processed foods can be factors as well. Levin stressed the importance of working closely with First Nations communities to better monitor those at risk of developing chronic kidney disease. But travelling to remote communities will be not be an option for the time being, as these appointments aren’t deemed essential reason for travel, she said.

Meanwhile, those with compromised kidney function are more vulnerable to become very sick if infected with COVID-19.

“It you’re on dialysis you’re also at higher risk of getting sick if you get COVID, and probably at higher risk of getting really sick,” said Levin.

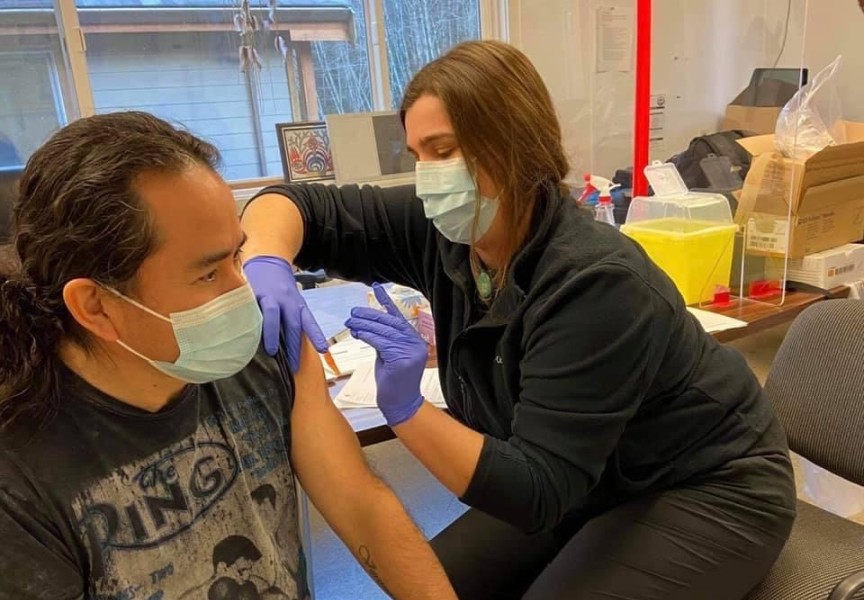

Dr. Kelsey Louie, a medical officer with the First Nations Health Authority, hopes that the kidney screenings can resume this year if vaccinations continue in remote communities and the rate of coronavirus infection drops. The suspension of the monitoring program is part of a larger “disruption in people’s care” due to the medical system’s emphasis on controlling the spread of COVID-19.

“Being told to isolate, being told to not travel unnecessarily, all of these things that came into the world became quite confusing for both health-care providers and for community members,” he said. “Every now and then I’m going to find someone who has a new diagnosis of something. Just because they came through my door I was able to check them and we discovered something new.”

During the pandemic Dr. Louie has incorporated virtual appointments into his practice to monitor patients’ health, organizing the necessary blood work and referrals through online technology.

But even after pandemic restrictions are lifted, the need will remain to foster more trust in the health- care system for the many Indigenous patients who still carry negative associations.

“We often find people only engage when they become very, very sick,” said Louie. “If you don’t have real physical symptoms of, say kidney disease, you’re not going to go get checked out – particularly if you don’t feel comfortable going to a physician’s office or going to a hospital because you had a bad experience.”

Building more trust can come down to what is being communicated to the patient, added Dr. Levin.

“A lot of our Indigenous patients and physician partners tell us, ‘Please don’t keep telling us how sick we are, tell us also how well we are’,” she said.