After over a decade of documenting B.C.’s last remaining old-growth ecosystems, TJ Watt said he hadn’t come across anything quite like the grove of red cedars hidden in the upper reaches of the Caycuse watershed, near Port Renfrew.

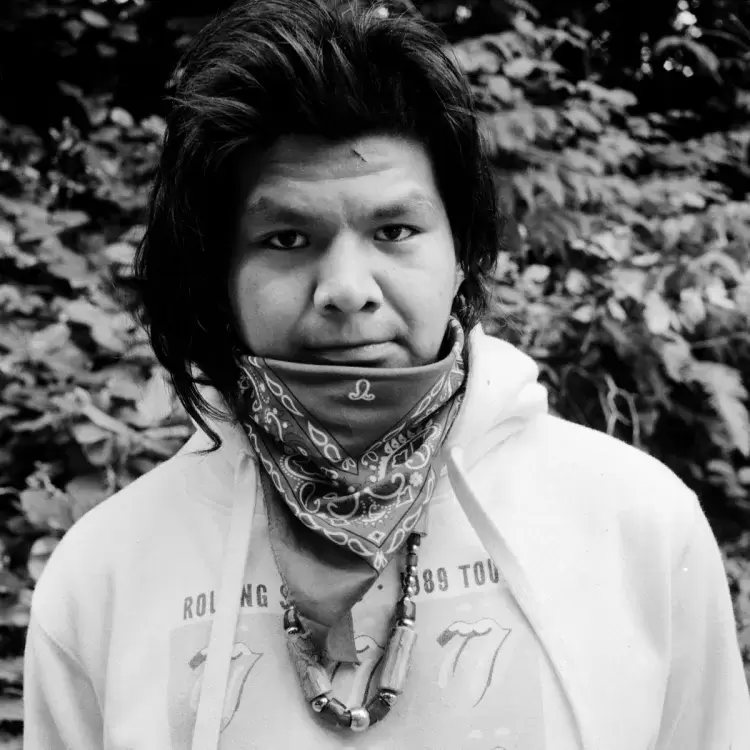

“It was truthfully one of the most stunning old-growth forests I’ve been in,” said the co-founder of the Ancient Forest Alliance. “The sheer volume of giant cedars was mind-blowing – every direction you looked was another 10 to 12-foot-wide ancient cedar that could be 800 years old, or older.”

When he returned later that year in 2020, only their stumps remained.

The now clear-cut grove is located in Tree Farm License 46, which is held by forestry company Teal-Jones.

Watt said he never saw another soul out there until recently, as anti-logging protests have been underway since last August.

“It’s such an obscure spot at the end of the road,” he said. “These places are so special and you wish the world could see them, but how do you get everybody out there? Now, it’s packed.”

‘Third-party activism’

The Rainforest Flying Squad, an old-growth activist group, have been stationed at various blockades throughout the Caycuse and Fairy Creek watersheds since August to prevent Teal-Jones from accessing what they consider the last remaining old-growth forests untouched by industrial logging.

On May 17, RCMP moved into the area to enforce a B.C. Supreme Court injunction that ruled their blockades are illegal. As of June 1, 142 people have been arrested.

The Fairy Creek watershed sits within Pacheedaht First Nation’s traditional territory.

In a statement signed by Pacheedaht Hereditary Chief Frank Queesto Jones and Elected Chief Jeff Jones, the nation said it’s concerned about the increasing polarization over forestry activities in their territory.

“Pacheedaht has always harvested and managed our forestry resources, including old-growth cedar, for cultural, ceremonial, domestic and economic purposes,” read the statement released April 12. “All parties need to respect that it is up to Pacheedaht people to determine how our forestry resources will be used. We do not welcome or support unsolicited involvement or interference by others in our territory, including third-party activism.”

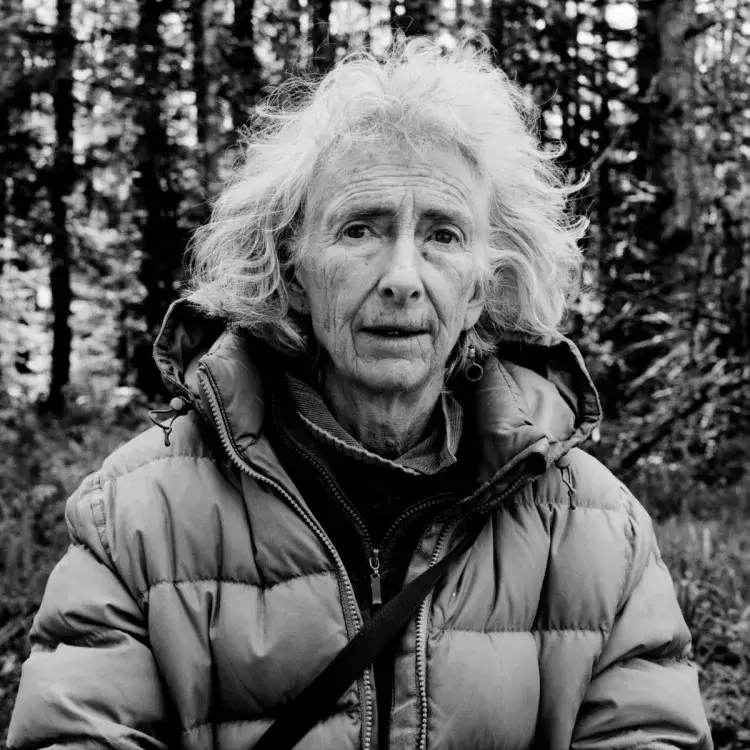

Garry Merkel, B.C.’s old-growth strategic review panel expert and member of the Tahltan Nation, said that, until recently, First Nations communities have been “sitting on the outside looking in.”

“Government recently made a move to re-allocate tenure and get First Nations much more involved in actually owning tenure,” he said. “The problem is, we are very old-growth dependent right now in our forest sector.”

It’s estimated that B.C. will need old-growth logging for another 5 to 20 years, depending on the area, to make the transition to second growth, explained Merkel.

“We just don't have enough yet to make the sector transition,” he said. “That means that many First Nations have come into [the industry] at a time where there is this high dependence on the last remaining old-growth.”

And because many First Nations tenures are dependent on old-growth logging, Merkel said “they are caught in the middle of this thing, with their own communities and with other people.”

Many members of the Pacheedaht First Nation have rallied in support of the protests, including elder Bill Jones, who said he’s fighting for “the last of it.”

“It will be all gone if [Teal-Jones] is given free reign,” he said.

Jones’ nephew, Patrick, joined protestors in the Fairy Creek watershed in May. The 23-year-old said First Nations' self-governance is based on a colonial idea, which entails chief and council making the major decisions for everybody else, thereby seeing the biggest benefits.

Last summer, B.C.’s provincial government appointed foresters Merkel and Al Gorley as an independent panel to consult with thousands of British Columbians about how to manage old-growth forests.

They outlined 14 recommendations that the B.C. NDP promised to implement during the provincial election campaign last fall.

One of the recommendations was the immediate deferral of harvesting from ecosystems that are at “very high and near-term risk of irreversible biodiversity loss.” Over a year later, the province has not made it clear how they plan to implement the deferral, or what constitutes high-risk.

There still isn’t a good definition of old-growth, explained Merkel. In other words, what constitutes old-growth is fluid based on who you’re talking to.

In hindsight, Merkel said he wished they wrote the recommendations more “stringently.”

“But you know, hindsight is always 2020,” he said. “Nobody's gone through this scale of transformation in this province – ever.”

Setting forests back thousands of years

Instead of talking about old-growth forests, Merkel suggested that we should be speaking about old-growth ecosystems. For thousands of years, plants, fungi and waterways have primed the earth to allow cedar trees to grow up upwards of 10-feet in diameter, he said.

If harvested delicately so that the ecosystem’s attributes, structure and function remain intact, you can have very little effect on the ecosystem, he said.

“But the standard systems that we use are primarily clear-cut,” he said. “Sometimes, we even burn [the clear-cuts] afterwards or get rid of all the slash. That sets the ecosystem back potentially thousands of years – minimally, hundreds and hundreds [of years]. It took all of that time for those ecosystems to become what they are with the factors that shaped them in the past. The factors that they're going to face in the next hundreds, if not thousands of years are going to be very different with things like climate change and other human impacts. So, to think they're renewable is simply not true. All those old ecosystems are not renewable.”

Resource Works, a non-profit research and advocacy organization focused on promoting responsible resource development in B.C., released a new report aimed at responding to the “rhetoric coming out of Fairy Creek.”

"The fact is, forest management in B.C. is not in crisis – far from it,” read the report. “Rather, there is a 'crisis' of misinformation.”

Old forest is defined as being 250 years or older and makes up 860,000 hectares of Vancouver Island. Of that, 520,000 hectares, or 62 per cent, is protected, read the report.

“While we welcome the coming paradigm shift in forest management that has been signalled by the provincial government, residents of B.C. can share our confidence that this is being managed in a proper professional and consultative context," said Stewart Muir, co-author of the report and Resource Works executive director.

Conversely, recent mapping done by the Wilderness Committee indicates that old-growth logging approvals have gone up 43 per cent since the B.C. government received the old-growth review recommendations in 2020.

“The government is not keeping its word,” said Torrance Coste, Wilderness Committee campaign director. “We're calling on the government to defer old-growth logging and provide support for communities that currently derive benefits from old-growth … to just say that we need to change the way we're managing old-growth, but not actually changing anything on the ground, leads these companies to go and get it while they can.”

The Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development said it does not feel the Wilderness Committee’s analysis accurately reflects what is happening in B.C.’s old-growth forests.

Following a five-year analysis from April 20, 2016 to April 26, 2021, the ministry said the approved cut-blocks within old-growth areas has decreased by one per cent.

“Several of the conclusions that the Wilderness Committee reached involve overlapping areas, resulting in counting approved cut-blocks within old-growth areas twice,” said the ministry.

“The fact is, 10 million hectares of old-growth is already protected and since coming into office our government has protected hundreds of thousands more,” the ministry noted in a release. “We are committed to work with the committee to better understand their results and to provide a true account of our old-growth forest.”

Soaring lumber prices

Soaring lumber prices in B.C. and across Canada have only added to the tension.

As of May 21, a SPF (spruce, pine and fir) two-by-four cost $1,640 per thousand board feet, while the annual average in 2019 was $372, according to the ministry.

“The price for lumber is just off the charts,” said B.C. premier John Horgan during a media conference on March 17. “We still have a significant amount of work to do in the forest industry.”

Horgan said the province needs to move from high-volume harvesting and focus on the long term.

“These prices will encourage companies to continue to harvest at unsustainable rates,” he said. “Perhaps to catch on to these extraordinary prices.”

To prevent access to an old-growth grove in the Gordon River Valley, the Rainforest Flying Squad erected the Eden Camp, near Port Renfrew.

There are no roads or cutting permits currently issued in the Eden Grove area and harvesting is not permitted, as it is a wildlife habitat area for Northern Goshawk, according to the ministry.

“[Eden Gove] is one of the best of the last unprotected valley-bottom old-growth forests in that region,” said Watt. “The grove itself is not under imminent threat … although the area has been surveyed for logging.”

The grove has become a flash-point because “people are saying, ‘When is enough enough?’” explained Watt.

"We're down to such low-digit numbers of how much of that productive old-growth forest remains, that when the government kicks the can down the road – another year, another two years – industry takes advantage of that and races in to cut the best of what's left,” he said.

In a statement, Teal-Jones vice president Gerry Kotze said the company’s plans at Fairy Creek have been “mischaracterized.”

Most of the watershed is unavailable for logging within Teal-Jones’ tenure, he added.

“We are planning to harvest only a small area, up at the head of the watershed well away from Fairy Lake and the San Juan River,” Kotze said.

2,000 gather in protest

The anti-logging protests on southern Vancouver Island have been likened to the War in the Woods, when around 12,000 people participated in anti-logging blockades to prevent forestry company Macmillan Bloedel from clear-cutting in the Clayoquot Sound. It came to a head in 1993, when 300 people were arrested and became one of the largest acts of mass civil disobedience in Canadian history. In 2000, Clayoquot Sound was designated as a Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO.

Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation Chief Councillor Moses Martin, who was also the elected chief during the War in the Woods, said it’s an entirely different situation.

“In my own case, I had the support of the whole region,” said Martin. “Not just us as Tla-o-qui-aht, but the municipality of Tofino.”

For Martin, the loss of trees on Meares Island meant the loss of the watershed, which Tofino draws its drinking water from.

“That’s so important to all of us that live in this part of the world,” he said.

Despite continued RCMP enforcement, the Fairy Creek protests have shown no sign of slowing down. Last weekend, the Rainforest Flying Squad reported that over 2,000 people gathered within the watershed to support the anti-logging blockades.

British Columbia was built on logging and is “part of who we are at our core – our cultural being as people,” said Merkel.

But as societal values shift, he said “conflict is inevitable.”

“I think our expectations have risen in terms of what we think is possible,” he said.

Just like the protests, Watt continues to preserve old-growth ecosystems through photographs because often, “they disappear without anyone really knowing they existed,” he said.

The Caycuse watershed is just one example of what’s playing out across the province, he added.

“People have taken it upon themselves to literally stand in the way,” said Watt. “If the government was to follow the old-growth review panel's report as it was laid out, there should be immediate deferrals in those most high-risk areas while you figure out the plan for the future of old-growth forests – not after the fact. If they don't exist, you can't do anything about them.”