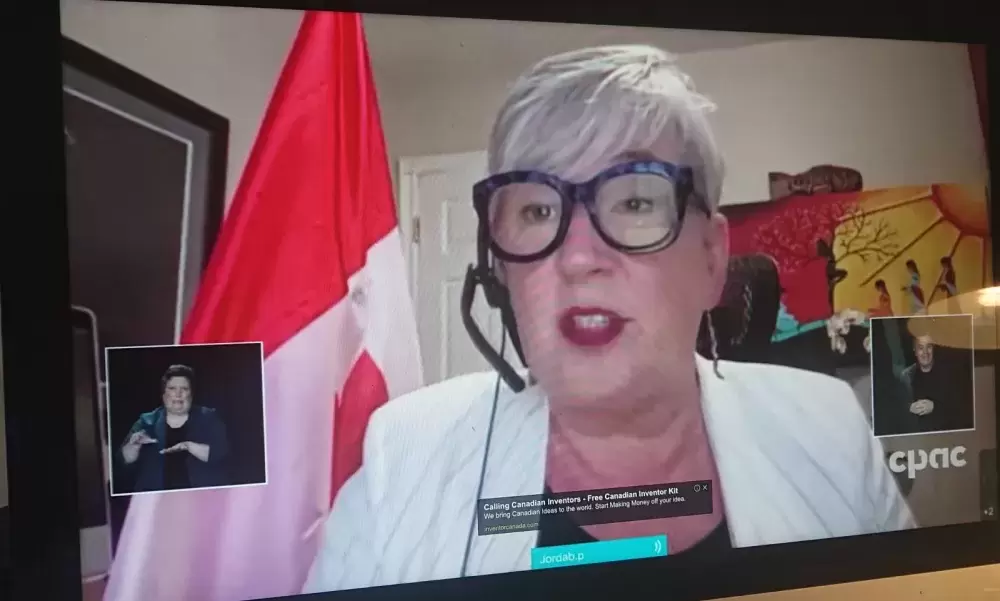

Federal Fisheries Minister Bernadette Jordan used World Oceans Day, June 8, to introduce via Zoom “the largest, most transformative investment in salmon by any government in history.”

“Many Pacific wild salmon are on the verge of collapse, and we need to take bold ambitious action now if we are to reverse the trend and give them a fighting chance at survival,” Jordan said, announcing the Pacific Salmon Strategic Initiative (PSSI).

The $647-million program intends to guide investments and action in four key areas: conservation and stewardship, enhanced hatchery production, harvest transformation, and integrated management and collaboration.

Jordan said the strategy is not a new report or a new study, but “ready-to-go funding that will lead to comprehensive effort to reach a single goal: to stop the decline of Pacific salmon now and to help rebuild populations in the longer term.”

PSSI includes additional federal contribution of $100 million to the B.C. Salmon Restoration and Innovation Fund (BCSRIF), an existing partnership with the provincial government.

“We will be working closely with Indigenous communities, harvesters, recreational fishers, industry, environmental organizations, and provincial and territorial partners to advance actions under each pillar, to stabilize the species and to support a more modern, sustainable and resilient sector,” Jordan stressed.

Out west, the announcement was welcome news amidst a continuing salmon crisis on the Fraser River and declining stocks along the coast. Similar bold pronouncements have been heard in the past, so they tend to be greeted with a degree of skepticism among stakeholders.

Nuu-chah-nulth nations have for years had hopes raised of rebuilding their fisheries through a greater say in management and allocation of wild salmon, only to see those ambitions stymied by what many consider federal fisheries mismanagement and top-down bureaucratic decision-making.

No one doubts the minister’s word on the seriousness of the situation, though. Pacific salmon have never been as imperiled as they are now for a whole host of reasons, climate change and habitat degradation prominent among them.

Would this initiative be any different? Could it be transformative?

“I’m wanting to be hopeful and not worried that things still aren’t going to change,” said Eric Angel, Uu-a-thluk fisheries program manager, sounding a cautiously optimistic note.

The Council of Ha’wiih Forum on Fisheries met with PSSI Senior Director Sarah Murdoch last week after Jordan’s announcement. Murdoch has worked directly with Uu-a-thluk in the past on the federal wild salmon policy and the two have a good working relationship, Angel said.

Murdoch echoed the minister’s emphasis on collaboration, direct communication and working together to determine the most effective use of funding as the new program takes shape.

“She was telling us it’s a short path to the minister, which is important,” Angel said.

The council stressed that Nuu-chah-nulth nations want to be part of the conversation before DFO decides how the initiative is going to work.

“The real concern we’ve got is that they’ve already decided what they want to do and how they want to do it,” Angel said.

Jordan likened the challenges in rebuilding Pacific salmon to the barrier at Big Bar Slide on the Fraser River — “enormous but not insurmountable.”

When she visited the site of the natural disaster last year, Jordan saw the challenge, yet she also drew inspiration from the tripartite response of federal, provincial and First Nations governments.

“There is no quick fix and no one single solution to save this species,” she added. “The salmon must be a priority right across the region for years come … this will require patience and all hands on deck.”

She held out the promise of multi-government cooperation along with conservation stewardship, a federal Pacific Salmon Secretariat, and a restoration centre of expertise for Pacific salmon.

The minister also mentioned investment in new hatcheries, a concern for anyone focused on rebuilding wild stocks. Jordan acknowledged those concerns, however.

“They need to support populations, but not take over,” she said.

Additional hatchery production on Vancouver Island’s west coast — where there is scarcely a stock that isn’t in trouble — isn’t always welcome. While some Nuu-chah-nulth nations want to increase hatchery production in a small-scale, targeted fashion, the overall danger is relying too heavily on them and not addressing the problems hatcheries cause for wild salmon, explained Angel.

“From a Nuu-chah-nulth point of view, each stock is distinct,” Angel said. “We need to be preserving that diversity.”

“NTC and its fisheries department have been trying to get across to government the need to take advantage of regional decision-making processes and knowledge,” Angel said.

That already exists through the west coast salmon roundtables where First Nations sit across from resource stakeholders, he added.

“We all work together to figure how to stem the decline of wild salmon and rebuild habitat,” Angel said.

“We’ve had enough studies; we know what is wrong and what needs to be done. A lot of it is having the political will to tackle some difficult decisions,” he added, hoping for action, not two more years of engagement.

More details on PSSI are expected at technical discussions between Uu-a-thluk and DFO in the fall.

“Unquestionably it’s a very important announcement, and it could be transformative, and we’ll do our best to ensure that it is,” Angel said.

After joining his cabinet colleague for last week’s announcement, former fisheries minister Jonathan Wilkinson, now federal minister of Environment and Climate Change, painted a broader picture of the salmon crisis. Salmon are fundamental to identity and Indigenous peoples, a keystone species supporting many other species as well as humans, he said.

“Salmon may also be the 21st century’s canary in the coal mines when it comes to climate change,” he said.