As the death toll from B.C.’s overdose crisis continues, those who work closely with First Nations are urging people to look beyond the disturbing numbers and into the complexities of treating drug addiction.

On Aug. 31 the B.C. Coroners Service reported 1,011 deaths due to illicit drug use over the first six months of the year, making overdose the leading cause of death for adults under 40, with eighty per cent of these fatalities affecting males. Fentanyl was detected in 85 per cent of the cases, with cocaine methamphetamine and etizolam present in a significant number of deaths.

First Nations people have been affected by the crisis on a scale several times that of the general population. For last year, the First Nations Health Authority reported a fatality rate 5.3 times greater than others in B.C., a 119 per cent increase in overdose deaths over 2019, pointing to the hazards of the COVID-19 pandemic on those who use illicit drugs.

“Poisoned drugs are circulating,” warned Sheila Malcolmson, B.C.’s minister of Mental Health and Addictions. “More people are dying from inhaling illicit drugs than injecting, so please be careful.”

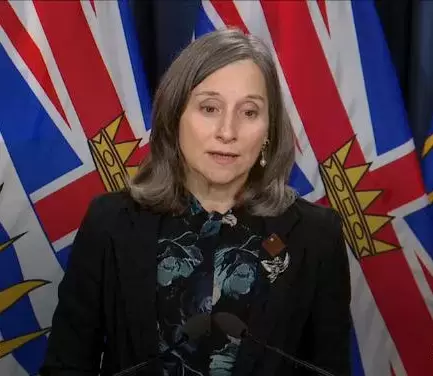

When the numbers were announced for the first half of 2021, Chief Coroner Lisa Lapointe stressed the need for a “wide scale response.”

“This includes removing barriers to safe supply, ensuring timely access to evidence-based affordable treatment and providing those experiencing problematic substance use with compassionate and viable options to reduce risks and save lives.”

The recognition of substance use as a disorder requiring treatment, rather than criminal activity in need of enforcement, has guided a shift in government policy. B.C. is working on decriminalizing possession of illicit drugs with an application to Ottawa for an exemption from Section 56 of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. Meanwhile the Solicitor General sent a letter to police chiefs asking authorities to “focus on more serious crimes and align with more harm reduction principles,” according to the Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions.

A new emphasis has also been placed on prescribing less harmful alternatives to replace street drugs, something that registered nurses and registered psychiatric nurses can now offer with the appropriate training. By June the number of doctors in B.C. who offer opioid agonist treatment increased to 1,671, with a 475 per cent increase in hydromorphone prescriptions over a year.

But this is not necessarily reaching those who need the help most, cautions Mariah Charleson, vice-president of the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council.

“We know it’s very difficult for marginalized people to even have a physician, to even see a physician,” she commented. “There’s one individual in Port Alberni, they’re banned from drug dealers. So they give their money to other people to go get the drugs and it leads to all sorts of things.”

“For people who use substances, accessing opioid agonist therapy, or prescribed opioid alternatives (‘safer supply’) – this is particularly a challenge in rural/remote/isolated communities where getting to a prescriber and then being able to access prescriptions in a timely, regular manner can be challenging,” noted Dr. Nel Wieman, the FNHA’s senior medical officer, in an email to Ha-Shilth-Sa.

While the First Nations Health Authority is working to get more nurses trained to prescribe safer opioid alternatives, a historic distrust of the health care system among many Aboriginal people remains a concern. In November the long-standing affects of negative experiences in hospitals and with doctors was highlighted by In Plain Sight, a report from an independent investigation commissioned by the Ministry of Health.

“We can’t ignore the role that racism and a lack of cultural safety in health/medical services plays,” said Wieman. “[T]here is also significant stigma in play for people who use substances – so all of these create an unsafe, unwelcoming environment that people are reluctant to access in the first place out of fear for how they will be treated.”

As B.C.’s health authorities grapple with a rate of five overdose fatalities a day, Wieman stressed that the affects of trauma on First Nations people cannot be understated. Causes range from residential schools and the Sixties Scoop to evacuations due to wildfires and intimate partner violence.

“When people are living with trauma/intergenerational trauma, they are distressed – and sometimes people make choices to reduce that distress that involve using substances – substances change how we feel,” explained Wieman. “Unfortunately, with the increased toxicity of the illicit/ ‘street’ drug supply, the contamination of the current drug supply makes it increasingly lethal.”

The province has reported that measures imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic have disrupted the normal pathways of illicit drugs, causing dealers to increase the toxicity of what can be bought on the street. This dynamic has brought fatalities to communities across the province, despite their remoteness.

Charleson spoke of two overdose deaths in Hot Springs Cove over the pandemic.

“Hot Springs Cove is a community of less than 60 people,” she said. “Everybody knows each other, everybody plays an integral role in that community.”

“We need to remember that those who have been lost to the toxic drug crisis are our family, our loved ones – they are deeply missed,” said Wieman.

“We’ve lost people who aren’t homeless, who aren’t visually addicts, who are simply members of the community,” added Charleson.