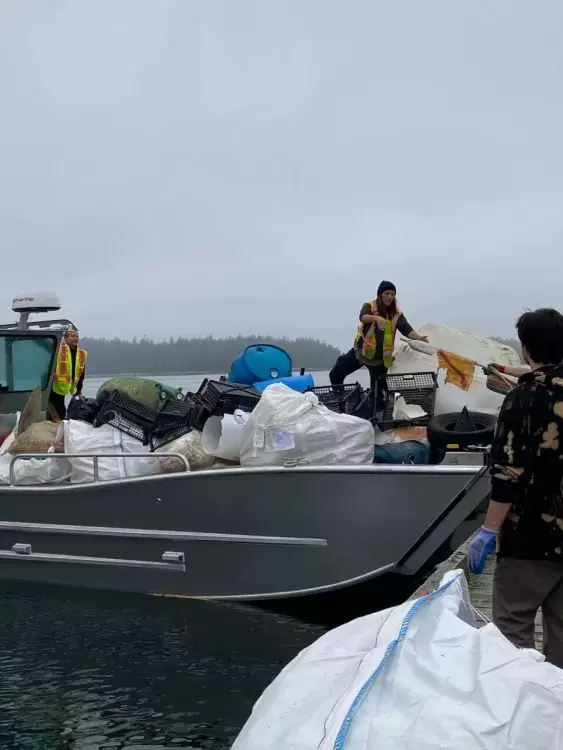

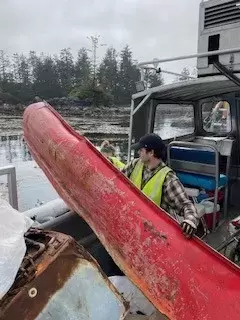

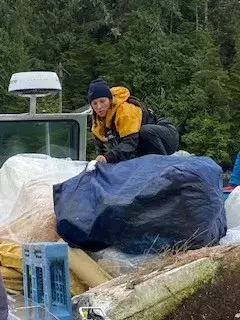

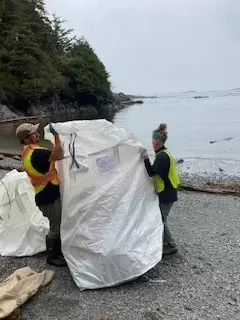

For five days, Rachelle Packwood removed mounds of Styrofoam, rope and tires that had collected along the remote shorelines of the Broken Group Islands in Barkley Sound.

It was the first beach clean-up Packwood had participated in and she hasn’t stopped talking about it since.

“I feel really good about what we did,” she said. “Knowing how many tons of debris we took off that Broken Group is astounding. I have a sense of pride.”

The initiative was part of the West Coast Vancouver Island Coastal Improvement Project, which aims to support large-scale marine shoreline clean-ups and derelict vessel removals along British Columbia’s coastline.

Supported by the provincial government through the Clean Coast, Clean Waters Initiative Fund, the $2.5 million project is managed by the Coastal Restoration Society (CRS), in partnership with Surfrider Foundation Pacific Rim, Rugged Coast, Ocean Legacy, and the T’Sou-ke Nation. Ten First Nations, including Hesquiaht, Ahousaht, Tseshaht, and Ka:'yu:'k't'h'/Che:k:tles7et'h', are also participating in the project.

“Marine clean-up programs are a critical part of reducing pollution in these sensitive ecosystems and protecting fish and other marine life, as well as important food sources,” said George Heyman, minister of Environment and Climate Change Strategy, in a release. “These projects will remove tonnes of debris, create new jobs and provide much-needed support to local governments, Indigenous communities and other groups to address marine pollution.”

Alys Hoyland is the Surfrider Pacific Rim youth coordinator and said that the nations’ involvement was “absolutely crucial to do this work well.”

The nations bring knowledge of the historical and the cultural sensitivities of each site, she said.

“It's such an honour and privilege to learn from the beach keepers that we were working with from Tseshaht,” said Hoyland. “And to use that knowledge to do the work in the right way.”

Four other Tseshaht members participated in the clean up, including Packwood’s son, Jayden.

The 23-year-old said he hadn’t visited his traditional homelands since he was eight years old and that it felt “amazing” to finally return.

“I realized how beautiful it was and it made me want to go back again,” he said.

By the end of the five days, Jayden said he was “exhausted,” but “fulfilled.”

Hannah Gentes is the CRS Indigenous initiatives coordinator and said it’s important for the nations to have sovereignty over the work that’s being done in their traditional territories.

“It's really powerful to have the descendants of the original stewards of these lands come out and do some modern modes of stewardship,” she said. “It’s a really beautiful opportunity for community members to get together and be on the land together.”

Over 90 tonnes of debris have been removed from the coast between the Brooks Peninsula and the Broken Group Islands this summer – and the project isn’t over yet, said Hoyland.

“It’s the biggest clean-up that we’ve ever seen on this coast,” she said. “Getting the plastic out of water and off the beaches gives immediate and short-term relief to those ecosystems. But mostly, it's important for data collection. We need to know what's polluting our beaches so that we're able to do a better job of preventing that pollution in the first place.”

The data is used to influence policy and create better regulation over the use of certain materials in marine environments, such as Styrofoam, said Hoyland.

Styrofoam is a highly toxic substance widely used in the marine aquaculture industry. It breaks down into tiny pieces that are almost impossible to remove from the environment, described Hoyland.

A 2020 report from the province titled What We Heard on Marine Debris in B.C said many participants suggested Styrofoam makes up a “large proportion of marine debris.”

“Industry is moving towards alternatives to unprotected polystyrene docks; however, legacy issues of exposed StyrofoamTM remain even as new ones are being installed,” read the report. “The aquaculture industry alone has over 400 floats made from exposed StyrofoamTM that would need to be replaced and recycled in the coming years.”

Currently, the project is in the debris processing phase where various types of material are prepared for recycling and data collection, said Hoyland.

“The better informed we are on the problem we're facing, the better equipped we are to implement measures to prevent plastic pollution at the source,” she said.

Surfrider Pacific Rim has been doing remote beach clean-ups on the west coast of Vancouver Island for the past five years, said Hoyland.

“The sad thing about beach cleaning is that it just treats the symptoms, it doesn't stop the pollution,” she said. “Every year we go back, and every year there's more stuff.”

Hoyland said she hopes additional funding is secured for next year to “keep up with the flow of plastic that’s coming in.”

Packwood shared a similar sentiment and said, “it can't just be a one-time thing.”

“It has to be ongoing,” she said. “Once the north winds come through, it pushes all of the debris into the backside of the islands.”

Freezers, fridges, and legacy debris from the Japanese tsunami were some of the items Packwood said she found during her time on the islands.

“It was super eye opening,” she said. “It's really affecting our ocean and all of its inhabitants.”

As Packwood reflected on her time on the Broken Group Islands, she described it as “emotional.”

“I'm super passionate about my own territorial lands,” she said. “My grandfather grew up on Benson [Island] and I spent a lot of my time in my youth on Nettle [Island] in the summers. So, this just really hit home for me.”

For Packwood, the experience brought her closer to her ancestors.

“I felt gratitude for being out there and being able to do this for my people,” she said. “I want to be a protector of the land.”