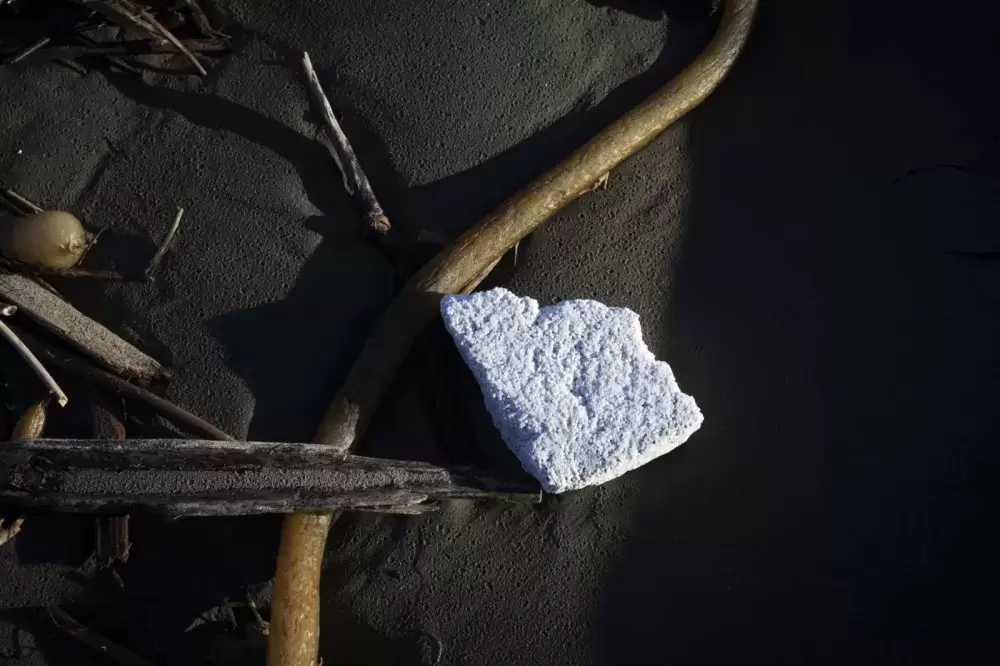

Around two weeks ago, Nicole Gervais said chunks of Styrofoam started washing ashore on the northern end of Long Beach, near the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation community of Esowista on Vancouver Island.

That section of beach, entitled T̓ayus, has been closed to non-residents since 2020 to keep community members safe from COVID-19.

Free from the disturbances of visitors and dogs, Gervais said large flocks of birds have returned to the beach to feed on bloodworms and sand fleas.

But as the Styrofoam breaks down into smaller pellets after each high tide, Gervais said she’s increasingly worried about the Sandpipers and Oystercatchers.

“They eat the broken bits of Styrofoam and it kills them,” she said.

Gervais has been living on the edge of Long Beach since 1987 and said that she’s used to seeing plastic water bottles wash ashore, but she’s never seen this amount of Styrofoam.

Unlike the Styrofoam used for docking floats, Gervais’ daughter, Gisele Martin, said the pieces that now litter the high-tide line all the way to Schooner Cove have edges carved into them.

It’s packing material, she suggested.

Parks Canada said it’s aware of the Styrofoam and other materials coming ashore, which are typical at this time of year due to higher tides.

But some coastal peoples, like Gervais, are concerned that the Styrofoam is a consequence of the Zim Kingston container spill from Oct. 22.

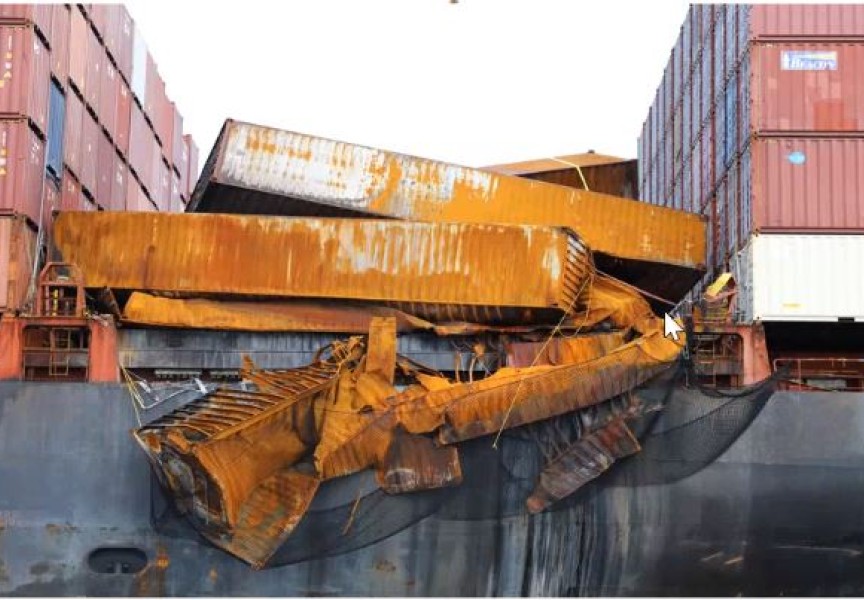

Only four of the 109 shipping containers that were knocked from the cargo ship off the coast of Vancouver Island have been located.

The Canadian Coast Guard believes the rest have sunk.

During a media briefing after the spill, Canadian Coast Guard Deputy Federal Incident Commander Mariah McCooey said the watertight integrity of the overboard containers is “not that great.”

It’s only a matter of time before the 105 missing 40-foot shipping containers rupture, said Alys Hoyland, Surfrider Pacific Rim beach clean coordinator.

“The stuff that's inside of those containers will start washing up on beaches,” she said.

But without any way of tracking the Styrofoam, there’s no way of knowing where it came from.

It’s “difficult” to identify the source of Styrofoam or packing materials, the coast guard said, adding that packing materials were not included in the ship’s manifest.

The manifest, which identifies the contents of the overboard containers, has not been made public, and none of the local clean-up organizations, such as Epic Exeo, Ocean Legacy, Rugged Coast or Surfrider, have received a copy.

Hoyland said that without knowing what’s inside the shipping containers, it’ll be “incredibly hard to prove the extent of the spread,” or to hold the ship’s owner accountable.

Clean-up efforts have been ongoing on the north coast of Vancouver Island, where the four of the shipping containers were found.

“To date, approximately 27,360 kilograms of debris has been removed from northern Vancouver Island beaches by the contractor, First Nations, and volunteers,” the coast guard said.

Jurassic Point is in the final stages of being cleared and the beaches where debris was reported are now “considered to be clean,” the coast guard added.

“The ship’s owner will continue to check the known accumulation sites for debris every few months and remove any debris likely to be from the MV Zim Kingston,” the coast guard said.

Ashley Tapp is the co-founder of Epic Exeo, a non-profit organization based out of Port McNeill that focuses on clean-ups along the north coast, where the containers were found.

“We’re a little upset that they think they’re done,” she said.

On Dec. 14, Tapp returned to Cape Palmerston and Grant Bay, where clean-ups were held. Pink plastic unicorns, plastic green dinosaurs, cologne bottles, baby oil, grey rubber mats, Styrofoam and packing materials remained on the beaches, she said.

“You can't just go and clean a beach and then wipe your hands of it,” Tapp said. “[Debris] keeps coming back.”

Grey rubber mats linked to the cargo spill have also started washing up in Florencia Bay and in the Hesquiaht Harbour, said Hoyland.

One week ago, Ray Williams reported that large chunks of Styrofoam started washing onto the beaches around Yuquot.

Similar reports are being made from Haida Gwaii, said Hoyland.

It’s “troubling” that this isn’t being considered an environmental disaster, she said.

“This is not just a case of some missing goods,” said Hoyland. “This is an environmental catastrophe that’s playing out on our shorelines right now.”

The coast guard said it continues to work with the ship’s owner and that they’re taking “all measures considered proportionate to the hazard posed by the overboard containers.”

“The owner is working on a plan to conduct a sonar scan of the area where the containers went overboard, around Cape Flattery, and an assessment of risk that the overboard containers could pose to the environment,” the coast guard said.

As shipping supply demands increase, Courtenay-Alberni MP Gord Johns said there are more cargo ships traveling through the Strait of Juan de Fuca than ever before. And with the frequency of extreme weather events rising, “we know more incidents are going to happen,” he said.

The federal government needs to create a tactical response plan so that companies are held accountable, said Johns.

Currently, the delegation of authority falls in the lap of the shipping company, who often doesn’t have local ties to the area, he said.

Indeed, contractors hired by the owner of Zim Kingston to organize beach clean-ups on the north coast were not local and were unfamiliar with the geography of the area, said Hoyland.

“It was more than a week before any kind of clean-up effort started,” she said. “And the longer it took for the clean-up to start, the worse it got.”

Contents from the four containers “were spreading further and further with every tide,” Hoyland said.

Despite having extensive knowledge of the area, Tapp said it took at least a week before she was asked to coordinate clean-ups south of Palmerston Beach and Raft Cove. While accommodation, food and fuel were covered, wages were not.

Moving forward, Hoyland said emergency response plans need to be developed in consultation with the First Nations whose territories are being impacted, as well as with the “environmental non-profits that have been leading clean-up efforts like this for decades on these coasts.”

“We're living in a changing climate,” she said. “We really need to start looking at these big picture changes that we can make in order to keep the environment and the ocean safe for future generations.”

The coast guard said that Quatsino, Ehattesaht, Kwakiutl and Tlatasikwala First Nations were all brought on by the ship’s owner to assist with beach clean-up efforts and to identify resources at risk in the impacted areas.

Back on Long Beach, Gervais said she picks up what she can, but the amount of Styrofoam that’s tangled in kelp and driftwood is too big of a job for one person.

As the Styrofoam breaks apart and becomes more difficult to remove from the ecosystem, Martin questions its impact on the intertidal food and medicine her nation relies on.

People travel from all over the world to look at the scenery outside Gervais’ living room window.

It’s beautiful, she admits, but it’s also a responsibility.

“The ocean is alive,” she said. “It’s got a life of its own and we need to respect it. It’s a responsibility to notice what’s happening and raise the alarm.”

The public is asked to report any sightings of marine debris they believe is from the MV Zim Kingston to the coast guard by calling 1-800-889-8852