Nearly a year after the Zim Kingston lost over 100 shipping containers at sea west of Vancouver Island, a House of Commons committee has concluded that Canada is ill-prepared to deal with marine cargo accidents.

“[C]oastal communities are bearing the brunt of cleanup efforts,” stated the House of Commons Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans in a report released this month. Based on an analysis of the Zim Kingston incident - including hearing from 21 witnesses in government agencies, coastal response organizations and First Nations - the committee’s report lists 29 recommendations, stressing what’s needed to overcome shortcomings that led to 105 containers being lost in the Pacific.

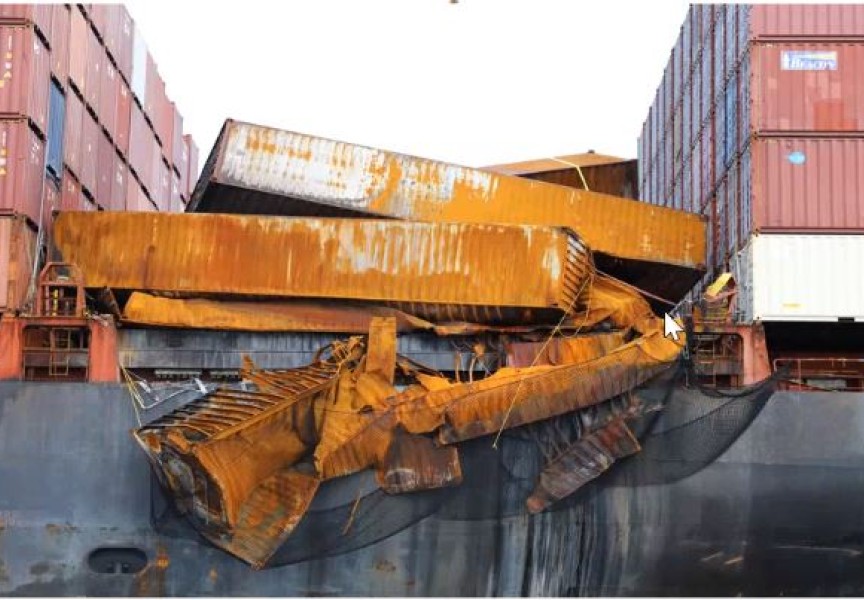

On Oct. 21, 2021 the Zim Kingston reported losing 40-foot shipping containers in stormy weather before the vessel entered the Juan de Fuca Strait, 38 nautical miles south of Ucluelet. Owned by the Danaos Shipping Company from Greece, the Zim Kingston originally reported missing 40 containers, but this tally ended up being 109. The ship continued eastward, and a fire emerged when the vessel was south of Victoria.

Coast Guard shortcomings

The Canadian Coast Guard responded, but the government agency’s effectiveness led the parliamentary committee to determine that Canada has “deficient” resources in marine firefighting and the towing of vessels. The fire was first reported at 12:45 p.m. on Oct. 21, but the Coast Guard wasn’t on the scene until 5:30 to 6 p.m. that afternoon, states the committee’s report. The Coast Guard’s emergency towing boat arrived on the scene at 6:30 the following morning, nearly 18 hours after the fire was first reported.

“[T]he situation was saved by the fortuitous presence of two offshore supply vessels with firefighting capability in the vicinity,” stated the report.

Canadian Coast Guard Deputy Commissioner Chris Henderson told the committee that the federal agency “was well-positioned to respond quickly and effectively to this incident.” But further correspondence from the Coast Guard revealed that the initial model of where the containers were believed to be drifting came from the US Coast Guard, which informed early decisions on how to respond to the offshore incident.

In light of these findings, the standing committee recommends that DFO consult with the Coast Guard on how to improve its marine firefighting capabilities, as well as look into standards that would require tracking devices in shipping containers. This would be part of a “marine debris monitoring and management plan” that the DFO is tasked to implement, addressing all forms of synthetic material that ends up in the ocean, with research to better understand the impacts of polystyrene on marine environments. The committee also recommends a push to ban polystyrene in international marine transport.

Just four of the 109 containers that went missing were recovered, leaving those who live on the west coast of Vancouver Island to suspect that the unusual matter washing up on their shores in late 2021 came from the Zim Kingston. Esowista resident Nicole Gervais found unusual debris like grey rubber mats and toys on the beach, while Ray Williams of Yuquot encountered unusually large chunks of Styrofoam on the Nootka Island shore in December.

“It’s unusual to see that kind of stuff come ashore,” said Williams in a past interview with Ha-Shilth-Sa. “I have a strong suspicion.”

The presence of such matter far north of the Zim Kingston accident is cause for concern, according to Stafford Reid, an environmental emergency planner and analyst who provided input to the standing committee. He stated that polystyrene foam and small plastic pieces of marine debris are “much more insidious and have much more long-term impact than even oil.”

First Nations are ‘best positioned’ to respond

Under Canadian law, a shipping company is required to take care of cleaning up debris after a marine accident. Danaos hired the Resolve Marine Group, a US-based company with an international reputation. But this was not necessarily the best contractor to lead the recovery effort, said Karen Wristen, executive director of the Living Oceans Society, in her statement for the committee.

“In that void, the ship's owner retained an agent with no shoreline salvage experience, no knowledge of the local terrain, infrastructure or response assets, and gave him command of the entire operation,” she said. “That agent decided to prioritize the removal of goods that were still contained in a beached container over the goods that were strewn all over the beach. That choice is largely responsible for the fact that debris is now strewn on every beach from Haida Gwaii to Tofino, at the very least.”

Although the committee determined that the Coast Guard and the province kept coastal communities well informed of how the effort was progressing, communication among those who responded to the lost containers was poorly coordinated, leaving coastal residents to shoulder more than their fair share of cleanup. The committee addressed this issue by recommending the formation of a spill-response task force composed of government agencies, First Nations and non-government organizations.

Terry Dorward, project coordinator of the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation’s Tribal Parks, stressed that more resources for the First Nation would have improved how the offshore incident was handled.

“We require direct funding to build response capacity for coastal First Nations, and to provide emergency training and response materials to First Nation communities who are best positioned to be the first responders in the event of a spill,” Dorward told the parliamentary committee. “We know we can safely and effectively mobilize to reduce response times and mitigate the challenges of bringing in distant federal response agencies like Transport Canada, the Coast Guard and external contractors.”

Container contents remain a mystery

Two of the lost containers contained hazardous materials: 23,800 kilograms of potassium amylxanthate, a yellow powder used in mining to separate ores, and 18,00 kilograms of thiourea dioxide, a white bleaching compound used in the clothing industry to remove colour from natural fibres. In an update provided in March the Coast Guard reported that, based on consultations with Environment Canada, these chemicals should not have long-term impacts on the marine environment.

But where these two containers are remains a mystery, and the exact contents of the other missing sea cans will continue to leave those who closely watch the shorelines to wonder if they haven’t seen the last of debris from the Zim Kingston. The ship’s cargo manifest was not publicly shared after the accident, as privacy laws limited this information to those who shipped and ordered the goods.

“When we can't accurately track where these containers are and we don't know where the load of chemicals will eventually spill, it's almost impossible for us to engage in any long-term monitoring and to fully understand, from a scientific perspective, what the ramifications of that chemical being in the aquatic environment will be,” said Alys Hoyland, a youth coordinator for Surfrider Foundation Canada, to the standing committee.

“We really have no idea what to expect from the missing sunken containers. Two of them are known to contain a chemical that is acutely toxic to aquatic organisms, and we have no idea where they are or what condition the cargo is in, and 102 of the containers are simply mysteries,” stated Wristen. “How, then, are we to begin to hold the polluter to account for the risk or to plan and pay for a response when those sunken containers break up and release their content?”