A harm reduction outreach program is working to keep people alive in the midst of a spiraling illicit drug epidemic that has devastated man Nuu-chah-nulth families.

At the NTC Disability Access Awareness Committee Health Ability Fair, held Oct. 25-26 at the Alberni Athletic Hall, Gina Amos, a harm reduction outreach worker with the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, told the crowd that in the first seven months of 2023, 1,455 people lost their lives to illicit drugs in British Columbia. In the month of July alone, 198 British Columbians died due to drug use.

“We’re all affected – we’ve all lost family or a friend,” said Amos.

“What is harm reduction outreach, she asked.

“It starts with kindness, compassion and respect for people,” said Amos. “It is support offered with heart.”

Illicit drug use is an addiction, a condition considered to be a disease by most medical associations.

“In harm reduction, there may be a window of opportunity that we don’t want to miss,” said Amos. “In that moment, they may want to reach out for help to quit drugs. We want to be there to offer help, to be with them, to offer what we have.”

She said that the workers approach people without judgement or an agenda. She uses a gentle approach, she says, because many of the people in the street suffer from illnesses or wounds, and they may be afraid to seek medical treatment.

“They are looked down on, so they are treated badly,” said Amos.

Some have had bad experiences in medical facilities. Sometimes, they just want someone to sit in silence with them, she added.

Outreach workers help with whatever they have. It could be food, clothing, or toiletries, but they also help with clean drug supplies, which can be perceived by some people as supporting addictions.

“People ask why we give away things like pipes,” said Amos. “We do it to help stop the spread of disease.”

This not only expands opportunities for people to beat addiction, but also puts less of a strain on the healthcare system.

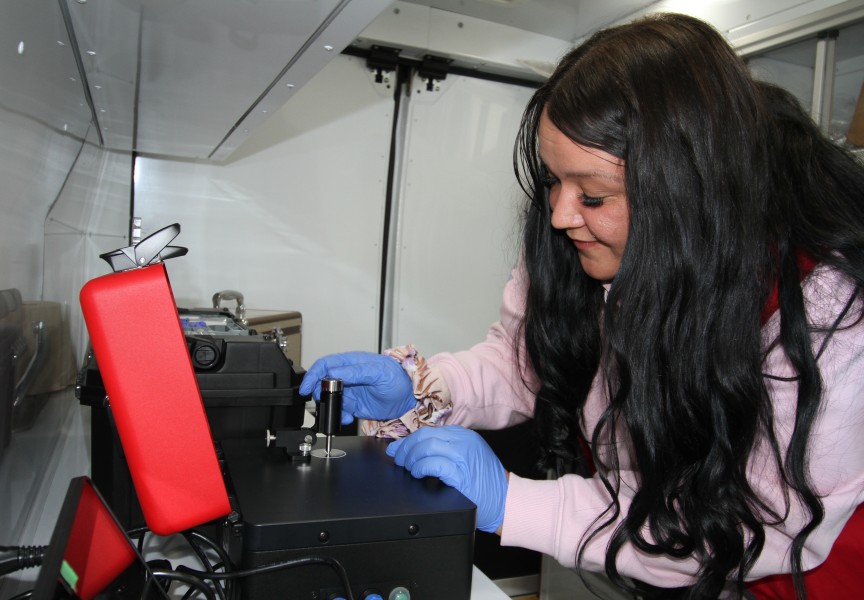

In her work, Amos also offers Naloxone training, the life-saving antidote for opioid overdose.

“It saves lives and anyone with a status card can go to a pharmacy and get a Naloxone kit for free,” said Amos, adding that a nasal Naloxone kit is worth $298.

When an addict survives an overdose they go straight into withdrawal symptoms, according to Amos. They will experience pain, agitation, nausea.

“They say it’s like the flu, only 10 times worse,” she added.

Amos pointed out that addictions were never a part of Nuu-chah-nulth culture, so there are no solid cultural methods to address the situation. Amos reminded people that we are all family.

“We are a loving and giving people so, it makes sense to treat our people with love and respect while we do our best to figure things out,” she said.

Lisa Watts, a Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls family support worker, followed up with a presentation on grief and loss.

“Grief is messy. There is no right or wrong way to deal with your pain,” she told the crowd.

“We all love someone deeply and we want everything good for them,” said Watts.

But when they get into addictions and all the bad behavior that comes with it, that leaves people conflicted.

“Then, when we lose them, the dream ends,” said Watts.

She recalls the ‘60s and ‘70s when alcohol addiction was killing Indigenous people. She said it was about 30 years ago when she first started seeing death from drugs.

“Now we’re dealing with a tidal wave,” said Watts.

Drug abuse, she said, is both a disease and a poison, so it comes with stigma and judgment. And the loss of a loved one to drugs is sudden and traumatic.

“We have one constant,” said Watts. “We are human, and we love deeply.”

Everyone has been touched by the loss of someone, or is living with the knowledge that their loved ones are addicted. Watts asked people to put those people in their thoughts with love.

“Remember, there are some warriors that walked through it and came back to us. It can be done,” she said.

Watts had this to say to anyone suffering from grief and loss: You’re not alone and remember to be kind to yourself. Be ultra patient with yourself, she told the crowd.

For those struggling with grief, Watts introduced an internet resource called Bounce Back. Offered by the Canadian Mental Health Association, Bounce Back is a program that allows people to work through their grief in modules. They can do the program in their own time and at their own pace.