Has the decriminalization of drugs gone too far in British Columbia? Or are we just in an early stage of a paradigm shift in how addiction is treated that will eventually result in fewer overdose deaths?

B.C. became Canada’s first province to decriminalize illicit drugs last year, with an exemption from Health Canada under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. Coming into effect Jan. 31, 2023 for three years, the exemption makes it legal to have or consume up to 2.5 grams of street drugs like cocaine, methamphetamine and heroin. This was attempt to curb the continued tally of fatalities from B.C.’s opioid crisis, which had reached an average of nearly seven deaths a day, making drug-related fatality the leading cause of unnatural deaths in B.C. – surpassing homicide, suicide and car crashes combined. Fentanyl has been detected in 85 per cent of drug-related fatalities, according to toxicology data from the B.C. Coroners Service.

“The decriminalization of people who are in possession of drugs for personal use is one additional step to save lives as we continue to tackle the toxic drug crisis in B.C.,” stated Provincial Health Officer Bonnie Henry when the exemption was granted last year. “This exemption will help reduce the stigma around substance use that leads people to use alone and will help connect people to the health and social supports they need.”

Since decriminalization was introduced early last year, drug use was always prohibited near schools, playgrounds and skate parks. But the prevalence of illicit drugs in public, including in hospitals, has since led the province to scale back its approach to the issue. On May 7 the provincial government got approval from Health Canada to amend the decriminalization policy and make it illegal to consume illicit drugs in public, which includes in parks, on transit and in hospitals. People can still legally use in a tent, a home or at a supervised consumption site.

“While we are caring and compassionate for those struggling with addiction, we do not accept street disorder that makes communities feel unsafe,” stated Premier David Eby in a recent press release.

The province announced that police now have the ability to “compel” narcotic users to leave a public area, “seize the drugs when necessary or arrest the person, if required.”

“We’re taking action to make sure police have the tools they need to ensure safe and comfortable communities for everyone as we expand treatment options so people can stay alive and get better,” said Eby.

‘Reckless decriminalization experiment’

This fall a provincial election is on the horizon, and calls from the opposition BC United party are getting louder for the government to reign in a policy that some feel has quickly gotten out of control.

On April 4 in the B.C. legislature MLA Shirley Bond, who represents Prince George-Valemont for BC United, called the province’s approach to drug use a “reckless decriminalization experiment”.

“The NDP have created a free for all with open drug use – shockingly, even within our public hospitals,” said Bond.

She pointed to a leaked memo from a Northern Health supervisor last summer, which instructs staff that they are to permit the open use and exchange of illicit drugs in hospitals, besides smoking.

“Patients can use substances while in hospital in their rooms – they can either be provided with a Narcan kit or have one available,” stated the memo, referencing a method of treating overdose. “If a patient has overdosed on substances we use Narcan and provide teaching.”

The memo also said visitors bringing in illicit drugs are not to be restricted.

“Only restrict if they are violent, intoxicated or posing a problem,” it stated. “We don’t restrict if they’re dropping off substances or suspect of the same.”

“The entire memo is outrageous,” said Bond while in the legislature. “Under this NDP government, illicit drug use, and yes, even drug trafficking in hospitals are not just tolerated, but they are endorsed.”

The issue is also being debated in Ottawa, where the Conservatives are calling for the federal government to reject requests from the cities of Toronto and Montreal to decriminalize the personal possession of illicit drugs, and deny any future such applications from municipalities and provinces.

Courtenay-Alberni MP Gord Johns believes that the federal government hasn’t given the issue the attention it needs, due to negative attitudes still directed towards those who use substances.

“Criminalizing people causes more harm,” said the NDP member of parliament. “We need to scale up safer supply of substances.”

Johns is frustrated that Ottawa has yet to declare the opioid crisis a national public health emergency.

“We need a coordinated, integrated and a compassionate response to the toxic drug crisis. We do not have that yet,” said Johns. “We need the federal government to come in with really significant investments to meet the province where they’re at.”

Progress evident since decriminalization

Since the opioid crisis was declared a public health emergency in British Columbia over seven years ago, policy has been directed to treat illicit drug use as a legitimate health condition, not an ethical shortcoming.

As a registered nurse, this is the approach Sarah Lovegrove takes to illicit drug users. She works in Nanaimo and is a nursing professor at Vancouver Island University’s Health Sciences and Human Services department.

“It’s a terrible mistake for the government to turn around efforts for decriminalization,” said Lovegrove. “It will only result in increased deaths, increased injury, and increased impacts on communities and families of people that use drugs.”

The most recent statistics could be seen as progress for those on the front lines of the opioid crisis. Recently the B.C. Coroners Service reported 192 drug-related deaths in March, an 11-per-cent decrease from the same month last year. Part of the solution, some would argue, is bringing drug users out of the shadows, as 84 per cent of deaths so far tallied by the Coroners Service this year occurred inside.

Lovegrove has seen decriminalization allow more illicit drug users to access health care.

“I would often hear from people who use drugs in Nanaimo that they would rather die on the street than go to the emergency department,” said Lovegrove. “At least decriminalization allows the legal space for people to enter into these services without fear of being put in jail.”

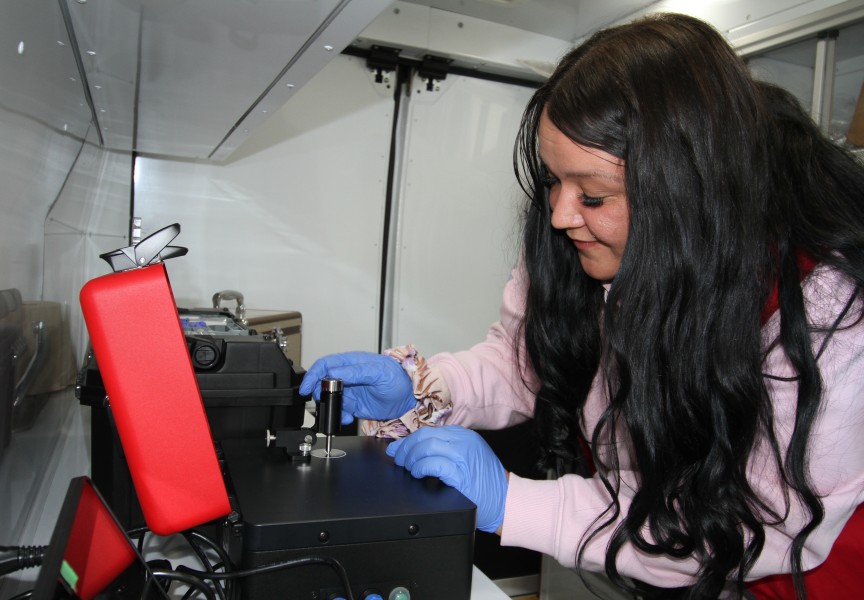

Indigenous people have faced a fatality rate five times that of the rest of B.C.’s population, according to data reported from the First Nations Health Authority. On Vancouver Island the opioid crisis has been prioritized by the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council’s Teechuktl department, which introduced a harm reduction van in March. The vehicle supports drug users in Port Alberni, Nanaimo, Campbell River and Tofino, providing essentials like food, clothing, water, as well as clean syringes and pipes to prevent the spread of infection while substances are being consumed. Staff in the van even treat wounds, as illicit drug users have been reluctant to access health care in the past.

“Criminalizing drug use isolates drug users more from what they need most: connection to others, and support to access harm reduction services and treatment programs,” said Teechuktl Manager Sanne van Vlerken.

Van Vlerken believes that a shift in public perspective is necessary to better treat those using illicit drugs, as there remains more shame attached to the activity than consuming alcohol or smoking. She fears that the province’s latest changes to decriminalization could create further harm.

“This would have the potential to reverse the progress made in shifting towards a more compassionate and health-focussed approach,” said van Vlerken. “We need to provide more information and awareness about drug use so it becomes more socially acceptable and less stigmatizing and judgmental.”

There are 50 supervised consumption sites in B.C., with only one fatal overdose reported at these facilities since the first of them were established over a decade ago. Lovegrove believes that hospitals need to have these sites as well to give drug users more safe spaces.

“In my opinion, there should be as many overdose prevention sites in our communities as there are bars and liquor stores,” she said. “I see drug use and substance use as morally neutral, neither good nor bad - it just is a valid response to ongoing colonization, experiences of trauma, adverse childhood experiences. That’s how I understand and explain the instances of substance use within our communities.”

An individual’s strength from within

Few people have a more intimate knowledge of drug use than Rita Watts. She used crack-cocaine for 22 years, and, over a decade into sobriety, supports family members who are currently struggling with substance addiction. In recent years Watts has worked with Port Alberni’s Community Action Team to produce the video Human First – Hear Their Voices, where she interviewed 50 illicit drug users in the community. A survey from the project found that 80 per cent of participants felt judged or stereotyped in the community, while only 31 per cent said their voices were heard and acknowledged, and 56 per cent felt they could speak freely about needs while seeking healthcare.

“There’s a lot of people out there that could sure use a helping hand and to realise that they are loved,” said Watts of illicit drug users. “Their spirits aren’t destroyed, but they’re destroying it.”

While she supports drug users to have their story heard, Watts does not believe that public use should be socially acceptable. The extent of the issue hit her last year while she was at the Nanaimo Regional General Hospital after her son’s drug overdose.

“The hardest thing about being in that hospital was that there were people in addictions that were in and out of there all the time,” said Watts, who recalled feeling the effects of drug inhalation just from walking through the parking lot. “They would be smoking, they would be doing their drugs right in the hospital, right in the parking lot. You walk right through it. I go the security guard, he said, ‘I’m very sorry, there’s nothing I can do about it’.”

The prevalence of drug use in Port Alberni has also made it harder for Watts’ daughter to recover from her addiction to substances, she said.

“Having people being able to do their drugs whenever they’re free to is so, so wrong,” said Watts, whose daughter is trying to gain a handle on her addiction. “My daughter has that, but where can they go? They can’t go anywhere. They’re stuck here in Port Alberni.”

Last year the Alberni-Clayoquot health region recorded drug-related fatalities at a rate of more than double the provincial average. It’s a crisis that prompted the Tseshaht First Nation along with Port Alberni’s Community Action Team and the Kuu-us Crisis Line Society to release a four-pillar strategy early this year, which prioritized the need for a fully funded “inclusive, innovative, timely and barrier free” detox and recovery facility in the city.

Meanwhile the province has added 607 publicly funded substance-use beds since 2017, including 179 new spots added to Vancouver Island and 16 brought to Port Alberni. This brings to total substance use beds in B.C. to 3,633, with 686 in the Island Health region.

“It’s important to note that bed-based treatment only represents a small part of a much broader continuum of care when it comes to treatment options for people living with addictions,” wrote the Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions in an email to Ha-Shilth-Sa. “Beds are typically most appropriate for people who require a higher intensity of services and supports to address complex or acute mental health or addiction problems.”

As politicians debate public policy and health practitioners struggle to help those who use an increasingly toxic supply of street drugs, Watts reflects on what led her to overcome substance use.

“You can’t change somebody that does not want to change. They have to want to change,” she said. “It took me 22 years to realise that, know what, you’re either going to die doing this or you’re going to live to watch your grandchildren grow up.”