Shae Doiron grew up around sports in Port Alberni, and has organized several ball hockey tournaments, but what unfolded over the last weekend of January in a packed Maht Mahs gymnasium was something different.

As part of its long tradition of hosting the sport on the Tseshaht reserve, Maht Mahs took in 14 teams for three days of hustle and sweat before a lively crowd – all in honour of those lost due to drug use, a phenomenon that has become disturbingly widespread amongst First Nation communities.

“It was a very emotional weekend for a lot of people,” said Doiron. “Friday to Sunday it was jam packed. I’ve hosted multiple tournaments, but that was the biggest one by far.”

Doiron played on a team honouring her brother Charles, who died from an overdoes on Jan. 28, 2022. Three years since losing her only sibling, this marked the first time Shae publicly recognized her beloved brother. Her team also played for Benjamin Fred, who passed from overdose last July.

“The tournament allowed us to represent people we lost, and to try and help families have a good time,” said Doiron. “It was a whole community effort.”

Teams from Port Alberni, Duncan, Port Hardy, Alert Bay, Duncan, Victoria and even as far as Williams Lake competed in the tournament, making up 11 men’s teams and three women’s.

“I knew there was going to be a huge response because of how much fentanyl has affected not just our community or my family but so many others all over,” added Doiron. “I had immediately 16 men’s teams wanting to be in.”

‘The Realm of Hungry Ghosts’

The widespread interest in the tournament isn’t surprising considering the extent that illicit drug use has impacted families across the province. Since the provincial government declared a public health emergency in April 2016, death by overdose has claimed over 16,000 lives in B.C. – and more than 50,000 across Canada. In B.C. this means that illicit drug use has become by far the leading cause of death for people under 60 - more than homicide, suicide and car accidents combined.

The fatal tally began to rise a decade ago when fentanyl claimed a prevalent place in the illicit drug supply. More impactful than morphine, Fentanyl is an opioid that was originally designed for and aggressively marketed in the medical community as a painkiller. A lawsuit is underway from the province against drug producing and distribution companies alleging that the painkiller was pushed on the public without a responsible regard for the societal effects.

The toll of illicit drug use on Indigenous communities has been particularly devastating, as they have been impacted with a fatality rate six times that of the rest of B.C., according to the First Nations Health Authority. In September the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council took a stand on the issue with the declaration of a state of emergency due to the overdose crisis and its associated mental health issues that have hit so many families. Since then the NTC hired a consultant to determine the specific needs of its 14 nations, while collecting precise numbers on the losses in each community.

“We know fentanyl. It’s changed our life forever,” said Doiron, who has also battled addiction in her life.

This month she marks two years of sobriety, although Doiron is keenly aware of the dangers of falling into addiction again.

“I had 12 years of sobriety at one point, I kind of went through a rough patch and found myself back in active addiction,” she said. “If you can have a 6-pack on a Friday night, and make it to work on Monday, then all the power to you. I’m not that kind of a person.”

For years Dr. Gabor Maté worked in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, a neighbourhood that continues to see the highest rate of drug-related fatality in B.C. In his book The Realm of Hungry Ghosts Maté puts forth the view that addiction is the result of a deep-rooted need for relief from a stress that was established in one’s early years. Whether its excessively shopping or shooting heroin, Maté finds that addictive behaviour comes from a struggle for escape from pain that has tormented a person since childhood.

“I’ve experienced a lot of trauma as a child growing up,” said Doiron. “It’s not that I lived in an unsafe home, however the topic of intergenerational trauma is brought into our lives in unfortunate ways.”

The roots of violence go back multiple generations, explains Doiron, whose Tseshaht First Nation had the Alberni Indian Residential School operating on its main reserve for most of a century. She has found that the route to addiction is a lack of connection to oneself and the community.

“It’s unfortunate that stigma is still very active in communities and on an individual basis,” said Doiron. “When I lost my brother, I now suffer from PTSD of trying to save his life. That has just enhanced everything that I thought I overcame, however I’m still experiencing the ripple effects of being hurt myself.”

‘A cycle of addiction’

The last time Shae spoke to her brother on Jan. 28, 2022 was when she asked him if he wanted a cup of coffee. Charles was resting in his parent’s trailer, but after Shae had gone to an appointment that afternoon it became clear something was very wrong when she got multiple phone messages from family unable to reach him.

“4:55 p.m., Friday, Jan. 28, 2022 I called my dad and said, ‘Go check on Chaz, I’m pretty sure he’s using’,” recalled Doiron. “When I got there my father was doing chest compressions on my brother. He was in such a state of shock.”

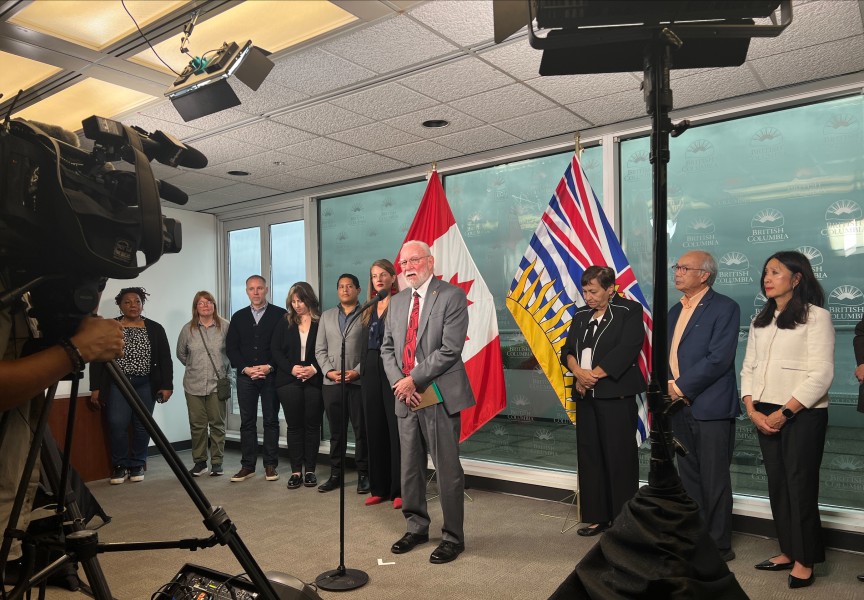

During a press conference in January, B.C. Minister of Health Josie Osborne addressed the isolation people struggle with while in the grip of addiction.

“Many people are trapped in a cycle of addiction and they feel that there is no way out,” said Osborne, who is also the NDP MLA for Mid Island-Pacific Rim. “For those who need help, it’s often even harder because of the barriers that stand in the way of them getting the treatment that they need.”

Osborne offered these words before announcing 26 new substance-treatment beds that the province has added since last August, including six more in Nanaimo, part of the over 3,700 publicly funded spaces now available across B.C. But despite the NTC’s state of emergency, none of the additional beds have been set up in western Vancouver Island.

Doiron said her brother had been clean for 30 days before the overdose that claimed his life. Charles had been trying to get into treatment.

“Learning how to cope in this world today, when it’s easier to get drugs and alcohol than it is to find help, that’s the biggest struggle,” she said. “When my brother passed, he was trying to find places to go. Unfortunately, there wasn’t a lot of options for men. He had a bad day and decided to use and lost his life as a result of it.”

Doiron reflects on the challenges of finding where to take a loved one for treatment, as facilities have long wait lists and some have restrictions, like prohibiting those who have criminal charges.

“It’s not just about the first 10 days of drying out,” she explained. “After the 10 days, these people are still broken and they don’t have drugs and alcohol as a coping mechanism anymore. So how can we help them?”

Recovering in memory of Charles

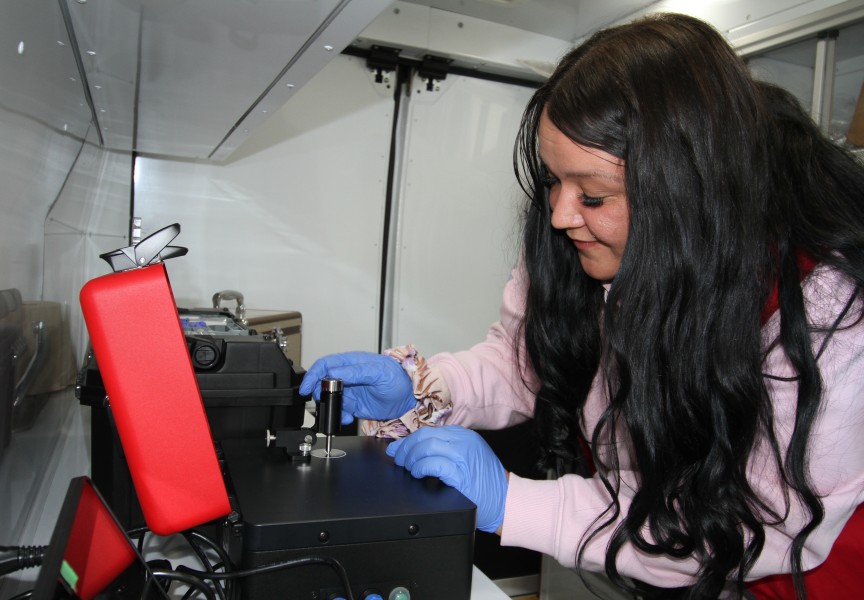

After cash awards for the winning teams and other costs, the ball hockey tournament was able to garner almost $6,000. Doiron is using this to give contributions to organizations helping those affected by the drug crisis, including the Kackaamin Family Development Centre. The fundraising has also helped with other initiatives, like providing food to those who use Port Alberni’s Overdose Prevention Site.

“Sports is the second-best connection, aside from cultural, to where we can stay connected and just be together,” said Doiron. “Potlatch is huge. There’s really not that many anymore where we can stay connected, where we can still have that balance in a society that really isn’t designed to be native.”

Doiron now looks back on her 12-year-stint of sobriety, drawing on the lessons she gained and those who supported her, including “a pretty powerful family that is in recovery as well.”

“It was really hard to get out of it, but I managed to get out of it again,” she reflected. “I’m choosing to live a recovery life in memory of my brother.”