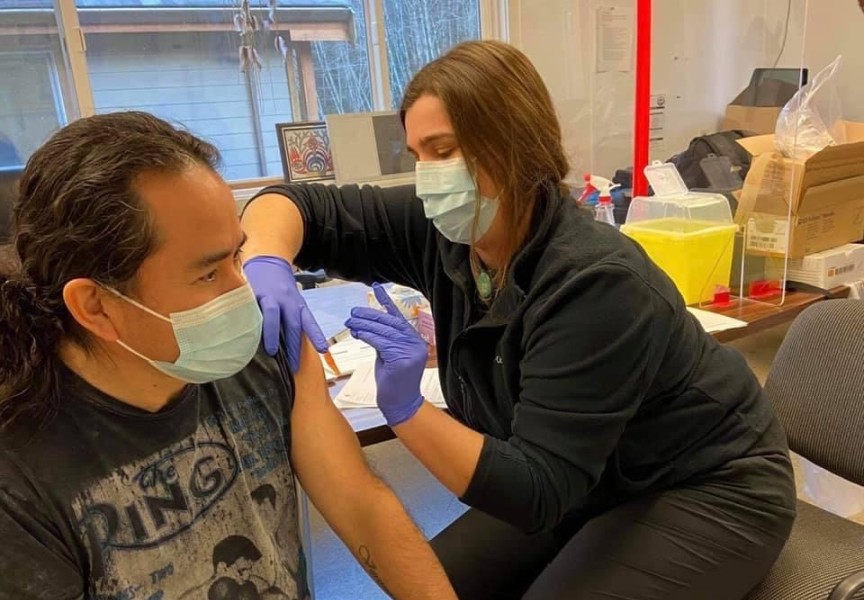

The Ehattesaht/Chinekint are asking the Ministry of Health to put the First Nation “high on the vaccine list”, as one quarter of its on-reserve community in Ehatis has now been infected with COVID-19.

“We all know how challenging COVID is and for those of us who have not been infected and for our vulnerable members, we need this kind of attention,” states a recent notice from Ehattesaht chief and council.

One day before the first round of vaccines arrived in British Columbia, Ehattesaht reported that the case count for the small village next to Zeballos had reached 25 on Dec. 13, including six active infections which were being isolated. The previous update from the First Nation’s chief and council noted that active cases were being moved to locations in Campbell River to be separate from the Ehatis community, which has been under a lockdown order for weeks.

On Dec. 14 the B.C. Ministry of Health announced that the initial 4,000 doses from Pfizer will be given to long-term care and front-line health care workers in the Lower Mainland. B.C. plans to immunise 400,000 people by March, but for the time being it appears Ehatis residents will be forced to wait for the respiratory disease’s spread to subside.

“With each day that passes we are getting closer to having COVID out of our community,” reads a recent notice from chief and council. “We need everyone to be more careful than ever.”

Since late November residents have been advised to isolate and only socialize with those in their household, but as infections spread through Ehatis, on Dec. 6 the First Nation tightened its restrictions even further. The Infectious Disease Bylaw was enacted, bringing tickets and the withdrawal of member supports to those who have visitors in their home or leave the community without permission from the First Nation’s government. School bus service and patient travel is suspended, while gatekeepers in Ehatis deny entry or exit without prior approval from the First Nation.

“When you go for a walk stay six feet apart from everyone and wear a mask,” reads a Dec. 6 notice from the First Nation. “Please do not leave the reserve and go into town.”

With Christmas less than two weeks away, arrangements were made for packages to be left at a trailer in Campbell River’s Super Store parking lot on Dec. 17 for gifts to make it into the reserve community.

Despite the 25 infections, Ehatis has yet to report any hospitalisations. COVID-19 overwhelmingly afflicts the elderly, and the First Nation’s good fortune could be due to the age of those infected within Ehatis. The majority of cases have involved residents under 40 years, with just one infection over 70 and another in the 60-69 age range.

The first two cases were reported Nov. 21, one day after the community was alerted to a possible exposure at the nearby Zeballos school. Someone who visited the school, Ehatis and the Nuchatlaht community of Oclujce earlier in the week turned out to be a positive case.

Contact tracing through the B.C. Centre for Disease Control began on Nov. 21, but this coordinated effort failed to determine if the school visitor was the source of Ehatis’ cluster of cases. This inability points to the larger issue of how much information is shared with First Nations about confirmed coronavirus cases in the vicinity of their communities.

The problem was mentioned in a recent report on discrimination against Indigenous peoples within the health care system by former judge Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond. In Plain Site cites the lack of timely and complete sharing of COVID-19 data with First Nations, something that hasn’t helped the prevalence of infections among Indigenous people. Over the first seven and a half months of the pandemic, Aboriginal people were infected 80 per cent higher than the rest of the B.C. population, according to Turpel-Lafond’s report.

A coalition has been pushing the province to better empower First Nations to protect its members from COVID-19 by sharing more information. Since May, the Heiltsuk Nation, Tsilhqot’in National Government and Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council have called for the Ministry of Health to share where infections are if they are close to a First Nation community, if a positive case has been to a village in the past 14 days, and – for the purpose of effective contact tracing - the name of a First Nation’s member if confirmed to have COVID-19.

The province has been reluctant to share this data, citing the need to protect a person’s confidential information in accordance with the Public Health Act. Health Minister Adrian Dix has also said that disclosing an infected person’s identity could discourage others from reporting to the BC Centre for Disease Control, thereby discouraging someone’s “willingness to engage in the process of the health care system.”

In September the group of First Nation governments submitted a complaint to the B.C. Information and Privacy Commissioner to push the province to disclose more information, but three months later, a decision has not materialised.

Meanwhile, NTC President Judith Sayers questions the emphasis from Provincial Health Officer Bonnie Henry on controlling contagion by isolating cases.

“We don’t really agree with that,” she said, noting the high number of people living in many Nuu-chah-nulth households. “Sometimes in our homes, if you find one [infected] person, all of them are going to be positive because they’ve been around that person for so long.”