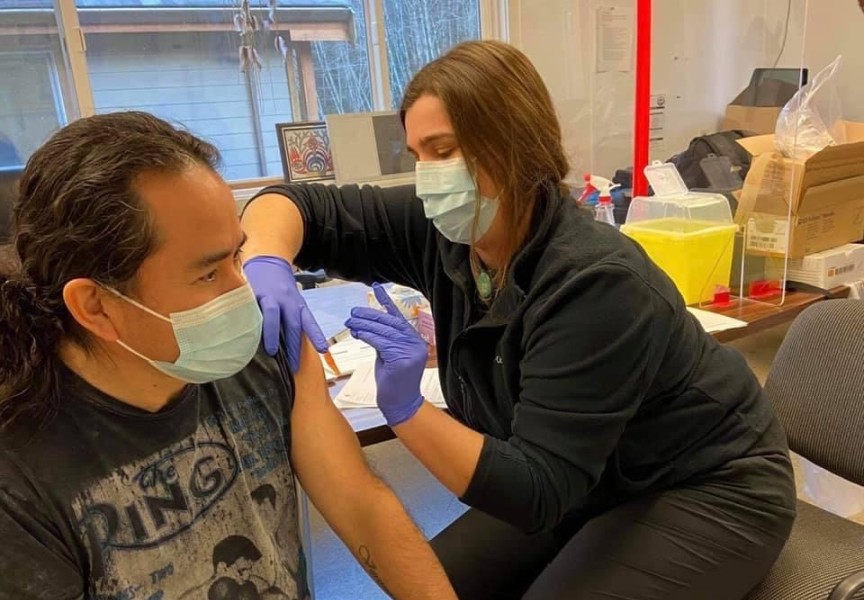

Doctors and First Nations leaders are urging Aboriginal people to put their trust in the health authorities to support the province’s inoculation effort against COVID-19.

Just over a week after the Moderna vaccine was approved by Health Canada, doses were sent to remote Nuu-chah-nulth communities on Jan. 4. Over the first week of 2021 a large proportion of adults in Anacla, Ahousaht, Tsaxana, Kyuquot, Ehatis and Oclucje were given the shot. More settlements on the west coast of Vancouver Island are expected to receive priority attention in the coming weeks due to their distance from medical facilities.

As the second wave of the highly infectious virus continues to spread, leaders are urging those who live in remote locations to get the shot while the opportunity is there – although vaccination is not mandatory.

“We are encouraging people to take the vaccine,” said Mariah Charleson, vice-president of the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council. “My worry is that all the resources that are going into getting these vaccines into rural and remote communities, that’s not going to happen again.”

Based on studies of 30,000 participants, the Moderna vaccine is deemed 94.1 per cent effective in preventing COVID-19 two weeks after the second dose is administered. That second dose is expected to arrive in remote Nuu-chah-nulth communities four weeks after the first shot is given.

It contains molecules that give a person’s cells instructions to build proteins that trigger an immune response to protect from COVID-19.

“When a person is given the vaccine, their cells will read the genetic instructions like a recipe and produce the spike protein,” describes Health Canada. “Once triggered, our body then makes antibodies. These antibodies help us fight the infection if the real virus does enter our body in the future.”

The Moderna doses can be stored under normal refrigeration for up to 30 days, unlike the -70C requirements for the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine that was first approved by Health Canada. This makes Moderna better suited for travel to west coast villages.

But many who live in the First Nations communities that the province has prioritized will be asked to trust a medical system that in the past has them feeling disregarded. An independent report released in late November by Mary-Ellen Turpel Lafond listed widespread accounts of discrimination and racism in B.C. health care, leading many to distrust the professionals they now rely on for vaccination.

“There are people in every one of our communities that will not go see a nurse, they will not see a doctor, because they don’t trust the system,” noted Charleson. “I know people alive that have been tested on in Indian hospitals, and not very long ago.”

Charleson added that the NTC has dealt with this lack of trust by relying on the NTC’s nurses for COVID testing and vaccination, providing familiar faces to those who live hours away from the closest hospital. The tribal council has not been in total agreeance with how the province has handled the pandemic, and continues to push for more people in remote communities to be trained as contact tracers.

Charleson points to the failure of the BC Centre for Disease Control to pinpoint the origin of a December outbreak hitting the Ehattesaht First Nation which infected over one quarter of its on-reserve population.

“It all came tumbling down,” she said. “One of the things we were fighting for was culturally safe contact tracers early on in the pandemic, bringing out the importance of having those people in the community. We saw that with Ehattesaht.”

Another challenge facing the widespread inoculation is mistrust of the vaccine itself. While it can take a decade for a shot to be developed, tested and distributed, the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine was rushed to availability in less than a year. Health Canada lists mild side effects, such as mild body chills, pain where the shot is given, fatigue or feeling feverish after receiving a dose – but health officials insist that the vaccine is the safest means of controlling the coronavirus. The vaccine has not been deemed safe for those under 18.

“No major safety concerns have been identified in the data that we reviewed,” states Health Canada. “As with all vaccines, there’s a chance that there will be a serious side effect, but these are rare. A serious side effect might be something like an allergic reaction.”

Dr. Kelsey Louie, a medical officer with the First Nations Health Authority, does not foresee any long-term side effects.

“I feel quite confident that it’s going to boost the immune system, it’s going to boost the ability to protect your body,” he said. “It think it’s really valuable and really important to protecting our communities. I’m certainly waiting eagerly to being able to receive my vaccine.”