After more than seven months of pushing for the province to share more information with a coalition of First Nations, an agreement on disclosing COVID-19 case numbers has been reached.

Today the deal was announced by the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, Heiltsuk Nation and Tsilhqot’in National Government, which entails Provincial Health Officer Bonnie Henry disclosing the number of COVID-19 cases in communities that are near reserves or treaty settlement lands. For the 14 nations that belong to the NTC, these communities include Bamfield, Port Alberni, Ucluelet, Tofino, Campbell River, Zeballos, Gold River and Tahsis.

Since early 2020 the Ministry of Health has given regular updates on the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases, with tallies for each health region. But without knowing how many cases are in the towns Nuu-chah-nulth-aht visit, First Nations were being deprived of vital information, said NTC President Judith Sayers.

“We have said from the beginning that as governments we need this information to make good decisions on preventing the spread of COVID into our communities and letting our members know when they may need to be extra careful going into towns to do their essential services,” she said.

Now regular updates will be provided to the NTC nations on the number of cases in nearby towns. But the agreement also includes conditions on how much information will be shared. The First Nations are not to disclose the numbers to their members through any publication or announcements; rather councils can advise people which places have a higher risk of contracting the highly infectious respiratory virus.

“We can get to lockdown if we need to and just say, ‘Members, you’re not travelling anywhere, we’ll bring in food’,” said Sayers.

The information provided to the nations does also not show “real time” cases, as numbers disclosed will be based on tests conducted at least six days before, specifies the agreement.

Case numbers are to be made public if they reach 10 in a town with a population under 20,000 over a 28-day period. For larger cities like Campbell River, the threshold for public disclosure is five cases.

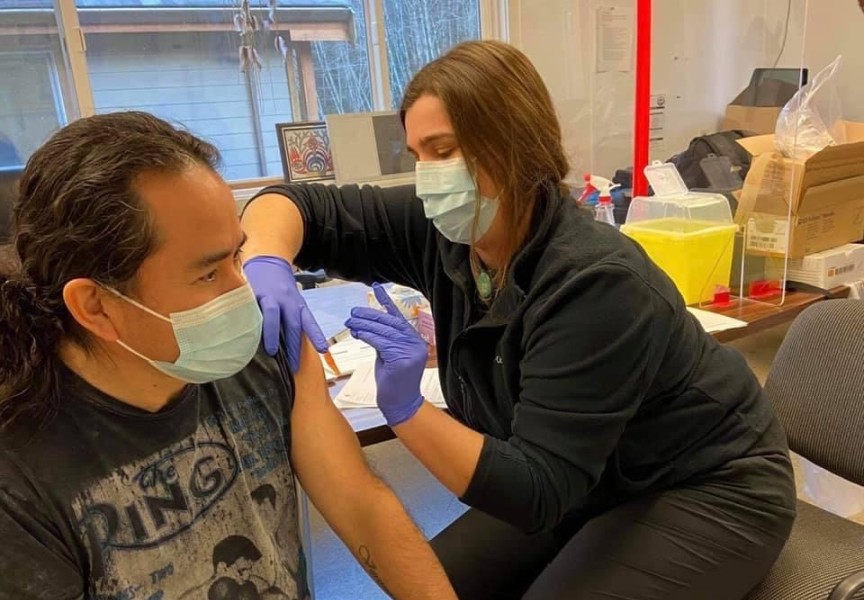

“I recognise that Indigenous communities in British Columbia have been seriously and negatively impacted by historical epidemics,” said Dr. Bonnie Henry in a statement. “My office is sharing information in the spirit of reconciliation, to realise self-governance and self-determination, and to ensure an effective public health response to COVID-19.”

The agreement will provide the coalition of First Nations with more information to protect their members from infection, but it falls short from what was requested since June. The identity of an infected member of one of the nations will not be disclosed, nor will the locations of where a confirmed case travelled to or where the exposure occurred.

Language in the agreement notes that the nations assess COVID-19 risk differently than the provincial health officer, and that the new arrangement is not necessarily satisfactory.

“[T]hey view negotiating this agreement to have been a long and frustrating process,” reads the document. “The nation is of the view that systemic change must occur in B.C.’s healthcare system, including the nation’s view that new structures and protocols that support sufficient and timely information sharing with Indigenous governments during emergencies should be established”.

“It does give us more information, it allows us to do some risk management,” said Sayers. “When people are out there doing their thing - essential services and that sort of thing - they need to know what they’re walking into, to know to be extra careful.”

Since the start of the pandemic the province has tightly controlled information on the specific location of confirmed cases. Previous responses to the coalition’s request have cited the importance of protecting privacy requirements. In December an application to the B.C. Information and Privacy Commissioner was declined, as “sufficient information is already available,” according to the commissioner.

Minister of Health Adrian Dix previously defended the need to keep COVID-19 data close to his chest, suggesting that more public disclosure could discourage others from reporting their illness for fear of discrimination. In January members of the Cowichan Tribes encountered this from local businesses after the First Nation reported an outbreak on it’s reserve.