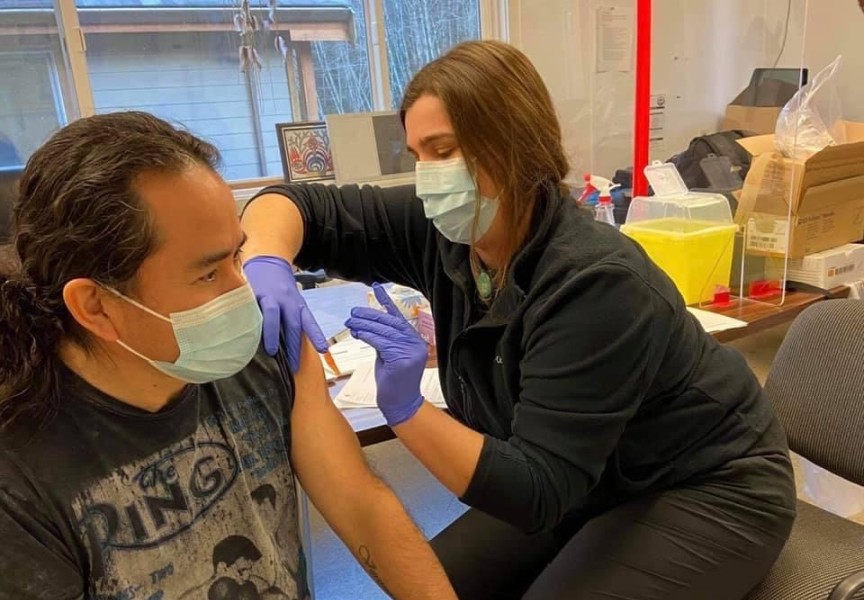

Booster shots will soon be coming to remote Nuu-chah-nulth communities, as health authorities prioritize First Nations that got their first two vaccinations for COVID-19 early this year.

“We will be focusing on communities that have had significant outbreaks,” noted Dr. Shannon McDonald, the First Nation Health Authority’s acting chief medical officer.

While specific locations have not been identified, the province’s new campaign to make the third shot more available raises the likelihood communities that received their first two shots last winter will be among the first to be included in the booster campaign. In Nuu-chah-nulth territory, Ahousaht, Anacla, Ehatis, Kyuquot, Tsaxana and the Ditidaht First Nation’s village on Nitinaht Lake began receiving community immunization in January.

Over the last week of October Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council Vice-president Mariah Charleson was informed by Island Health that community-wide booster shots can be expected this winter.

“They did ensure us that when it comes to our communities it will be done in the same community approach that we have been advocating for from the beginning,” she said.

Booster shots are now available across British Columbia for those who are 70 or older, as well as Indigenous people over 12. In January this plan will expand to everyone else willing to roll up their sleeve a third time, according to a provincial announcement issued on Wednesday, Oct. 27. A third shot is already being offered to residents in long-term care and assisted living homes, as well as vulnerable people living in shelters, according to the province.

“Our vaccines are highly effective,” stated Dr. Bonnie Henry, B.C.’s provincial health officer, in a press release. “However, we are starting to see a gradual decline in protection over time.”

This decline in protection could help to explain COVID-19’s fourth wave, a rising level of infections seen across B.C. since the late summer. The province reports that fully vaccinated people accounted for 35.3 per cent of infections, while those without any shot made up 58.2 per cent of cases tracked Oct. 20-26. From Oct. 13-26 those not vaccinated made up 68 per cent of hospitalizations with COVID-19, while the fully vaccinated accounted for 26 per cent, according to the B.C. Ministry of Health.

“It’s not just about the vaccine isn’t working, it’s about we need the vaccine to work better to battle the circumstances many of our communities live in,” stressed McDonald. “We also know that the playing field isn’t level among all the citizens in the province. There are people who have chronic disease, who live in housing with 10 other people where if one person comes in who’s active in COVID, that chances are that everyone else in the household will be exposed.”

Remote Nuu-chah-nulth communities were among the first in B.C. to receive their first two shots early this year. At that time public health guidelines said the ideal interval between doses was 21 to 28 days, but this advice has since changed.

“We now know that a longer interval between those two doses actually gave people an advantage in terms of an immune response,” said McDonald. “Now that we’re starting to see cases in people who have been double-vaccinated, when we looked at those cases, we’ve seen a pattern of people who received those early doses with short intervals. So the planning for the booster dose is around who got it first and who got the shorter interval.”

First Nations remain at a higher risk of contracting COVID-19 than the general population. According to data collected from Island Health from January to the end of September this year, there were 1,268 cases of COVID-19 among Aboriginal people, while 6,466 infections affected other residents of Vancouver Island. This means that 16 per cent of COVID-19 infections on the island this year affected Indigenous people - a rate significantly higher than their proportion of the population, which is approximately five per cent.

Over the first nine months of 2021 there were 95 hospitalizations of Indigenous people with COVID-19 on Vancouver Island, 86 per cent of which were not fully vaccinated. Thirty-two of these cases went into intensive care, while 96 per cent of these patients had not received both doses, and of the 16 COVID-related deaths to Aboriginal people over this period, 88 per cent were not fully vaccinated, according to Island Health.

Vaccination rates among B.C. residents 12 and older have grown to 90 per cent with one shot, and 85 per cent with two doses. But this is significantly lower among Aboriginal people, notes McDonald, as this portion of the province has vaccination rates of 77.5 per cent and 66.8 per cent with two and one dose respectively.

“We still have lots of work to do,” said McDonald.

She reflects that one of the biggest lessons over the pandemic has been to listen better to the concerns of individuals, including those who are worried about the negative effects of vaccination.

“I’ve had a lot of conversations with people who have lots of anxieties and fears about getting the vaccine for lots of different reasons,” said McDonald. “They’ve had a reaction to a vaccine in the past, they don’t trust anything in terms of an experiment…those are the kinds of concerns that people have. I need to acknowledge them and talk about why they are not true.”