One week after being diagnosed with bone cancer, Leo Manson Sr.’s nose started to bleed profusely while visiting his son in Ty-Histanis, a Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation community on Vancouver Island.

His wife, Maxine, immediately brought him to the Tofino General Hospital before he was transferred to the Nanaimo General Hospital for further care.

After being awake and by his side for nearly 24-hours, Maxine said she left him in the hospital’s care to get some rest.

Unable to breathe properly and disorientated from the loss of blood, Manson sat up on the edge of his hospital bed, and intermittently stood up to catch his breath. This allegedly prompted hospital staff to restrain him by strapping Manson to his bed.

When Maxine returned, she said she found her husband’s arms, stomach and back covered in dark bruises.

The straps were placed over his hips where Manson has “tremendous pain,” disallowing him from laying down comfortably, Maxine said.

“They threw him against the wall [and] bent his wrists back,” she said through tears. “They were really roughing him around.”

Because of Manson's bone cancer, Maxine said the doctor was concerned his body was going to have to fight even harder to heal from the bruises.

“He’s going to have the fight of his life with this cancer,” she said.

On May 25, Maxine filed a complaint against the hospital through the First Nations Health Authority (FNHA).

“I don’t ever want to see another native person be treated like that,” she said. “We’re just people too – we’re humans. We just want to be treated with respect. This never should have happened in a hospital when someone is so vulnerable.”

The decision to restrain a patient is made “based on a variety of factors and is done at the clinical judgement of the care team to ensure the safety of both the patient and staff,” Island Health wrote in an email.

Despite this, Island Health said it acknowledges that Manson did not receive culturally safe care.

“We are deeply concerned about the impact of this experience on the patient and their family,” Island health said. “We have connected with this patient’s family to listen and learn from their experience, and these conversations are ongoing.”

Island Health said they are also in dialogue with leadership from the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation to ensure their response “goes beyond words and includes meaningful actions.”

Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council Vice-President Mariah Charleson said B.C.’s health care system has “a long way to go” before Indigenous populations feel safe accessing care.

“It's really troubling to know the reality that our people are still facing racism in the healthcare system,” she said. “We really need to look at trauma-informed practice and trauma-informed care so that our people are treated like human beings.”

In between visits with Manson on May 24, Maxine was told she could wait in the hospital’s cultural gathering area.

Upon asking for directions to the gathering area, she said she was told to, “get on your horse and buggy and go around to the main entrance of the building,” by an ambassador.

“We get remarks like that every day,” Maxine said. “That’s what we go through every day.”

Discrimination in Canada’s healthcare system is not a new conversation.

In 2020, the In Plain Sight report identified “widespread systemic racism against Indigenous peoples” in B.C.’s health care system which resulted in a range of negative impacts, including death.

Led by independent reviewer Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond, the report made 24 recommendations to address Indigenous-specific racism.

Over a year after the recommendations were made, Turpel-Lafond said there have been “some” signs of progress but that they don’t go far enough.

Stories shared with the FNHA quality care and safety office “demonstrate there is an urgent need to address racism and discrimination in our health care system,” the health authority said.

“Many Indigenous individuals who report their experiences accessing health care tell us about the poor treatment they receive,” FNHA said. “Although every story that we hear is different, there are common themes, including, challenges with quality care and treatment, personnel, discriminations and Indigenous-specific racism.”

Transforming the health care system will require systemic alterations and behavioural change from health providers, FNHA added.

Manson’s son, Tim, said a First Nations support worker should have been there to support his father.

“A liaison worker can only be there when they’re called,” he said.

If a patient is disoriented, they don’t always have the capacity to call a liaison worker, he added.

Island Health said it acknowledges systemic Indigenous-specific racism occurs within its health authority.

“Our patients and communities can be assured we are taking action, and the steps that we are taking will continue to be guided by Indigenous leaders and communities,” Island Health said.

Since August 2020, Island Health said cultural safety and humility training has been mandatory for all staff, physicians, midwives, and nurse practitioners working in all Island Health emergency departments.

Maxine said she’s concerned that training doesn’t extend to security staff.

Currently, there is one Indigenous liaison nurse employed at Nanaimo General Hospital and a second will be included through a contract with Snuneymuxw First Nation, according to Island Health.

A renewed Vancouver Island Partnership Accord was signed in May 2022 between FNHA, Island Health and the Vancouver Island Regional Caucus, which represents the 50 nations on Vancouver Island. It re-established the commitment to improve the health and wellness outcomes of all First Nations people in the Island Health region.

“The accord speaks to reciprocal accountability that emphasizes collaboration and collective action as a way of accelerating improvement to First Nations health and wellness,” the FNHA said.

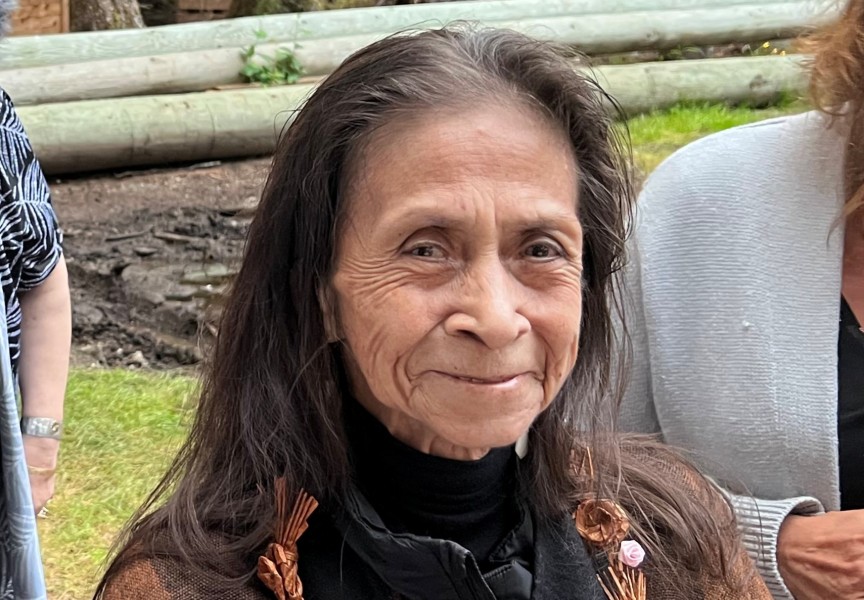

Maxine described her husband as a “very humble” and “quiet” man.

“[He’s] always working for the people at home – no matter what situation they're in,” Tim described. “He’ll do his best to accommodate anybody and everybody.”

By sharing Manson’s story, Maxine said she hopes no one else will have to suffer in the same way.

“I’ve always stood up for the little people,” she said. “If they can’t speak, I’ll speak for them.”