The Indigenous Healthy Life Trajectories Initiative proposes to be “Canada’s first long-term study following a large cohort of young children and their families over time,” according to an update by the project team. The study has completed two preliminary two-year phases, with funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Now a more extensive proposal has been submitted to the funder, totaling $14 million to support six years of study involving 14 Nuu-chah-nulth nations as well as First Nations in Alberta that include the Cree Nations of Maskwacîs, and the Cree and Dene nations of the Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo.

With Lynette Lucas, director of health for the Nuu-chah-chah Tribal Council, as the principal investigator, the project update stated that “health and wellbeing are the result of long-term access to physical, spiritual, emotional, nutritional and social resources”. Topics of interest have been identified by the communities involved, with attention to cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity and mental health.

If approved, the next phase of the study entails women of child-bearing age volunteering to participate, answering to invitations sent across Nuu-chah-nulth communities as well as the First Nations in Alberta.

“The main goal for the project is to identify the factors that provide resilience to children to face life challenges, so that they can develop strong and be ready for all the challenges in life,” said Pablo Nepomnaschy, a professor of Health Sciences at Simon Fraser University, which is working with the NTC on the long-term project. “Our findings will not only help Nuu-chah-nulth children, Cree children and Maskwacis children, but eventually be applied to other Indigenous children.”

“For the women who do give birth, we evaluate them in a number of ways during the pregnancy,” explained Jeff Reading, an SFU professor in Health Sciences. “When they give birth, their children are enrolled into a study where we look at the long-term impacts of optimizing their health and wellbeing. We call it developmental trajectories; it goes through life stages.”

“It’s more than just the mother’s activities, it’s the mother’s environment. Does the mother have the right nutrition? Does the mother have enough social support?” added Nepomnaschy. “Early exposures during development, even from conception onward, have huge effects on the health and wellbeing of the child. The earlier the exposure, the stronger the effect and the more effects there are.”

The initiative follows other health studies that have usually painted a grim picture of Indigenous people’s wellbeing. Presented by the First Nations Health Authority and the Provincial Health Officer in 2018, the Indigenous Health and Well Being report presented an average life expectancy of 75 among B.C.’s Aboriginal people, eight years younger than other residents in the province. That report also cited a suicide rate among First Nations youth that was triple that of others in B.C., with double the incidence of infant mortality and higher rates of diabetes.

For over two decades, Reading has worked to get a more extensive study off the ground that better involves and benefits First Nations.

“A lot of research done on Indigenous people is a snapshot that talks about how unhealthy people are,” he said. “What we’re trying to do is a longitudinal study, which is sort of a video looking at how to model wellbeing, rather than modelling pathology.”

Reading referenced the damage done by what is commonly known as the “bad blood” scandal, in which over 800 samples were taken from Nuu-chah-nulth-aht in the 1980s with a promise to find better treatment for rheumatoid arthritis. But without the participants’ permission or knowledge, it was later discovered that these samples were taken to the United States and elsewhere for genetic anthropology studies and other experiments.

“Now it’s a question of how we can do research led by Nuu-chah-nulth,” said Reading. “There’s no misuse of the data and the samples, so it’s under a very strong ethical framework.”

“We are here to do this because the community chose these goals. Everybody is invited to participate to the extent that they are interested in the study,” noted Nepomnaschy. “They can even decide that they don’t want their data used anymore, or their samples are to be destroyed, and that is absolutely revolutionary. It’s a type of research that has not been done so far.”

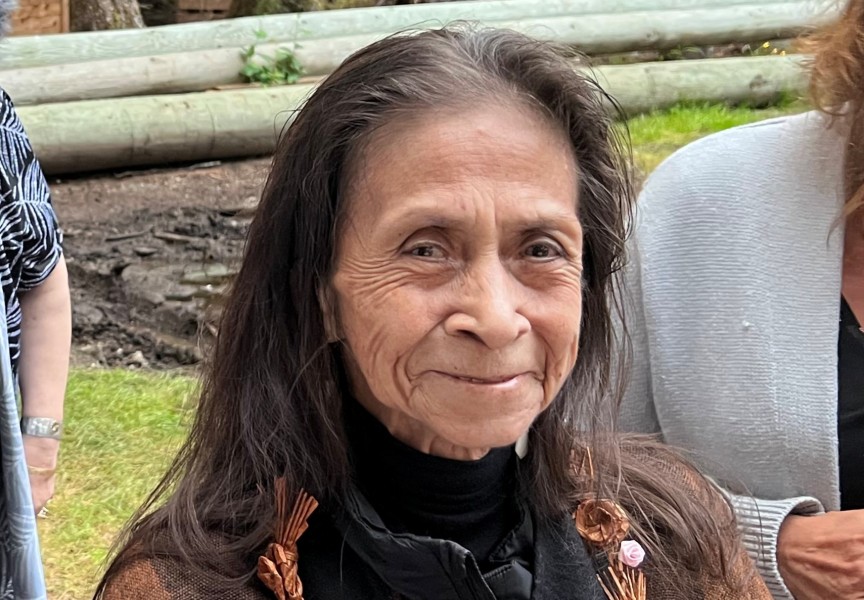

Since the study began planning and consultations in 2017 Geraldine Tom has served as a Nuu-chah-nulth advisor. She hopes that the long-term project will help to break a cycle of shame among First Nations that was instilled in residential schools, but continues to be perpetuated by authorities and service providers.

“It is a big issue still,” she said. “Some caregivers, police, shame us. We want to break that cycle of that.”

“The elders have a central role in advising us of what kinds of interventions are going to be reclaiming health, because a lot of times, well-meaning people who are doctors and nurses, they’re focused on disease, treatment and care,” said Reading. “What we’re focused on is trying to understand the mechanisms. What causes diabetes in middle age or in your 30s? Part of that is what happens in very early life.”

Tom hopes that within five years the study will help to give service providers a better understanding of Nuu-chah-nulth ways so that they can more effectively help communities with their issues.

“We cannot move in reconciliation without understanding along the way,” she said.

More information about the Indigenous Healthy Life Trajectories Initiative can be obtained from Laurel White, the NTC’s project coordinator, at laurel.white@nuuchahnulth.org or 1-250-724-0202, ext.9.