DFO scientists are drawing a direct line between climate change and fish population decline in what is shaping up to be one of the worst years on record for wild salmon.

Normally sunny, pre-election announcements out of Ottawa have taken on a darker tone in recent weeks as the department grapples with an emergent threat at Big Bar on the Fraser River.

None was grimmer than an Aug. 22 gathering that included release of the 2019 State of the Canadian Pacific Salmon, the first briefing of its kind, delivered by DFO scientist Sue Grant.

“The planet is warming and the most recent five years have been the warmest on record,” Grant said, repeating the now-familiar global scenario, a trend with a profound impact on animals that thrive in cooler waters.

Arising from a 2018 workshop among scientists, the report concludes Pacific salmon and their ecosystems are already adapting to climate changes, some not as well as others. While there are multiple and complex factors contributing to the overall decline, the required remedy could not be clearer.

“The extent that we are able to curb our CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions will determine the magnitude of future warming,” the report states. “There is still time to moderate climate change impacts on salmon and people.”

Each of the five DFO-managed species of Pacific salmon faces climate-related challenges:

- Chinook are declining throughout their range.

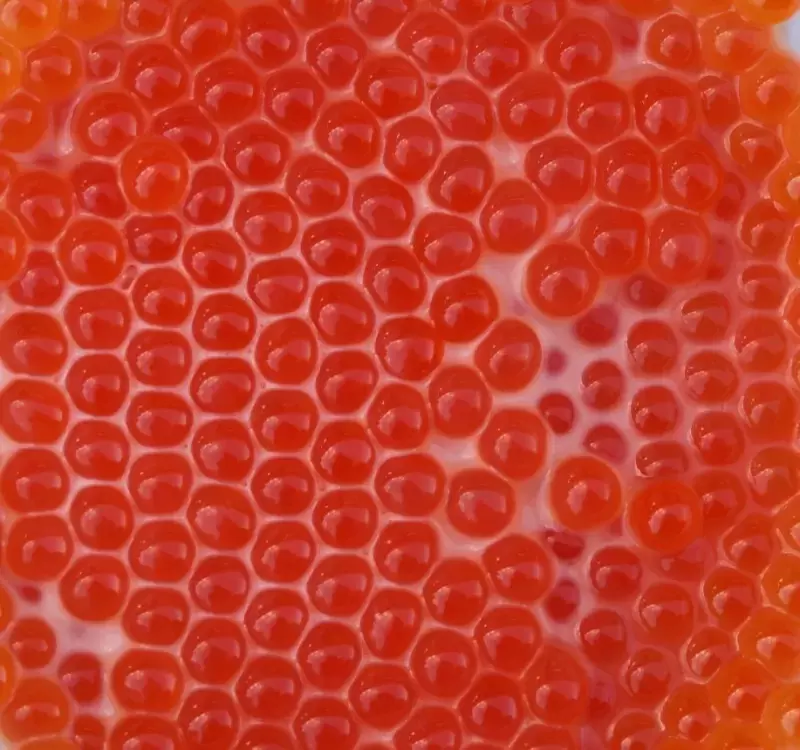

- Southern sockeye populations are dropping to a point where some face imminent extinction.

- Southern coho populations are declining.

- Pink are showing some declines in the south.

Healthy salmon populations tend to spawn further north and spend less time in freshwater, but their freshwater habitats are relatively undisturbed, the report concludes. Another major factor is warm ocean temperatures that decrease production of larger, energy-rich zooplankton, contributing to poorer marine survival for salmon.

The full report can be found in e-book form at www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/species-especes/publications/salmon-saumon/state-etat-2019/ebook/index-eng.html

“There is no question that climate change is having a significant impact on our salmon … 2019 has been a particularly difficult year for wild salmon,” said Fisheries Minister Jonathan Wilkinson, summing up the report. “Part of any realistic plan to protect and ultimately restore key salmon stocks must include a comprehensive and aggressive plan to reduce carbon emissions.”

Some of those in attendance were clearly frustrated with the pace of government action.

“We have declared a state of emergency with regard to the rock slide on the Fraser River and it’s being ignored,” shouted Neskonlith Chief Judy Wilson, secretary-treasurer of the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs. Wilson then questioned why the federal government is pushing ahead with the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion given its conclusions about climate impacts.

NTC President Judith Sayers said the report, a harsh wakeup call, represents the first time DFO has been so clear in attributing species decline to climate change. With warmer summers, temperatures have been elevated in the Somass River for years and should have been addressed long ago, she said.

“Why has it taken so long? They should be focused on strategies,” she added, noting that no First Nation input went into the report.

“They need to be taking immediate action and adapt to climate change,” she said. “They seem to go about this as though it were business as usual.”

Jim Lane, NTC southern region biologist, said the report is noteworthy, although not so much for its assessment of the stocks.

“I think it’s more significant that they are starting to recognize that climate will have an impact on a number of populations and that certain populations are probably going to be more vulnerable to habitat changes,” Lane said. “As an organization, they’re still struggling with how to deal with it.”

Citing the Somass as an example, he pointed to a gap in knowledge about the extent of pre-spawn mortality. In the past, there were multiple surveys taken in the main tributaries of Sproat and Great Central lakes. The practice ended not long after the first warm-water event in the Somass River in 2004. Only two fish counts continue at Sproat Lake and Stamp Falls.

“We don’t do that,” he said. “Consequently, we’re not accounting for pre-spawn, sub-lethal effects of warm water on reproductive capacity of those fish.”

Somass stock assessments have been cut back as well to a single assessment, a test fishery by the seine boat Nita Maria.

Despite steady declines in southern populations of Pacific salmon, Lane is optimistic about the resilience and adaptability of salmon in general.

“Salmonids are incredibly adaptive,” he said. “They can be generations distant from the home population and yet they adapt readily to location.”

Wilkinson has been busy the last few weeks, re-announcing projects approved for funding through the Salmon Restoration and Innovation Fund. The list of 23 projects so far approved does not include any on the Island’s west coast, an omission duly noted by Nuu-cha-nulth leadership.

Uu-a-thluk, the NTC fisheries department, made five applications to the fund. One was rejected and four were deferred to the next intake date promised this fall.

What would top Lane’s list of measures to rebuild wild salmon stocks?

“It would be getting a much better hold on what’s being harvested,” he said. “Much more resources directed at management and rebuilding of wild populations.”

Along the west coast of the Island, a major opportunity exists to boost sockeye populations that, although relatively small, are important to Nuu-chah-nulth nations, he said. Rebuilding those fisheries could provide greater flexibility in allowing larger stocks to recover. He listed a few examples, including the Henderson Lake sockeye run, which has declined dramatically, or Kennedy Lake sockeye, once the largest among Island stocks.

Sayers believes the State of Salmon report presents a clear call to action.

“If we continue on with what we are doing with more greenhouse gases, I think it’s going to be difficult no matter how healthy the stocks are,” she said. “The mitigation must be done sooner. There are just some conditions they just can’t live in.”

The possibility of watching wild salmon stocks decline from endangered to lost is too disturbing to contemplate.

“We’ve got to do more about climate change,” Sayers said. “This is integral to who we are.”