Editor's note: This article contains material which may be disturbing to some readers

Through over a year of research that included ground-penetrating radar and extensive analysis of testimonials from former students, an investigative team has announced that at least 67 children died while attending the Alberni Indian Residential School.

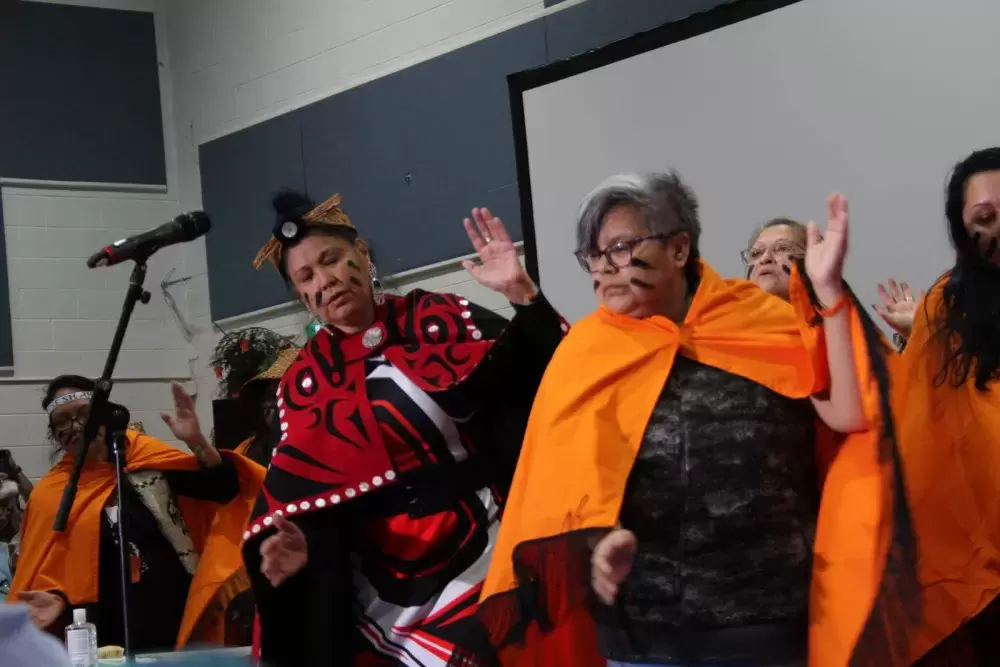

This news was announced today by the Tseshaht First Nation before a packed Maht Mahs gym, itself a former structure built for the residential school, which operated for nearly a century in Tsehshaht territory near the western bank of the Somass River. From 1893 onwards, children from over 70 First Nations attended the institution as part of Canada’s assimilationist residential school system. AIRS was run by the Presbyterian then the United Church of Canada, before the federal government took over operations for the last five years before the doors were closed in 1974. The project’s tally is more than double the 29 AIRS deaths that were previously listed by the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation.

Besides multiple reports of physical, sexual and spiritual abuse, for generations survivors and the Tseshaht community have been aware of children dying at the institution. Following the news of 215 unmarked burials indicated at the former site of the Kamloops Indian Residential School in May 2021, Tseshaht launched ʔuuʔatumin yaqckʷiimitqin (Doing it for our Ancestors), a multi-phase project that aims to “shed light on the truth, history and the need for justice,” according to the First Nation.

On Feb. 21 findings from the first phase of this undertaking were released, the result of a combination of analysing historical records, statements from survivors of the residential school, above-ground laser LiDAR scanning and ground-penetrating radar. This radar scanning identified 17 possible burial sites of former students, which was obtained by radio frequencies collecting data by bouncing off of various changes in the earth.

“In the data we look for things that are shaped or have the right size to be burials,” explained Brian Whiting of GeoScan, which conducted the ground scans. “We look for a break in the layers that suggests a grave shaft, and inside that break in the layers are there reflections that could be from a coffin or from material breaking down over time.”

Although Whiting cautions that only archaeological excavations could completely confirm a child burial – something that the Tseshaht will not undertake for this phase of the initiative – the process of identifying likely graves includes combining data and ruling out other underground objects.

“We always try to rule out more normal causes, natural features like logs and roots and so forth before making the call of something being a possible grave,” Whiting said.

The project team identified 100 hectares of land where former students could have been buried, but GeoScan has so far only covered 12 per cent of this area through its drone-operated LiDAR scanning and ground-penetrating radar. Tseshaht Chief Councillor Ken Watts said that federal funding will be necessary to undertake the next stage of the project.

“We’ve been able to do what we can with what we have, but they definitely have to step up,” he said. “We are not in a place to carry all of it on our own source revenue.”

As the results were announced 67 small stuffed bears covered a section of the floor, a reminder of the next task for ʔuuʔatumin yaqckʷiimitqin. Each of these toys are to be delivered to families of the children who never left the confines of the residential school, along with information gathered from the project about the victims.

But this might not be yet possible for all of the families, as some victims are only identified by a first name, said the project’s lead researcher Sheri Meding, while others don’t have a name anyone can recall.

“We know the names of some of the students that died,” she said. “We know what age they were when they died, what they died of.”

“Overwhelmingly, the cause of death was due to medical conditions,” she continued. “Conditions that were very clearly inadequate conditions, unhealthy conditions at the school.”

But accounts from former students also spoke of witnessing a pupil being killed, small coffins being taken out of the building at night, female students getting impregnated from staff and forced abortions.

“And also witnessing newborns and aborted fetuses being disposed of in the incinerator,” added Meding.

Although survivors of the residential school have for many years carried stories of this incinerator, Watts said it’s yet to be determined how its location can be identified.

“How do we actually verify that through other technology? That will have to be coming in the weeks and months ahead,” he said, noting complications due to development on the Tseshaht reserve after AIRS closed. “One of the big difficulties of our community is the work that’s happened after. At the site we have new homes around the area, we have a lot of different development that’s happened. Nothing has ever come up in that development where we’ve been concerned, but to identify that site where that individual incinerator was, the technology that can or cannot be used remains to be seen.”

Despite the trauma that resurfaces from disclosing such disturbing information, AIRS survivor Charlie Thompson was relieved that what he has known his while life is being widely publicized.

“It lifts up my spirit,” said Thompson, who had an uncle who died at the institution. “We know, as a family, that our uncle may be part of the number that came up today.”

Charlie’s brother Jack Thompson also attended AIRS and spoke at the event. He mentioned police who caught students after they escaped.

“The police have to be held accountable for what they done. They never listened to the students when they told what was happening to them,” he said. “There cannot be reconciliation until the truth is known by everyone.”

Looking ahead, the Tseshaht are undergoing fundraising for a memorial at the former residential school site that lists every student who attended.

The First Nation also plans to tear down Caldwell Hall, which formerly served as a student residence. The old AIRS building is currently being used by the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council.

“There’s people who won’t even come to our community because that building is still standing there,” said Watts. “We plan on tearing that building down. We’ve told Canada that they need to step up, they need to fully fund the teardown of that building.”