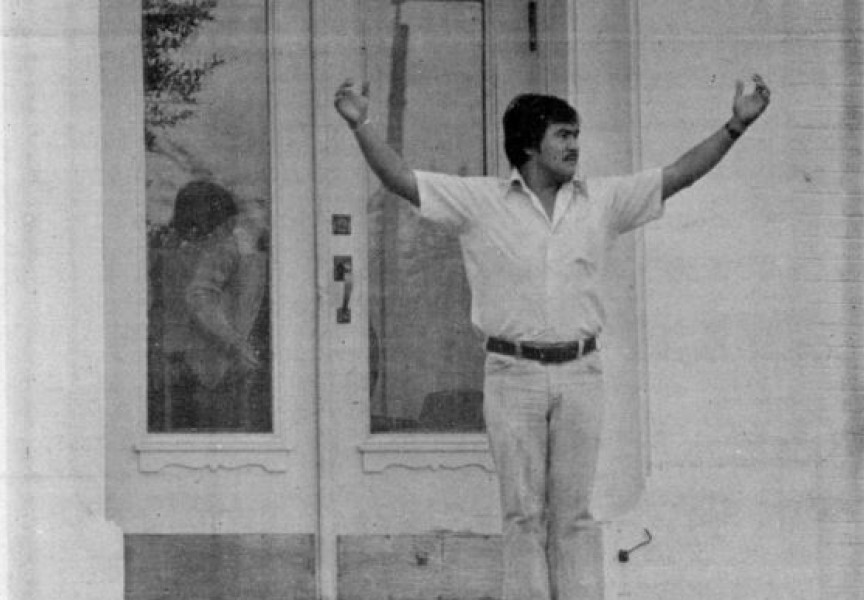

It was nearly 30 years ago that Art Thompson spoke before the Port Alberni courthouse, after the sentencing of the former dormitory supervisor who had terrorized him and others at the Alberni Indian Residential School.

“It’s not our shame,” said the residential school survivor on March 21, 1995. “I want to encourage all of you to have the strength to tell your story.”

The trial resulted in Arthur Henry Plint being sentenced to 11 years for 18 counts of indecently assaulting young boys who attended the residential school. During the trial Thompson was sworn in using his traditional Ditidaht name of Thlop-kee-tupp. During his testimony Thompson stood facing Plint for 45 minutes, detailing the years of abuse at the hands of the former dorm supervisor, according to a Ha-Shilth-Sa article from the time.

“You didn’t care for us, you abused our culture,” said Thompson in the courtroom. “You can’t face reality. You can’t look me in the eyes and tell me I’m wrong. You remind me of the genocide of our people.”

In his sentencing Justice Douglas Hogarth called the residential school system “nothing less than a form of institutionalized pedophilia.”

That trial and the stand that Thompson took was to become one of the early sparks that would eventually inflame into the Truth and Reconciliation Commission - bringing about a national reckoning for the forced assimilation and abuse imposed on Canada’s Indigenous children for over a century.

Thompson died due cancer in 2003 at the age of 54, but his daughter is now carrying on his story with a new book. Largely based on Thompson’s testimony from court cases, The Defiant 511 of the Alberni Indian Residential School presents an “incredibly graphic” account of his time at the institution from the ages of 5 to 14, said its author Evelyn Thompson-George.

The book’s title comes from the number that Art Thompson would be addressed as over his years in the institution.

“When you entered into the residential school system, your name was actually replaced with a number,” said Evelyn, whose book underwent multiple drafts over her two years of writing it, starting with a voluminous 29-chapter first version. “My first draft of this memoir is basically the court documents completely rearranged.”

For Evelyn the process began in the wake of news that came out of Kamloops in May 2021. Ground penetrating radar analysis undertaken at the former site of the Kamloops Indian Residential School discovered approximately 200 underground forms that were consistent with unmarked burials. This awakened the country to the likelihood that hundreds of children died and were secretly buried at the institution, setting off a wave of other radar investigations at former residential school sites across Canada. As discoveries of more likely burials continued, the news finally confirmed what residential school survivors had known for their whole lives: that a countless number of children were buried and never brought home.

“Our history was being shared nationally, and I couldn’t help shake my head in frustration,” recalled Evelyn, who felt the need to bring her father’s voice back into the public eye.

She admits that the writing process took its toll, and brought about a period of depression. Evelyn became aware of how she was taking on her father’s suffering when she tried to play with her own young children.

“It was hard to walk away and play with them, because all I could see was my dad,” she said.

Evelyn hopes that the book can be used in high school and university courses to progress the public’s understanding of the residential school system.

“For me, it was kind of like bringing him back to life with this book,” she said. “It’s exactly what he would have wanted.”

Art Thompson was also a widely recognized artist, whose work included designing batons and medals for the 1994 Commonwealth Games in Victoria.

“I think being able to bring the culture to light rather than focusing on something so horrific, I think that very much helped him,” reflected Evelyn of her father. “The healing process made him become an advocate for Canada as well.”

“I knew Art was damaged when we got together,” said Evelyn’s mother, Charlene Thompson. “I knew he went to the residential school and he fought so hard not to get better, and things just got out of hand. He made that decision to go to treatment.”

“He started his journey in a drug and alcohol recovery centre,” said Evelyn.

“Oh my god, he worked so hard on himself,” added Charlene.

Charlene had been studying in a writing course when Thompson was preparing his impact statement for the Plint trial. She recalled pushing her husband to be descriptive in what he went through at AIRS.

“I felt the best impact you could have on a judge or in the courtroom was write explicitly what happened,” she said of Thompson’s testimony. “You could shut your eyes and visualize what was happening to Art.”

Published by Friesen Press, The Defiant 511 of the Alberni Indian Residential School is 162 pages and costs $21.99 for a paperback copy. It is available at Indigo-Chapters, Amazon.ca and other book retailers.