“If we lose the herring we will have no salmon!” said Simon Lucas at a Nuu-chah-nulth fisheries meeting more than 30 years ago. Nearly four years after the Hesquiaht elder’s passing, Julia Lucas recalled how passionate her husband was about Nuu-chah-nulth-aht’s right to harvest and to manage fisheries in their respective territories.

She said it was Simon who tabled a motion at an NTC fisheries meeting that the nations challenge DFO in court to assert their rights to harvest and sell fish. After more than a decade in the courts, five Nuu-chah-nulth nations are celebrating an April 19 decision from the B.C. Court of Appeal. The unanimous decision eliminates restrictions previously placed on how the nations should harvest and sell seafood from their territorial waters off the west coast of Vancouver Island.

Hesquiaht elder and fisherman Stephen Charleson hopes this will change how the fisheries have gone for his community over the last generation.

“For sure it was a dismal feeling to be a fisherman in the 1990s and 2000s,” he said. “By the time the court case was being contemplated I was hardly fishing at all.”

Charleson pointed to exclusionary DFO policies that pushed Indigenous fishermen out of the industry.

“The seasons were starting to get shorter and shorter and the allocations were getting smaller and smaller,” he recalled.

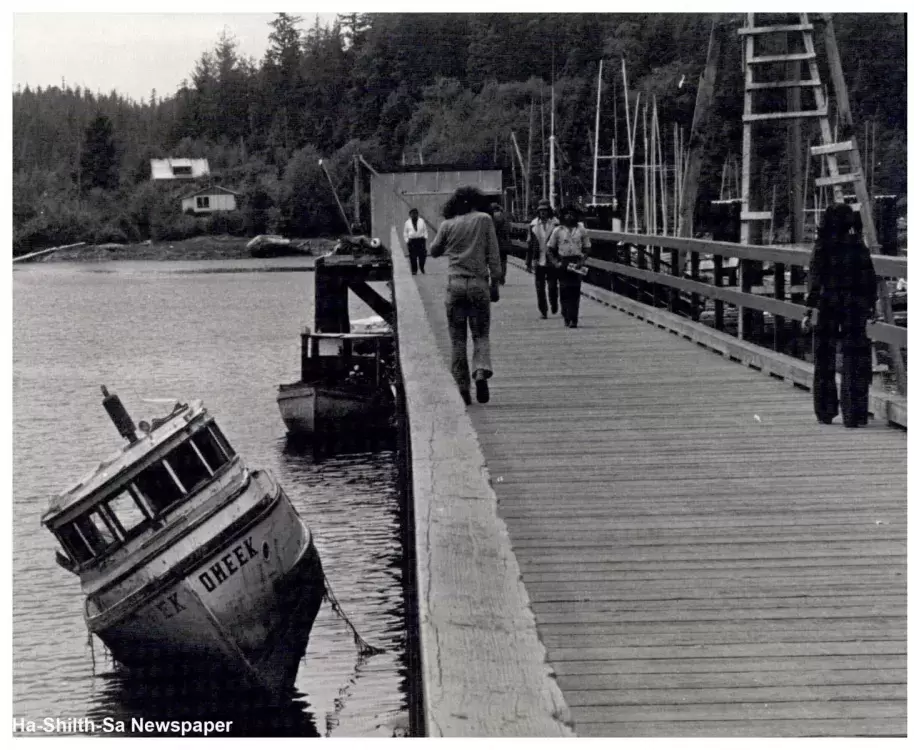

As each year went by there were fewer Nuu-chah-nulth boats tied up in the villages.

“Most of us were fishermen who didn’t really chase the big loads,” he told Ha-Shilth-Sa. “We were happy to get by comfortably year in and year out.”

But DFO began to change the licensing and allocation systems in favor of the larger commercial fishing vessels.

Jon Manson, 43, of Tla-o-qui-aht said he had his own small boat by the age of 12 to fish off of Long Beach, selling his catch to the local fish plants. Manson said he only made it to Grade 9, opting to earn a living starting on his 16-foot boat.

Manson said his father used to have an A license, allowing him to fish all species, but it got taken away with the new licensing and allocation rules. Manson said his father’s license was given to larger, commercial fishermen.

“To be eligible for species like halibut, for example, you had to have a certain amount of poundage in the previous years in order to be allowed to fish for them,” Charleson noted. The same ruled applied for all species.

Charleson’s boat, the Sashmaray, was a combination troller and gillnet vessel. Charleson had to choose one or the other under the new rules, along with an area to fish in. Gone were the days when fishermen could go in other zones under the new DFO rules.

“There was a whole slew of new rules like that combined with a whole bunch of new paperwork and license fees,” said Charleson.

“It became too much after a while and I was losing interest in commercial fishing,” he added, saying that his boat became simply a home-use fishing boat before he gave up in 2005 and beached her.

But Charleson said he maintained hope throughout the years while the fisheries court case dragged on through the appeals that followed.

“I had high hopes that were dashed again and again with DFO’s appeals and Canada’s stance and refusal to honor the court decisions until the last one, last week,” he said.

Management for a Living Hesquiaht Harbour

In the meantime, Hesquiaht people saw commercial harvesters setting crab traps and fishing herring and salmon in their remote home of Hesquiaht Harbour, effectively wiping out what was left of the natural resources.

“They closed down Hesquiaht Harbour to save the fish,” Julia recalled.

According to Charleson, who formerly served as elected chief, his people launched a program called Management for a Living Hesquiaht Harbour back in 1992 after the people passed a motion to protect their resources at a band meeting.

“It was originally a motion regarding logging in the territory,” Charleson said.

The people wanted logging to stop in their territory until they could figure out how to repair damages to their mountainsides and creeks, which became destabilized due to forestry and poor road design. The landslides were destroying salmon habitat.

“The logs were disappearing off the land and we were being left to clean it up while we watched the herring, clams, spawning beds being destroyed and our livelihoods and food sources irrevocably lessening and disappearing,” Charleson added.

Manson noted that millions of dollars have been spent over 30 years on watershed rehabilitation efforts in Clayoquot Sound. The goal was to repair salmon habitat destroyed by logging practices of the past in an effort to increase critically depleted wild salmon stocks. Charleson says Hesquiaht is also working on repairing habitat in their territories and both note that it isn’t making much of a difference. Manson believes the nations need to work to restock the creeks through salmon hatcheries.

Besides putting a stop to industrial logging in their hahulthi, the Hesquiaht management plan demanded the commercial closure of herring, clam, geoduck, sea urchins, crab and any fin fish in Hesquiaht Harbour.

“Sports fishing was added to the list, whether it was in the salt water or in the creeks and lakes,” said Charleson.

For about a decade the closure remained in place while the Hesquiaht collected data and built on research. They reviewed recorded information from elders of the past and hired a western scientist who helped them study and plan for the protection and renewal of their natural resources.

A resurgence of wildlife

In the decade that it was closed to commercial harvesting, Hesquiaht Harbour residents noticed an abundance of birds that came back. Charleson attributes that to the growing number of herring returns.

“It has attracted a lot of birds and mammals during the spawning season from January to April,” Charleson noted.

He went on to say it is a noisy time of year with eagles, sea gulls, cormorants, scoters, loons, seals, sea lions, and grey whales that converge in the area.

“Sometimes hundreds of grey whales are in the harbour from February to the end of March during herring spawn,” he said.

In the fall, when the salmon return to spawn, sea gulls and eagles come back along with bears and wolves.

But the resurgence of the once extinct sea otter has meant no more crab or clams in Hesquiaht for the past 20 years since the predator began feasting there.

Julia Lucas said the protection of natural resources was so important to past leaders like Simon Lucas, George Watts and Nelson Keitlah that one time her husband was summoned to sign court documents while he was on a fishing trip.

“He was fishing off of Ucluelet with our son Linus when George (Watts) sent a plane there to get Simon to Vancouver to sign the documents,” said Julia.

“He was there and back in Ucluelet on the same day,” recalled Linus Lucas.

Ahousaht harbor filled with boats

Julia Lucas, an elder herself, was called to testify in the fisheries court case. She said the court wanted to hear how fishing was in previous generations.

At one point, the judge and lawyers arrived in Ahousaht to hear testimony at the Thunderbird Hall. The court heard elders testifying about how the people lived on fish.

Julia, who is originally from Ahousaht, said she was asked by the court how her father and uncles fished.

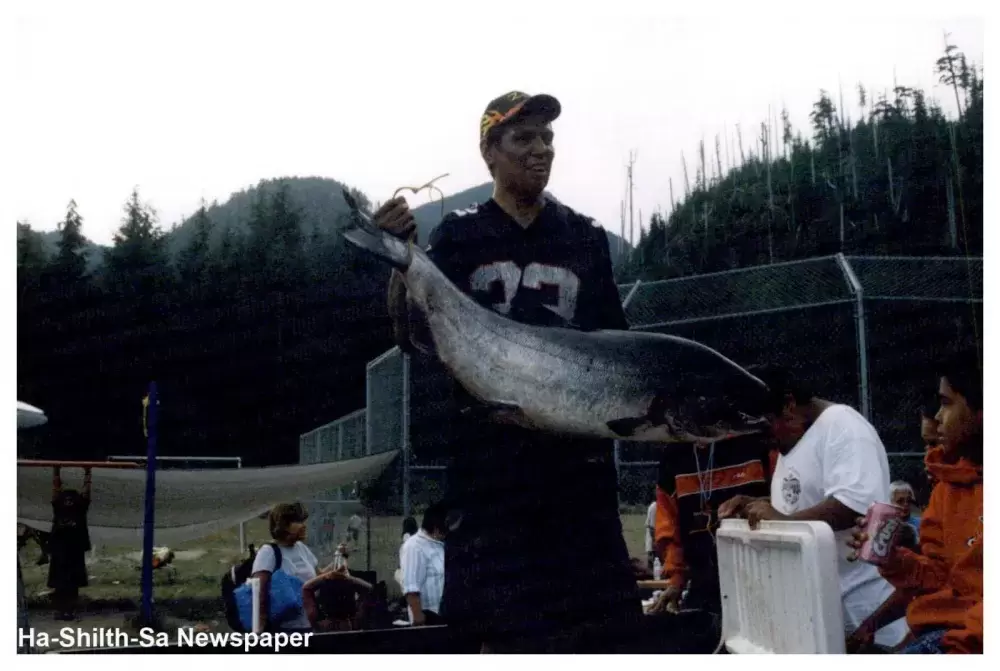

“Ahousaht harbor was filled with fishing boats, the mosquito fleet and even skiffs,” said Julia.

She recalled her late sister-in-law, Margaret Titian, would leave Ahousaht harbor in a skiff to go fishing off of the front beach.

“She got nine big smilies,” said Lucas. A smiley is a term fishermen use to describe exceptionally large salmon.

“Late Mary Amos did the same thing at Hesquiaht Harbour,” Julia recalled, saying Amos landed a few Chinook salmon in her skiff. “Fish did not go to waste – we ate it three times a day.”

Two out of 56 crab licenses

Today, Manson fishes through the court-won rights-based fishery, which allows him to fish “pretty much anything that bites the hook”. But he wishes to see more “brothers” out there.

“We’re only allowed a certain number of crab traps in Clayoquot Sound,” Manson noted.

He said there are 56 crab licenses in Clayoquot Sound and only two of those are Nuu-chah-nulth owned. Manson is tired of seeing licenses going to non-local, non-Indigenous large-scale commercial fishermen.

“Those guys don’t spend a dime here,” he said, adding that they come to make their money then go back to the mainland. “I’d like to see half the fleet being kou-uss.”

In order to survive as a fisherman, he needs to fish all species and he has to get creative when it comes to marketing.

“I have people willing to pay a fair or even better price than the local buyers,” said Manson, adding they are not a big operation but it’s enough to feed his family.

In the latest B.C. Court of Appeal ruling on Aboriginal Fishing Rights, which came out April 19, 2021, the court ruled that restrictions previously placed on how the five nations (Ahousaht, Ehattesaht, Hesquiaht, Mowachaht/Muchalaht and Tla-o-qui-aht) should harvest and sell seafood from their territorial waters be removed.

The courts determined that the nations have a right to a non-exclusive, multi-species, limited commercial fishery aimed at wide community participation, to be conducted in their court-defined area for fishing, which extends nine nautical miles offshore.

“This means that these nations have a right to participate in commercial fisheries for any species in their territory, and they don’t have to stay on the margins of those fisheries,” said Lisa Glowacki of Ratcliff LLP, lawyers for the Nuu-chah-nulth plaintiffs.

Proud of her late husband, Lucas said Simon put his whole life into fishing. He, along with other elected Hesquiaht chiefs, including Joe Tom Jr. and Stephen Charleson, supported the court case with monetary donations, said Julia.

“It was Si, George and Nelson that started it all,” she said. “Those three men really dedicated their lives to the court case.”

Both Simon and Nelson Keitlah were commercial fisherman and Nuu-chah-nulth leaders. George Watts was a prominent leader with the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council and Tseshaht First Nation. All men have since passed away.

But thanks to their efforts, and the work of those who followed, Stephen Charleson’s hope has been revived.

“I have hope again and am getting ready to go out again in my little boat,” he said.