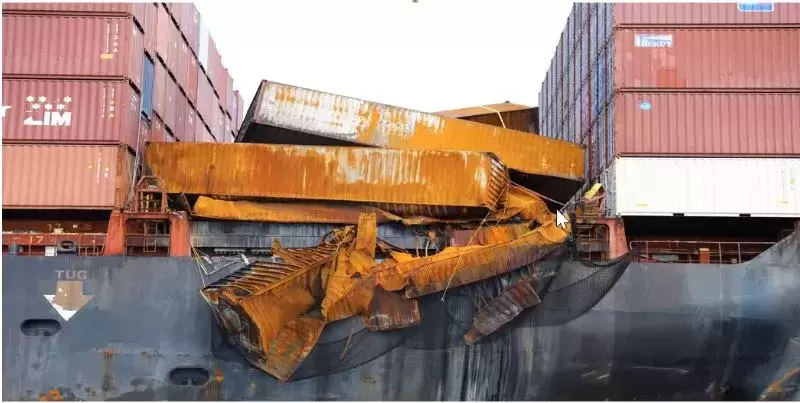

Over 100 shipping containers have been missing off the west coast of Vancouver Island since they fell off the Zim Kingston in late October, but in the coming weeks the ship’s owner plans to conduct a sonar scan to locate any of the wreckage remaining on the ocean floor.

This was reported by the Canadian Coast Guard in a recent update on the disaster, which began Oct. 21, 2021 when a fire started on the large shipping vessel as it approached the Strait of Juan de Fuca west of Victoria. Over the following days 109 of the 40-foot steel containers fell from the Zim Kinston, dropping a wide array of consumer goods into the ocean that would soon spread as far north as Haida Gwaii. Only four of the overboard containers were found Oct. 29 along Vancouver Island’s northwest coast.

The case is now being handled by the Canadian Coast Guard’s Vessels of Concern program, which gave an update on March 10. The program’s Acting Superintendent Gillian Oliver noted that the vessel’s owner, which is the Danaos Shipping Company from Greece, has so far been cooperative in attending to reports of unusual debris that have washed up since the Zim Kingston caught on fire. She said that last fall a thorough cleanup of four beaches in the Cape Scott area were paid for by the Greek company.

“They did 35 helicopter lifts, and 123 bags of garbage,” said Oliver, adding that other debris found on the shore of Haida Gwaii was reported to Danaos. “We didn’t realize it would go that far. But when it showed up and there was bags of shrimp chips and Yeti coolers they didn’t say, ‘We don’t think this is us, we’re not going to do anything about it’.”

By law, the company is responsible for material that came from the capsized containers, explained Oliver.

“According to our legislation, we have the ability to direct the owner to locate, mark and potentially remove containers if we are successful in finding them,” she said, adding that a search was conducted off the southern coast of Alaska. “The vessel owner also conducted a sonar scan of the Anchorage area around Constance Bank to determine that there were no man-made containers there.”

This spring a thorough sonar scan is planned where the containers were first reported to be missing, which is 38 nautical miles northwest of Ucluelet, the results of which will be shared with the public.

But the exact contents of the containers remain a mystery – except to those who shipped and ordered them. This leaves some who are closely watching Vancouver Island’s west coast to wonder if they are still encountering contents from the Zim Kingston five months after the incident.

By December of last year Ray Williams was seeing unusually large chunks of Styrofoam wash up at his home in Yuquot, on the southern shore of Nootka Island. Now he’s encountering material like water bottles and baby powder packages.

“It’s unusual to see that kind of stuff come ashore,” said Williams. “I have a strong suspicion.”

The Coast Guard encourages people to report sightings of strange debris to 1-800-889-8852.

“If it’s not reported back to Coast Guard, we can’t ensure that the vessel owner is taking steps to clean that up,” said Oliver. “We work with the vessel owner to let them know, and they go out and connect with the reporting party and conduct clean up. That’s what happened in Haida Gwaii.”

Further south at Long Beach, Esowista resident Nicole Gervais found unusual debris, like toys and grey rubber mats, on the shore late last year. Material continues to wash up, but it’s become more typical of what she regularly collects from the area.

“I picked up a whole wheelbarrow full of debris two days ago, in about 500 feet of beach,” reported Gervais on March 11. “The polystyrene washed up in December has now been pushed by the December tides under the logs and into the bushes.”

Two of the missing containers that fell overboard have been identified to have hazardous material in them. A document that lists the general contents of the missing containers identifies these hazards as thiourea dioxide, a white bleaching compound used in the clothing industry to remove colour from natural fibres, and potassium amyl xanthate, a yellow powder used in mining to separate ores.

The Coast Guard consulted Environment Canada about the dangers of this industrial chemical.

“The long-term impact of that particular material, to the best of our knowledge, is not going to be a long-term hazard,” said Oliver. “It would have immediate effects - like if there was something around it right away when it came out it could definitely have deleterious impacts to the environment - but the long-term impacts, it doesn’t sustain in the environment.”

Other shipping containers that went missing from the Zim Kingston are listed to contain consumer goods like furniture, toys and Christmas decorations. But legal issues prevent more thorough descriptions of what could emerge in the coming months and years.

“We don’t own that information, it’s private information between whoever bought the goods and who is shipping them over,” explained Oliver. “They don’t have the right to make that public.”

During the Coast Guard’s update Jerry Jack, a hereditary chief with the Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation, expressed his appreciation to how the federal agency has dealt with the Zim Kingston incident.

“I have all the confidence in your organization,” said Chief Jack. “The Coast Guard is miles ahead of any organization in working with First Nations people.”

Meanwhile, others remain frustrated for being left out of the immediate response effort. Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council President Judith Sayers said the incident revealed the need for better communication protocols with First Nations.

“At the very beginning, after the incident, we weren’t really being involved,” she said. “We had a meeting with the Coast Guard and we made sure that we were on their list.”

Sayers stressed the need for Nuu-chah-nulth observers as future sonar scans are conducted in the First Nations’ territorial waters.

“There’s still a lot more cooperation and information that we need. This is directly affecting our fisheries,” she said. “I really think they could be working more with our communities to be finding out any kind of traditional knowledge, the currents, anything that’s important in the waters.”

“You just don’t know the total impact on the environment until we find out what’s down there,” added Sayers.