On the first day of court proceedings in a case over aboriginal fishing rights, Nuu-chah-nulth leaders and their region’s MP are calling on Justin Trudeau to honour his commitment to Canada’s Indigenous peoples.

Today marks the first of five scheduled days for the B.C. Court of Appeal to hear arguments concerning the scope of how five Nuu-chah-nulth nations can harvest and sell fish from their territorial waters. The appeal is another chapter in the case over how Canada will accomodate the aboriginal rights of the Ahousaht, Ehattesaht/Chinekint, Hesquiaht, Tla-o-qui-aht and Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nations, which manage the T’aaq-wiihak fisheries on the west coast of Vancouver Island.

In 2009 the Supreme Court of Canada declared that the five nations have an aboriginal right to harvest and sell species from their waters. But in a highly sought-after region with declining fish stocks, how this right would be exercised has been caught in stalled negotiations and court appeals ever since.

Prime Minister Trudeau met with Nuu-chah-nulth leaders in Tofino in the summer of 2017, and almost a year ago in the House of Commons announced that Canada needs “to recognize and implement Indigenous rights.”

“We need to get to a place where Indigenous peoples in Canada are in control of their own destiny, making their own decisions about their future,” he said in February 2018.

“Trudeau’s in town today and if he thought reconciliation was the most important thing and his most important relationship, he’d be standing here with us today and telling us we’re going to resolve this,” said Judith Sayers, president of the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, while standing on the courthouse steps in Vancouver. “We’ve been fighting for our place in this country; reconciliation is about that right, that economic power and being back on the waters. I think that’s why all nations and putting their eyes on us.”

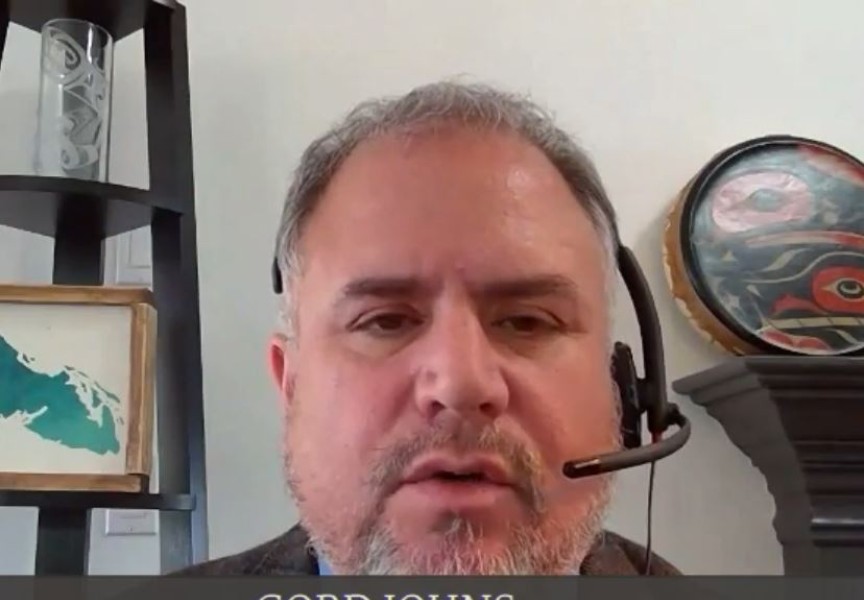

“Canadians should be horrified that their tax dollars are being used to hire government lawyers to fight Indigenous people in this country,” said Gord Johns, Member of Parliament for Courtenay-Alberni. “Governing is about choices and this prime minister promised that he would change the precedent in this country. Instead he’s chosen to follow the path of Stephen Harper.”

On April 19, 2018 the lead T’aaq-wiihak negotiators claimed a legal victory on the same courthouse steps after the B.C. Supreme Court ruled that the federal government had infringed on their aboriginal right to harvest and sell. But in her judgement Justice Mary Humphries also restricted the nations to “a small-scale, artisanal, local, multi-species fishery to be conducted within a nine-mile strip from the shore,” a narrowing of the scope of T’aaq-wiihak fisheries that led the five nations to appeal.

“They are now left with a shadow of the right described in 2009,” said Matthew Kirchner, legal counsel for the five nations, in his opening argument before the appeal’s three judges.

Kirchner also stressed that it was within the last generation that DFO regulations forced the nations out of the commercial fishery, a role they had previously held throughout British Columbia’s development.

“As recent as the 1980s there was a flourishing Nuu-chah-nulth fishery,” said Kirchner before a packed courtroom. “It was their fishery that helped build this province in its infancy.”

In its factum document submitted to the court, Canada’s legal counsel cited the 2009 Supreme Court ruling, stating that the aboriginal right is “not unrestricted,” does not entail an industrial fishery and is “not to accumulate wealth.”

“[T]the description of a right designed to sustain the community through the harvest and sale of fish was not accepted by the first trial judge, and thus the right does not provide a guaranteed level of income, prosperity, or economic viability,” stated the document, stressing that Nuu-chah-nulth fisheries did not traditionally trade on an industrial scale for the purpose of accumulating wealth. “A low level of commercial activity is the appropriate quantitative parameter for the appellants’ modern rights.”

During the press conference before the court opened, Ahousaht’s lead negotiator Cliff Atleo referenced a 13-year war that his nation engaged in 200 years ago for the resource that has fed and sustained his people since time immemorial.

“Our tribe, we fought a war over salmon,” he said. “We won for that salmon. And here we are continuing to fight in this modern day for that way of life.”